bymuratdeniz from pexels.com

Confirmation Bias - What is it, and how does it apply to chess?

Confirmation Bias is one of the more than a hundred cognitive biases that human brains are victims of. In this post, we will explore what it is exactly, and how it affects our chess performanceIntroduction

Human brains are flawed. Their capability for logical thinking is plagued by many cognitive biases, which influence how we make decisions and directly influence the quality of those decisions. Today, I will be looking at one of the biases that appear the most in chess thought processes - Confirmation Bias.

I will discuss the following questions:

- What is a cognitive bias?

- What is Confirmation Bias?

- How does Confirmation Bias influence our chess thought process?

- How can we mitigate the effect of this bias in our play?

What is a cognitive bias?

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking processes that change the evaluation of a presented situation in which a decision, which otherwise would be fully logical, becomes altered by the individual's flawed (biased) perception of reality. There are more than a hundred cognitive biases, but some of the most well known are the Sunken Cost Fallacy, which is the tendency for a person to stick with a decision even when the results from that decision are clearly negative, in order to not get the feeling that the previous invested resources (time, money, or others) were wasted, or the Gambler's Fallacy, in which a person believes that the outcome of a random event will be influenced by the outcome of one which precedes it (for example, while playing roulette in a casino, betting high on "red" because the five previous rolls landed on "black". Look up "Monte-Carlo August 18, 1913", where the ball fell on black 26 times in a row, causing players to lose millions because of the high bets on a "red" roll).

What is Confirmation Bias?

Before we delve in, lets play a little game: I will give you a sequence of 3 numbers, which will have some mathematical connection between them. Your task is to find what that mathematical relationship is, by giving me a sequence of any 3 numbers yourself, after which I tell you if they follow the same pattern or not. You may try as many times as you want, until you are confident you found the relationship.

Because we cannot actually communicate through this post because of space-time restrictions, I will simulate your replies.

Lets say that my sequence is 2, 4, 6. What relationship do you think these numbers have between them?

Now, I'll tell you that 8, 10, 12 also follow the same pattern. 16,18, 20 as well, as do 5, 7, 9.

Do you now know what the pattern is, or would you try more patterns?

If you thought that no further tests were needed because the rule is "increment by 2", you were a victim of Confirmation Bias, as the rule is actually " the numbers must be in ascending order".

Peter Wason and the 2-4-6 task

Peter Cathcart Wason was an English cognitive psychologist at University College in London and a pioneer of psychology of reasoning. Throughout his career, he designed many problems and tasks to test people for their reasoning flaws, and the "2-4-6 Puzzle", as it is sometimes called, is one of them.

Developed in 1960, this puzzle demonstrated Confirmation Bias in action. Most of his test subjects, when given the sequence "2,4,6", only tested positive examples of their initial hypothesis (for example, "increment by 2") instead of actively trying to refute it.

The results of this study further supported the notion of Confirmation Bias. Confirmation Bias is the tendency to seek and interpret new evidence that corroborates our existent beliefs, instead of actively searching for counterexamples to our hypotheses.

How does Confirmation Bias influence our chess thought process?

Now that we understand what this bias means, it becomes obvious how it affects our chess thinking. In the book Think Like A Super-GM, by GM Michael Adams and Philip Hurtado, the authors discuss this phenomenon, even though they do not explicitly mention Confirmation Bias. The book is about a set of exercises given to players ranging from 0 Elo to Adams, in which the players record their thought processes while solving the puzzles. In the results analysis, the authors discuss one of the key differences found between "club players" and "GMs" - while lower rated players tend to pursue an idea with an almost emotional attachment, trying to find a justification to play the first line they came up with (Confirmation Bias!), GMs tend to be more cold-hearted, and have the good habit of constantly trying to find the refutation of their own ideas.

Confirmation Bias makes us believe more strongly in what we think we already know. I have suffered from this many times. One example happened during Maia Chess Open 2023, in which I was playing the GM Stelios Halkias in the 8th round. The tournament was going well and, if I drew, I would likely get my second GM norm. I knew what I was doing in the opening up to a point in which he sacrificed a pawn. I took it, under the impression that it was a wrong sacrifice, and played some more natural moves. He started to think a lot, and I was enjoying my position a pawn up. I thought I might be much better. At some point, he got up, and went to the arbiter to tell her something... I have no idea what they briefly talked about, but my brain was so convinced that I was better, that I was reading all of his body language and actions as being nervous. During the game, I actually thought that he might be asking the arbiter if there was a 30 move rule for draw offers in effect, so he could try to offer me one!

