Public Domain image edited by the author.

Science of Chess: How does chess calculation depend on words vs. pictures?

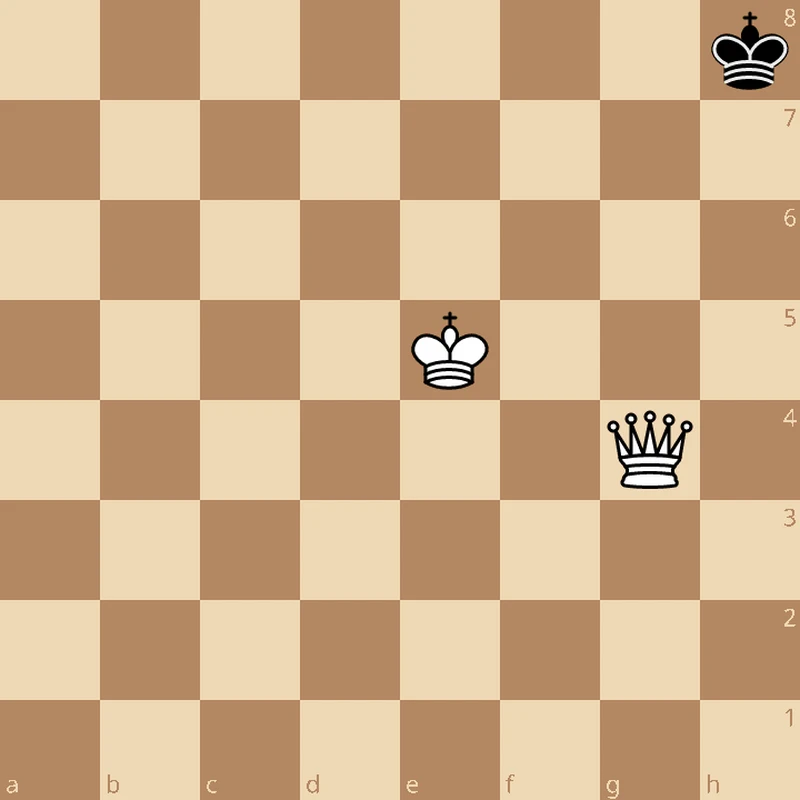

Thinking ahead over the board requires maintaining some description of the position in your mind, but what is the nature of that description?I have a puzzle for you. The good news is that it isn't very hard - I'll even tell you that it's a Mate-in-2 for White. The bad news is that I'm not going to let you see the position. Instead, you'll just have to do your best with the following description of the board:

White King on e5, White Queen on g4. Black King on h8.

...and here's a few blank rows to not spoil the experience! (the position is visible below).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Sure, you could open up a board editor and set this up, but I want you to try and solve it without doing so. While you're doing that, my real question isn't about whether or not you solve the puzzle but what your experience is of trying to do so. What are you thinking about? What's happening in your mind while you try to figure out the answer?

"Seeing" while blindfolded and imagining what's to come

This puzzle, by the way, is the first of Martin B. Justesen's 1160 Blindfold Chess Problems which is a wonderful e-book filled with increasingly challenging puzzles all to be solved without a board. I also won't keep you in suspense any longer in case you (like me) find blindfold problems very difficult. Here's the position I just described.

I'm guessing that this helps a lot. In case you really hate spoilers I won't post the answer here, but I'm confident that most readers will work it out very quickly. By contrast, I suspect that trying to think this through without a board to look at was quite challenging, even with this sparse position. Despite this apparent difficulty, many past and present chess players have demonstrated remarkable abilities to work through complex positions without looking at a board: Philidor (pictured in the thumbnail image), Alekhine, Morphy (pictured below) and a host of other famous players were (and are!) capable of winning multiple blindfold games in simultaneous exhibitions.

www.academicchess.org/.../morphy2.shtml, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Blindfold chess at this level is a particularly startling demonstration of an ability nearly all chess players try to use in normal play - keeping a position in mind and imagining what comes next. During a game, we all try to think through the consequences of candidate moves so we can decide whether particular next steps are good or bad. Like playing blindfold chess, this can be quite difficult. I tend to feel confident about calculating about two or three moves ahead, but beyond that I start to lose some kind of clarity about exactly what is where. This is an imperfect analogy, but it feels a little like the "Fog of War" variant in which some of the board is obscured during play.

