Image by the author

Science of Chess (kinda?): Viih_Sou's 2. Ra3 and a modest research proposal

Take the 2. Ra3 Challenge! For Science!In my previous posts I've tried to follow a straightforward recipe of identifying some chess research that I think offers a chance to talk about important cognitive science ideas and also reveals some neat things about the game and the way we play it. That means I try to read carefully, think about what I want to write more carefully, and spend some quality time with my draft before I hit "Publish."

Friends, none of that today.

Instead, I am writing about a piece of chess drama that caught my eye and my attention because (1) I think it's really fascinating and (2) It led me to an idea I had about it that you might find interesting too. That bit of chess drama has to do with the extended Blitz match between GM Daniel Naroditsky and GM Viih_Sou.

If you don't know what I'm talking about, the gist is that over the course of ~70 Blitz games, Naroditsky faced off against Sou, who kept playing the same highly dubious-looking opening of 1.a4 e6, 2. Ra3? Bxa3 (see below) and also kept winning somehow.

It really doesn't look great, folks.

There is already a lot of discussion about this episode which you can peruse over at Reddit, or you can watch GothamChess' recent video summarizing the latest updates. A lot of that discussion has to do with determining for sure who Viih_Sou is (though a key development is GM Brandon Jacobson's post on Reddit identifying himself as Sou) and also the possibility that this was a case of engine-assisted play. I find that latter topic profoundly uninteresting, so read no further if you're looking for musings about how one detects such behavior, etc. and etc. Instead, what I find fascinating about this scenario is a question that I remember thinking about waaaay back when I was a young scholastic player (and would have been PApatzer instead of NDpatzer): How much does it help to take an opponent out of their prep?

A brief history of NDpatzer's chess career (pre-1994 or so)

Listen folks, I was not a good chess player when I was a kid. In particular, I was a lazy chess player in that I very, very much did not want to study. I didn't want to learn openings and I certainly didn't want to memorize stuff about endgames or patterns or any of the rest of it. To my way of thinking, chess was supposed to be a battle of wits and not a test of who had memorized more stuff. When I first started playing the game competitively, this was enough to carry the day and give me a chance to win the occasional local tournament. As I got older of course, I started encountering players my age (and younger!) who had studied all that stuff and as a result were much stronger than me. I swallowed my pride, signed up for a chess class through my local chess club (thanks for your patience, Mr Griffin!) and worked on memorizing a couple different openings until I stopped one night to take stock of things - What was I doing? I could be at the arcade, or reading a book, or watching (and making) ridiculous zombie movies with my friends and instead I was trying to commit chess moves to memory so I could...what?....reproduce them during a game better than another kid?

I didn't have a laptop back then, but otherwise this is more or less the face I made when trying to learn openings in my childhood. Photo by Thomas Park on Unsplash

I decided I was done. Not all at once or anything - I still played in a few tournaments here and there and hung out with my chess-playing friends for skittles games and such. What I decided was that I wasn't going to work on chess and I was only going to go as far as that took me. That turned out to be through about 8th grade or so, after which chess was a hobby I put aside until 30 years of distance and a global pandemic got me thinking about it again.

OK, BUT...what I have not mentioned yet was something I ended up doing in between that decision to stop working on chess and fully stepping back from competitive play. Picasso had his Blue Period, Miles Davis had his two Quintets, and NDpatzer had his Weird Gambit period. See, I knew other kids were learning and memorizing all this stuff and I found it kind of irritating. So what did I do? I reveled in attemtps to take them out of book as quickly as I could. Oh, you like the Sicilian? How do you feel about the Wing Gambit? You like shooting for the Fried Liver? Let's see what you do with the Ulvestad Variation. Everyone knows some 1. e4 stuff, but how do you feel about 1. e3? I hadn't learned much about any of these lines, but neither had they. Like I said, it isn't that this took me very far in the world of competitive chess in southwest Pennsylvania, but I had at least a little more fun.