The game continued though, shortly after he played a strong active move that I had not seen, and I finally understood he had full compensation for the pawn. Eventually, I blundered badly and lost.

How can we mitigate the effects of this bias in our play?

One question that I find helpful when we are choosing and calculating a line is:

What could be wrong with this line?

By having this question as the first thing that pops into our minds when choosing a line, we are immediately reminded to check for the opponent's potential annoying replies. We do not need to ask why the line works - we already subconsciously have a reason to want to play the move. However, many times, we forget that our initial intuition might just be totally wrong. This question has a follow-up question, which I find critical:

What will my opponent reply?

This question might seem basic and obvious, but you would be surprised (or maybe not!) at the amount of times I have asked this question to my students when discussing one of their games, and they do not have a clear answer. Their responses range from having a vague list of possible moves, to moves that do nothing to stop their ideas, either actively or defensively and are, therefore, not particularly good. How convenient!

In order to really improve our decision-making, we should have a clear response to this question. We must always know the best possible move for the opponent (to the best extent of our abilities), even if their position is not great. Think about this as putting yourself in your opponent's shoes and playing on his side for one move. If you play a move and do not expect a fighting move in return, your are setting yourself up for disaster.

Lets see some examples from my own games.

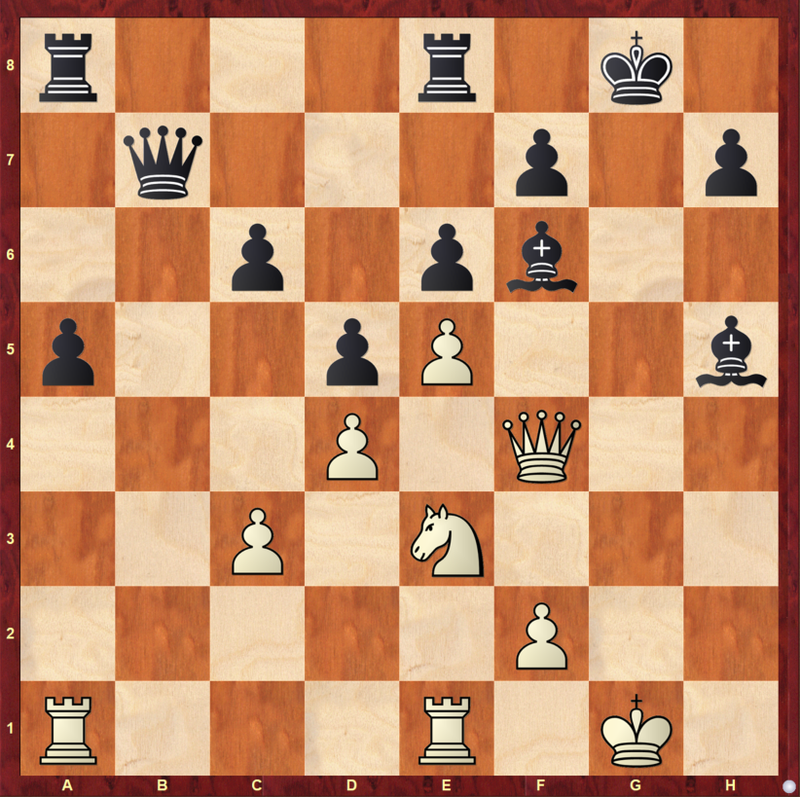

IM Sousa, A - Romano, L, Portuguese Cup 2025

In this position, Black had just played 26...Bxf6, capturing a bishop. How to take back?

I was under the impression that my attack was very strong and since the dark squares around the king were weakened, White was winning. I quickly played the horrible 27.exf6?? to which Black replied 27...Kh8! and had an almost winning position. Luckily, my opponent was low on time and I managed to turn the game around and win.