Chess.com "Fog of War" example

A key part of my experience of trying to calculate is that I do feel like I'm picturing something, though. I describe my estimate of the board as "clear" vs. "foggy" because it seems like an image I either can or can't see very well. That's just my intuition, though - Is that really what my brain and my mind (or yours) are doing when I calculate?

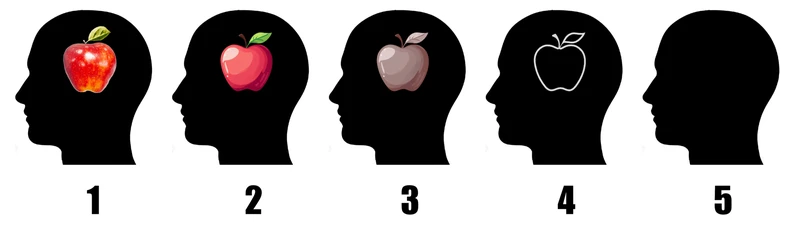

You might wonder what the alternative is - doesn't everyone have a mental picture they use when they try to think ahead OTB? The answer, which has become the focus of a lot of interesting visual cognition research lately, is no! Different people report very different experiences of visualizing things in the "mind's eye," with some individuals reporting no visual imagery at all. This condition is called aphantasia and is the extreme end of a spectrum of visual imagery that researchers usually assess with simple surveys.Below you can see an example of the kind of question researchers might ask participants to respond to on such a questionnaire: When you picture an apple, how vivid is that image you hold in your mind's eye? If you're interested in assessing your own imagery, you can try out the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) for yourself.

By Composition by Belbury, original image components by Mrr cartman, Caduser2003, Bernt Fransson and IconArchive.com - This file was derived from ilhuette.png:Apple 001.jpg:Äpplen 001.jpg:Red Apple Icon.png:, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=142324043

The VVIQ has important limitations, but I think it's fair to say that it provides meaingful evidence that visual imagery does indeed vary widely across different people. What does that potentially mean for how chess players try to maintain and transform a given position to evaluate their next moves?

Verbal and visuospatial modules in working memory

If you (like me) are someone who has the subjective experience of seeing a mental image of some sort when you imagine things, it probably seems difficult to consider what it's absence would be like. My experience of trying to calculate during a game makes it tough to understand what I would be doing if I didn't have a picture in mind. What is imagination without an image? To be clear here (and mindful of different people's experience), I want to emphasize that I don't mean that as a rhetorical question or to imply that varying vividness of imagery is a problem. Instead, it's a question about what that subjective experience is like. Individuals with aphantasia report using a lot of different strategies, but one I want to focus on is the use of verbal descriptions rather than pictorial descriptions. If you've ever watched Hikaru Nakamura calculate on his stream, you've certainly seen images like the one below, suggesting a highly pictorial (or at least spatial) representation of the board.

Arrows!

On the other hand, the same streams also often include him saying moves out loud in rapid sequence! "Nf3-g4-Nh5-Kh7-captures-captures-and-mate" for example, though please be aware that I just made that one up! That kind of quick description of a combination in words might be evidence of an equally strong verbal representation of the board that can be expressed in words or symbols. So here's the interesting question if you're someone who thinks about vision, cognitive science, and chess - what kind of imagination, verbal or pictorial, do players tend to rely on the most?