Prep and "playing some chess" both matter, but how much?

With just that little bit of context, I hope my interest in the Naroditsky/Sou games is understandable. Critically, what's super important to mention at this point is that Jacobson's post suggests that the reason Naroditsky kept losing is simple: Viih_Sou had workshopped that opening and Naroditsky hadn't! Here is my "Weird Gambit" approach writ large at the GM level! Besides being gratified to see my school-age strategem adopted by a titled player, now that I'm a grown-up cognitive scientist, this piece of the puzzle immediately got some research-oriented wheels turning. My first thoughts were as follows (I share them so you can see how a scientist thinks - in disjointed, possibly self-contradictory bulleted lists):

- This is so cool! It's almost a measure of how much losing your prep costs you in ELO.

- Wait, isn't Chess960 also just a measure of that too?

- No, that's not right - ELO's fundamental emphasis on predicting match outcomes means ordinal ability ranking is probably mostly retained (check to see if someone knows this?).

- Hang on - this is much cooler than Chess960: It shows you how much being way in your prep helps you when you're playing someone seriously out of theirs. You've got the patterns, but they need to solve problems.

- Can I measure that?

And this is where the possibly cool idea comes into play. I think that 2. Ra3? offers a neat opportunity to conduct an experiment that could allow us to quantify how much rating you gain from prepping something your opponent doesn't know at all. It's sort of a way of operationalizing the tradeoff between prep/patterns and more deliberative problem-solving. To paraphrase something IM Levy Rozman says in a number of his videos "Now you have to play chess..." once you run out of lines you know, but how does your latent ability to do that part of playing square off against something dubious that another player understands? My argument is that a truly weird (and objectively bad) opening like 2. Ra3? is the perfect way to ask this question because it probably leads one player squarely into territory they know well, while leading the other player straight into terra incognita. The outcome (with ELO ratings around to help) could provide a measurement of one kind of skill vs. the other.

My modest (research) proposal: The 2. Ra3 Challenge.

Alright - so let's get a little serious here. If we really want to try and use this as a means of measuring prep vs. more general chess playing skill, how should we do it? I suggest the following, though it's still half-baked (at best) and probably has a lot of problems with it that I haven't even thought of yet.

My idea is that we ask a whole bunch of players - including patzers like me, strong club players, and hopefully even a bunch of titled players of varying strength - to take the 2. Ra3? challenge.