Black taking on f6 on move 26 just confirmed my assumption that Black was doomed. What did I expect Black to play after 27.exf6? Nothing, actually, as I just missed 27...Kh8 altogether (but I did not even look for it). Its over, I thought. This is something that you should never do. Never assume your opponent's best move is to resign immediately. Always try to find some way to continue, somehow, as you, in the same scenario, would never resign, but would rather try to keep up resistance.

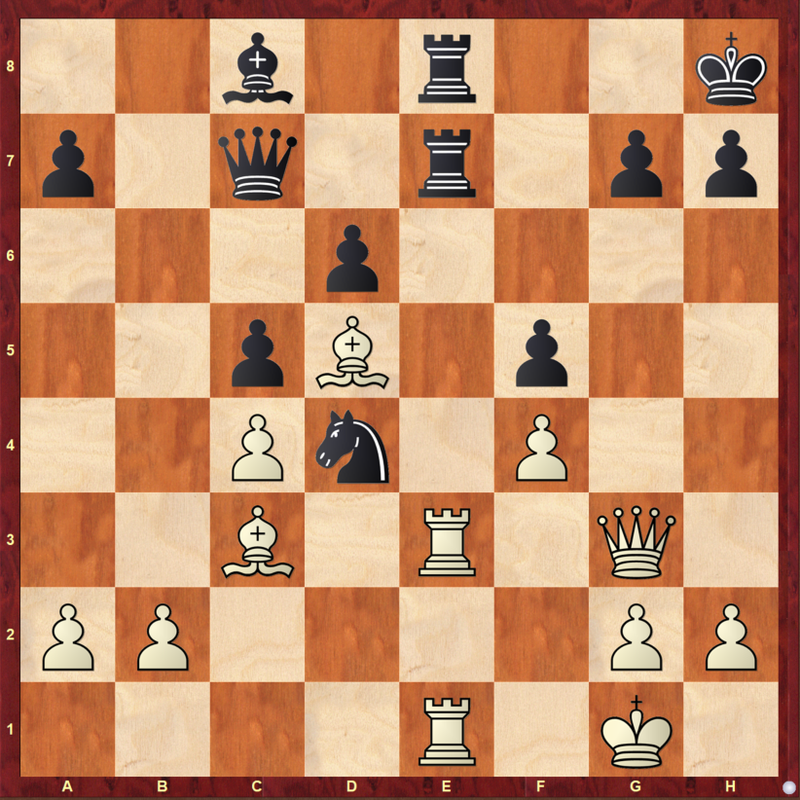

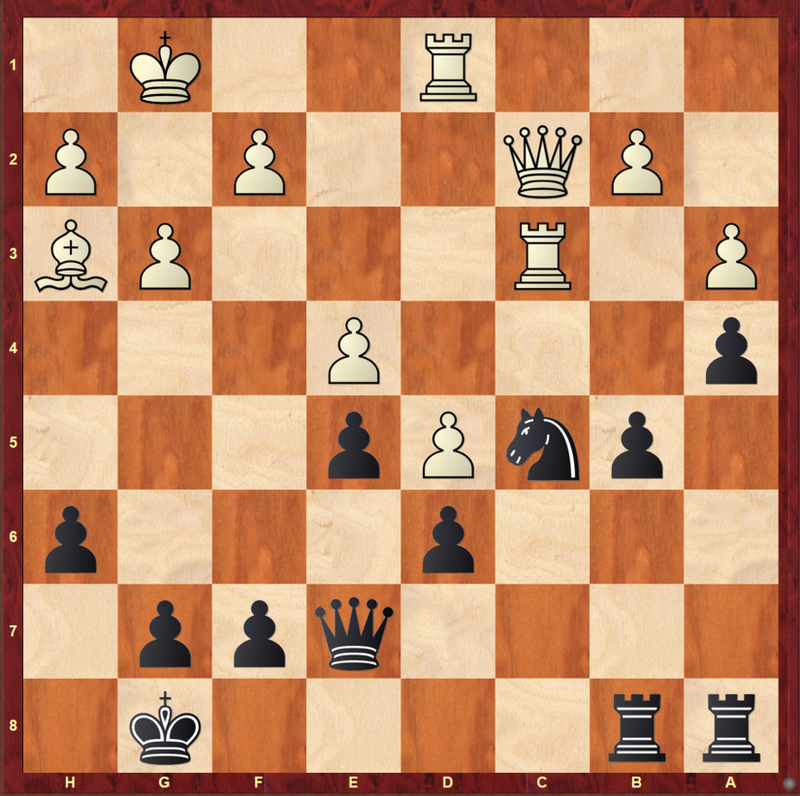

IM Sousa, A - FM Risting, E, Portugal Open 2020

Should you play 30.Qg6 in this position, with the threat of taking on e8? It just wins right?

