Finding Traps with Stockfish

Can an engine figure out if there is a trap in a position?When working with engines, one is usually trying to find out the objective truth about a position, so one usually wants to let the engines search to the highest depth possible. However, the objectively best lines don’t show any hidden traps in the position, which may be more relevant than the “truth” if one wants to understand a practical game.

In this post, I try to find traps in positions using Stockfish.

How to find traps

The general idea for finding traps is to look at how the evaluation of a move changes as the depth of the engine increases. If a move looks good at lower depths but turns out to be much worse at higher depths, there was probably some hidden resource that the other side had planned to refute the move.

To judge how much the evaluation of a move varies, I use my expected score formula rather than the standard centipawn evaluation, as the expected score differentiates between an evaluation drop from +4 to +3 and a drop from +1 to 0.

Let’s look at a first example to see how this works. Consider the following position from the game Vidmar-Teichmann, 1907:

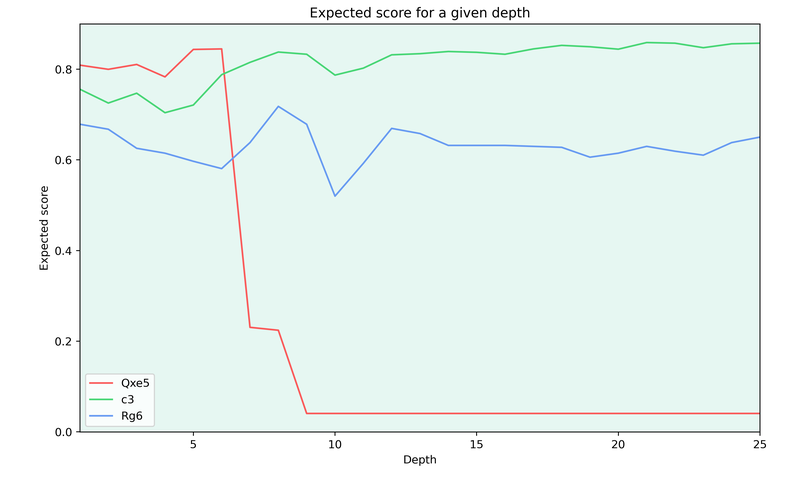

Black has sacrificed an exchange for a pawn and is standing very well. There are multiple strong moves, Stockfish prefers ...c3 and Teichmann played ...Rg6 which is also decent. But Black should certainly avoid 26...Qxe5?? 27.Qxh7+! Nxh7 28.Rd8+ Nf8 29.Rh8+ Kxh8 30.Rxf8#

As the e5-pawn seems to be hanging at first glance, Stockfish starts out wanting to take the pawn:

Until depth 6, taking the pawn is the top move before the engine spots the winning tactic for White. Humans and engines see the game quite differently, so comparing the search processes of the two is difficult, but I’d guess that moves that engines notice only at a higher depth are also more easily missed by humans.

Here is another example of a nice trap, this time in an endgame from Pilskalniece-Berzins, 1962.

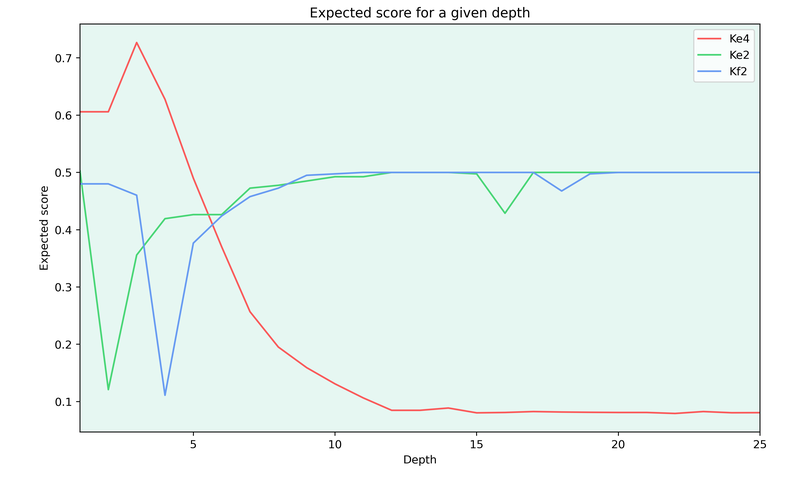

Black is a pawn up, but the position is objectively a draw. To try and get some chances, Black played 1...f4+!? with the idea that White’s most natural move runs into a trap: 2.Ke4?? Rd6! (preparing ...Ke6 and ...Rd4#) **3.Rxa7+ (**3.Rxd6 Kxd6 is just a winning pawn ending for Black) Ke6 and White can’t prevent mate on d4 without giving up their rook.