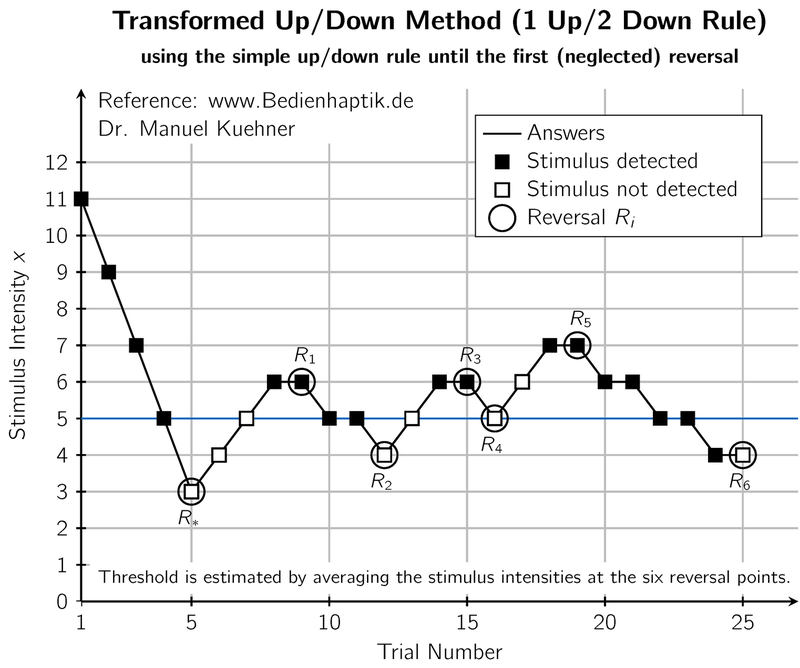

Here's how I want this to work - we'll use a strategy called an adaptive staircase to help us out. The big idea behind an adaptive staircase is that you're interested in finding a threshold of some kind, In my discipline, this is usually some kind of sensory threshold - how bright does a light need to be for you to detect it? How big a difference do you need between two images to reliably tell them apart? In visual psychophysics, we're often interested in these kinds of thresholds to measure the capabilities of different visual processes, and staircase methods are a means of measuring them fairly efficiently. The key idea is to begin by showing your observer a stimulus that is easy for them to detect, or a pair of images that is easy to distinguish. Presumably they will get respond to it correctly, after which you will make their life a little harder by making the stimulus harder to detect or your pair of images more difficult to tell apart. If they continue to get the answer right, you keep making it more difficult - if they get the answer wrong, however, you make it a little easier again. Once you arrive in the neighborhood of their threshold, they should alternate between getting correct answers and making wrong responses as you keep adjusting the stimulus above and below the level that they need to reliably do well. Once you see a few of those alternations, you can probably stop and calculate the threshold by seeing where the line was that they alternated around. You can see what that looks like in a typical experiment below.

A typical adaptive staircase outcome - the participant alternates right and wrong answers around a threshold value as the stimulus is adjusted according to their accuracy. ManuelKuehner (www.Bedienhaptik.de), CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

What I want to do is measure a threshold for beating 2. Ra3 as a function of your ELO. How strong a player do you have to be to beat this opening if the other person knows it really well? How does their ELO+weird_prep compare to your ELO with none?

One challenge with this design is finding the people who know this opening - as far as I know from the Reddit articles and the Gotham video, it's like two people.

BUT. But, but, but, my friends - we have a Hulk.

OK, not a Hulk, but an engine! An engine whose strength we can titrate, which means we can use an adaptive staircase!

Here's the recipe (and yes, it's another bulleted list - I told you, this is how I do):

- Find a player and record their ELO.

- Set up the 1. a4 e6, 2. Ra3 position.

- Assign Stockfish to play White at very low strength.

- Play!

- If the human wins, repeat 1-4 with the engine at a higher playing strength.

- If the human loses (or draws? maybe?), repeat 1-4 with the engine at a lower playing strength.

- After three alternations between winning and losing/drawing, average the approximate Stockfish ELO for those matches and call that the threshold for beating this opening.

I still need to think about this more, but I think it could be a ton of fun to see what happens! There are definitely problems with this design, but something like this might be a neat starting point for thinking about this as more than just a weird little bit of chess drama and more like an opportunity to go learn something about the game. I'm not exactly a viral chess sensation or anything, but if you like the idea and feel like seeing how you do in the 2. Ra3 Challenge, I would love to hear how it goes. Also, as always, please feel free to chime in the Forum with ideas about this situation, the idea for using this to try and study something about chess, or anything else you think is interesting to say about playing out-of-book, cognitive science, or whatever else is on your mind.

Back to more reasoned and carefully thought out posts soon, but I hope this was perhaps a little fun in its own right!

Support Science of Chess posts!

Thanks for reading! If you're enjoying these Science of Chess posts and would like to send a small donation my way ($1-$5), you can visit my Ko-fi page here: https://ko-fi.com/bjbalas - Never expected, but always appreciated!

References

None of these today - we're going straight off the top of my head.

More blog posts by NDpatzer

Science of Chess: Subliminal Chess in the Expert Mind?

Visual priming reveals how experts assess positions without awareness

Science of Chess: How does chess calculation depend on words vs. pictures?

Thinking ahead over the board requires maintaining some description of the position in your mind, bu…

Science of Chess: What happens in the brain when we see the best move?

EEG is good for measuring the timing of neural events, but can it reveal what happens when insight h…