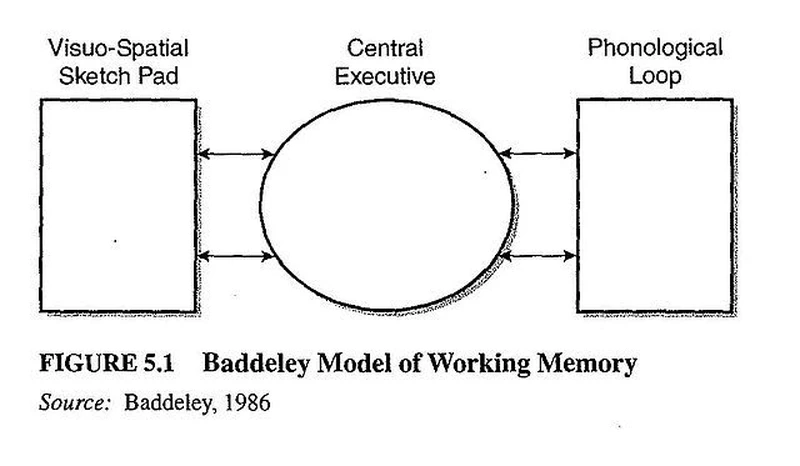

A classic model of human working memory (the kind of memory we use to keep information in mind for short periods of time) suggests people use a cognitive module we call the visuospatial sketchpad to keep track of pictorial and spatial information and a different module we call the phonological loop to keep track of verbal content. If you've ever tried to remember a 2AFC code or something similar for a few moments, you may have found yourself internally repeating the letters or numbers in the code so you wouldn't forget. That kind of phonological rehearsal is a process that memory researchers would attribute to the phonological loop. On the other hand, keeping a picture in mind or a sense of where things are in space during a brief interval would be attributed to the visuospatial sketchpad. Given that these modules appear to be meaningful to talk about cognitively, my question about verbal or pictorial approaches to representing and transforming a chess position turns into a question about specific cognitive processes. How are the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad engaged during play?

FrozenMan (talk) (Uploads), CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Using task interference to measure how modules contribute to complex tasks

This is a hard question to answer. The problem with trying to understand and measure someone's imagination is that it all happens inside the mind without obvious outward signs. There are some interesting candidates for objective measurements of imagery, but many of these have proven difficult to replicate and are thus hard to rely on. For example, there are some results suggesting that eye movements while "scanning" an internal image or pupil size while picturing a bright light may reflect the vividness of an individual's visual imagery. A number of these results have proven difficult to replicate however, so it pays to be careful. But in the absence of something like that, what do we do? Do we just ask people and hope that they have good insight into their own mental processes? Unfortunately, we can't just rely on that kind of introspection because metacognition (thinking about your own thinking) is also not guaranteed to be accurate.

There is, however, a clever way to estimate how verbal and pictorial imagination each contribute to a complex task like chess calculation. The big idea is to use task interference to measure how much one can interrupt the main process we're interested in (here ,chess calculation) by asking people to do something else at the same time. The logic behind this approach is that if the main task and the interfering task rely on the same processes and cognitive resources, it should be tough to do both at the same time. On the other hand, if they rely on different things, doing both shouldn't be so difficult.

This is the strategy reported in Saariluoma (1992), in which the researchers worked with 8 chess masters (average ELO over 2200) and 8 intermediate players (average ELO under 1750) to test how visuospatial and verbal interference affected chess calculation. The main task both groups were asked to complete was "Mate-in-1" detection: Given a position with White to move, can Black be checkmated on the next move? For half of the trials the answer was yes, while in the other half White would need 2 moves to win.