Here is how Stockfish saw White’s choices after 1...f4+:

At lower depths, Stockfish even thinks that 2.Ke4?? is by far White’s best option. Interestingly, Stockfish dislikes the other two moves early on, maybe because White’s king seems very passive. Note also that the dropoff for Ke4 isn’t as steep as in the previous example, which probably means that it isn’t immediately clear how bad the situation is.

Finally, let’s take a look at a stalemate trap, taken from the game Jansa-Rublevsky, 1992.

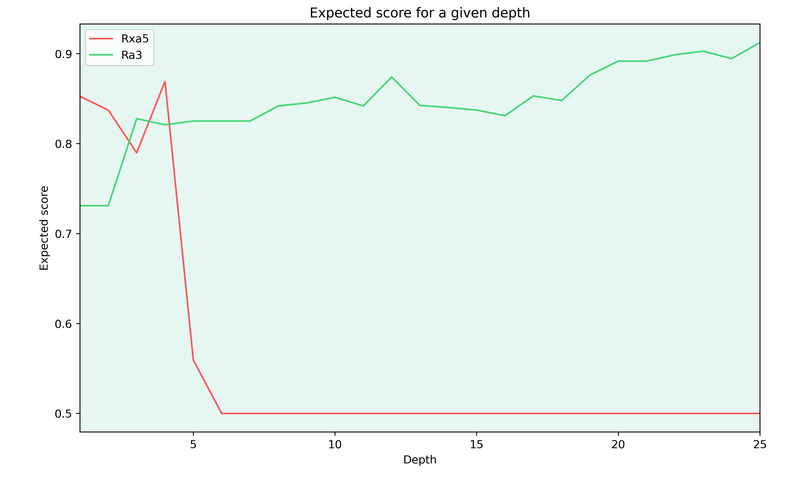

White’s position is hopeless as the a5-pawn isn’t going anywhere and the f3-pawn will soon fall. In the game, Jansa had one last trick up his sleeve, and it worked out: **1.Re2!? Rxa5?? (**Black should have played the rook to any other square on the a-file) 2.Ra2! Rxa2 stalemate.

Here is how Stockfish saw the different options for Black after 1.Re2:

At first, it thinks that it can take the pawn on a5, but at depth 5 it spots the stalemate after 2.Ra2.

Limitations

Missed examples

One thing I noticed is that this method doesn’t work to identify very simple threats. For example, positions where a hanging pawn can't be taken due to a fork. Usually, such traps aren't as interesting as most experienced players won't fall for them, but it's something to keep in mind.

I encountered a more interesting problem in the following position, taken from the game A. Petrosian-Hazai, 1970:

Black’s position is very bad as White will win the a5-pawn, so Black decided to lay a trap with the brilliant 45...Qb6!! and White took the bait with 46.Nxb6? After the moves 46...cxb6 47.h4 gxh4 48.Qd2 h3 49.gxh3 h4 the following position was reached:

It's clear that White can't break through, so the position is drawn. But Stockfish still thinks that this position is winning for White, so it doesn’t find the trap at all.

Technical limitations

An important part about setting up traps is that the wrong move has to be tempting, and that’s something I didn’t consider at all in the examples above. In general, it’s difficult to find out which moves “look human”. One try would be to say that tempting moves are moves that are best at some low depth, but this may also differ from human judgment.

Finally, I should add that I only looked at positions where the move that lays the trap has already been played, and then checked the opponent’s moves to see if any of them fall into a trap. Ideally, one would look for moves that lay traps before they have been played, but this would mean looking at every decent move (or, in bad positions, every move) a side has and then checking all possible responses. Theoretically, this would be possible, but it would dramatically increase the time it takes to find traps.

Final thoughts

I’m always a bit sceptical when trying to connect the human thought process to the search of engines, as they work very differently. But I think that this worked quite well for the traps.

While there are some limitations, I would think that an approach like this can help to highlight hidden ideas behind some moves. As I said, it would be even better if one could identify which moves seem especially tempting to make for humans.

Let me know what you think about this approach in general.

If you enjoyed this post, check out my previous post about finding ideal squares using Stockfish.

You may also like

ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… FM MathiCasa

FM MathiCasaChess Football: A Fun and Creative Variant

Where chess pieces become "players" and the traditional chessboard turns into a soccer field jk_182

jk_182How the World Cup Format impacts Results

Taking a look at all matches from previous world cups CM HanSchut

CM HanSchutLeela Chess Zero's spectacular Qxf5!!

It is all in the network! jk_182

jk_182Do Attacking Players play more Forcing Moves?

Finding forcing moves and looking through the games of world champions jk_182

jk_182