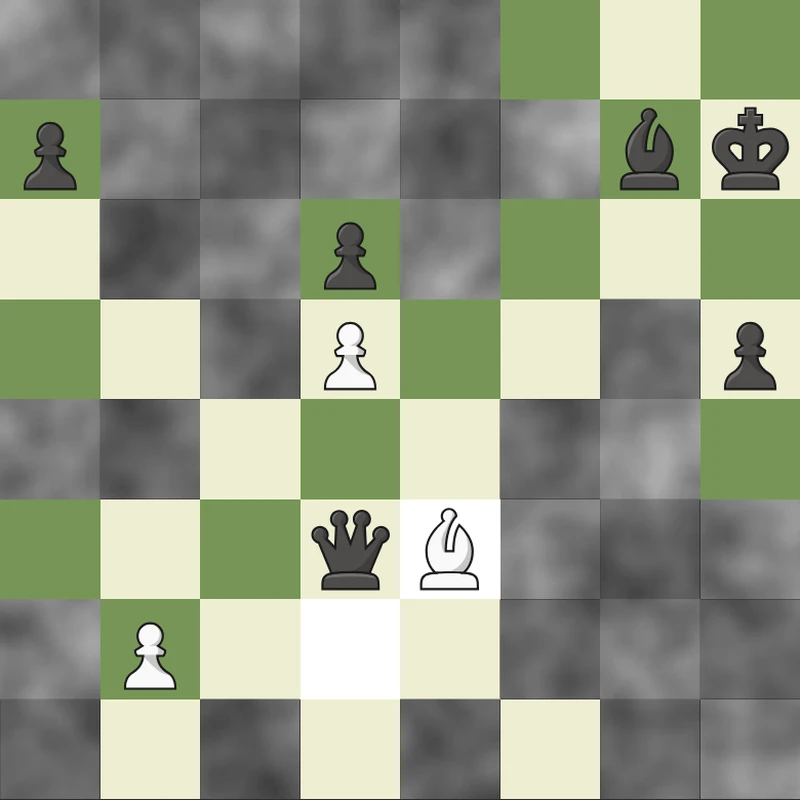

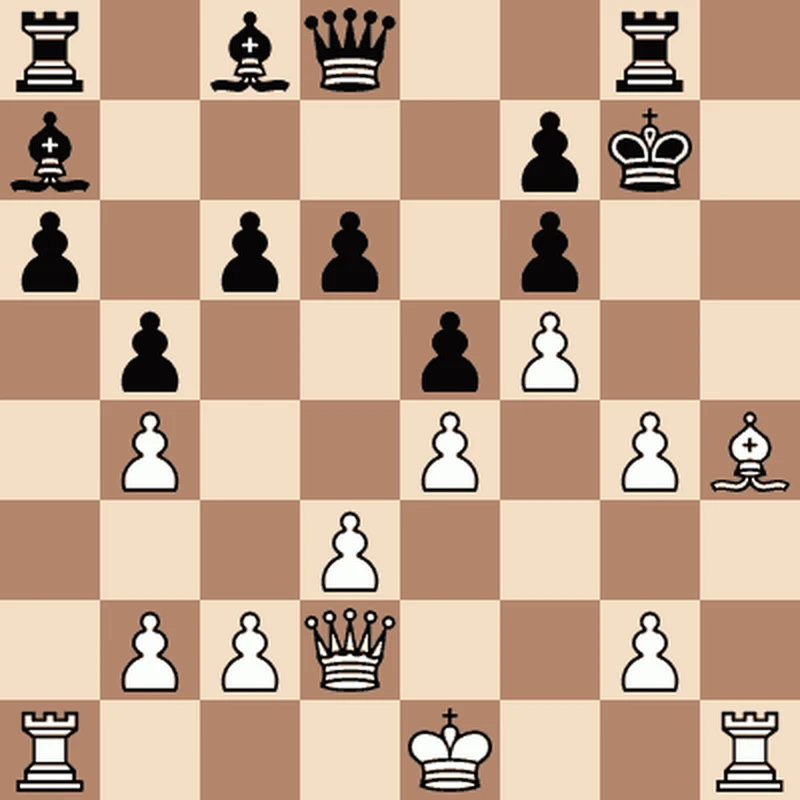

A trickier Mate-in-2 than those used in the target article. Jan.Kamenicek, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

But now here comes the interesting part: While players were trying to work these puzzles out, the experimenters asked them to do one of two secondary tasks at the same time. In their Verbal task, each player was asked to repeat a novel word over and over again (the word was TAIKURI) to occupy their phonological loop. In their Visual task, each player was asked to imagine tracing a path around the letters of the word TIIKERI and deciding if the turn they would have to take at each corner they arrived at was a left or right turn. This task was intended to occupy their visuospatial sketchpad. If this second visuospatial task sounds strange to you, I get it - however, this is a variant of an established neuropsychological assessment called the Money Road-Map test that has been successfully linked to visuospatial processing in the human parietal lobe.

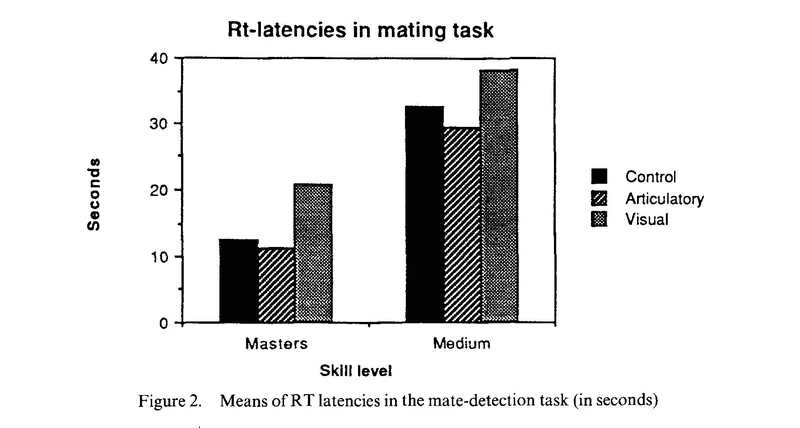

With these two tasks in hand, the critical idea is that if either of these interfering tasks makes solving Mate-in-1 puzzles harder, that's good evidence that you need that cognitive module (and presumably that kind of information about the board) to help you. You can see the results (graphed here as the time it took to answer the Mate-in-1 question correctly) depicted below. Because this is response latency data, a taller bar means that participants were slower and we assume that the task was more difficult. Shorter bars mean faster and we assume easier responses.

Figure 2 from Saariluoma (1992).

What these bars show you for the Masters (at left) and the Medium (or Intermediate) players at right is that repeating a word over and over again doesn't make you any slower to detect Mate-in-1. The black "Control" bar shows you the time it took to solve these mating puzzles with no secondary task interfering with you, so the hatched bar being about the same height as this one means this secondary verbal task didn't make the main task any tougher. However, the secondary visual task does interfere with both groups' speed! That dark-grey bar being higher than the other two in each case means occupying your visual imagination with another task made chess puzzle-solving harder. The conclusion is that even though verbal and auditory information seems like it could play a role in how you calculate and imagine a board, ultimately, chess appears to be more visuospatial. than verbal.

Next steps and further questions?

This is one of those results that may strike some readers as obvious - if chess seems very visual to you, you may wonder if the researchers had to go to all this trouble to test that idea this way. The thing is that this very easily could have turned out differently in ways that would have led us to different conclusions: Doing ANY kind of secondary task might have made the main chess task more difficult for example. That could either imply that players rely on both working memory modules to play or that chess is sufficiently demanding that any additional cognitive load makes things tougher to do over-the-board. You could also certainly have had verbal interference incur more of a cost than spatial. Because introspection and metacognition aren't perfect, doing tasks like this to check our intuitions is important for getting more evidence about how different mental processes contribute to complex tasks.

That said, there are a lot of important limitations here that are worth considering. For one, this is a case where modern training about statistics makes this result look a lot less convincing - 8 participants per group is just not a fantastic number and I'd love to see this result replicated (and maybe extended) with larger samples. Also, while tasks like check-detection or Mate-in-1 puzzles are easier to implement in an experimental setting, I'd also like to see how these results play out with a more naturalistic version of playing chess. Finally, there are definitely different forms of visual and verbal interference that could be worth considering. Compared to just repeating a word over and over again,Speech Shadowing in particular can be quite demanding, Other kinds of verbal overshadowing are known to disrupt a range of processes, including visual tasks like facial recognition, which may mean another look at visual and verbal processes during chess play would be worth considering.

Something that I also think is an interesting question related to this topic has to do with training. To what extent can we improve our visual imagery? What are the most successful kinds of training to do so, if any? I'm about to embark on Aidan Rayner's suggested visualization training regimen at some point in the next few weeks, and I'm very curious to see what it's like and how well it helps me see a little more clearly through the fog of my own visualization. As always, there are remain a number of intriguing next steps to take from here, but this study is a neat way to see how we can try to peek "under the hood" with careful cognitive testing to understand how the brain and the mind help us play the game.

Support Science of Chess posts!

Thanks for reading! If you're enjoying these Science of Chess posts and would like to send a small donation my way ($1-$5), you can visit my Ko-fi page here: https://ko-fi.com/bjbalas - Never expected, but always appreciated!

References

Baddeley A. (1992). Working memory. Science (New York, N.Y.), 255(5044), 556–559. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1736359

Marks D. F. (1973). Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures. British journal of psychology (London, England : 1953), 64(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1973.tb01322.x

McKelvie, S. J. (1995). The VVIQ as a psychometric test of individual differences in visual imagery vividness: A critical quantitative review and plea for direction. Journal of Mental Imagery, 19(3-4), 1–106.

Saariluoma, P. (1992). Visuospatial and articulatory interference in chess players' information intake. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 6(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350060105

Vingerhoets, G., Lannoo, E., & Bauwens, S. (1996). Analysis of the Money Road-Map Test performance in normal and brain-damaged subjects. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6177(95)00055-0

More blog posts by NDpatzer

Chess Engines, Centaur Chess and an idea for a new kind of tournament

Engines have had an enormous impact on chess - can we find ways to incorporate them into OTB play fa…

Science of Chess: Can you tell a human opponent from a machine?

Do chess engines pass the Turing Test?

Science of Chess: Subliminal Chess in the Expert Mind?

Visual priming reveals how experts assess positions without awareness