If you ask yourself the questions "What could be wrong with this line?" and "***What will my opponent reply?***", perhaps you will find that 30.Qg6? does not win and is actually quite a bad move, on the account of 30...Nf3+!, neatly disrupting the precarious harmony of White's pieces which enabled the queen sacrifice. The game continued to an equal endgame in which I managed to outplay my opponent and win.

In the diagram position, once I saw the would be amazing 30.Qg6, I did try to find refutations to it, but they were really tame - for example, taking the queen, which would obviously be followed by mate immediately. I did not have a clear idea of what the opponent was going to play to continue - I just thought it was over. My emotional desire to play such a beautiful move was such that I subconsciously did not try very hard to refute it.

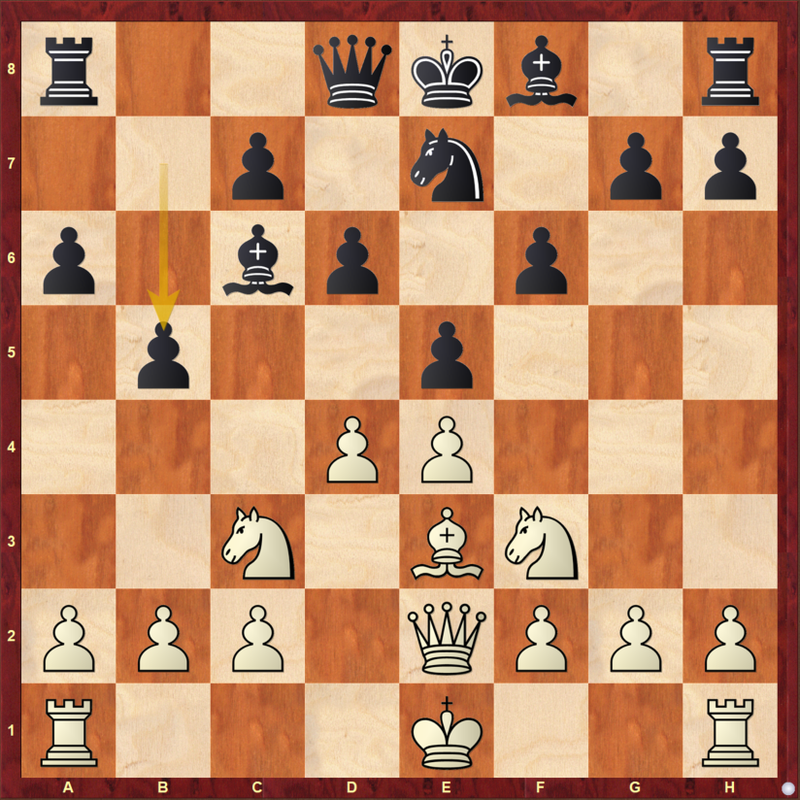

IM Sousa, A - Golecki, J, Figueira da Foz Open 2024

Should White play 10.0-0-0? I played so, quite quickly. I could not imagine that a move like 10...b4 would be good, given how Black was low on development. The game continued 10...b4 11.Nd5 Nxd5 12.exd5 Bb5 13.Qe1 a5

and here, I thought for 30 min and found absolutely nothing. Actually, Black is much better - bishop pair and good weakness on d5 to attack, besides the potential queenside attack. White cannot get any attack in before Black castles, which means that the long-term elements of the position will prevail. I ended up losing badly.

What went wrong on move 10? Clearly, the fact that I had an assumption of the evaluation of the position that was simply wrong, and I did not even fathom the possibility of that being so! 10.0-0-0 made sense to me, that was my initial hypothesis. But if I had tried to think what was potentially wrong with it, I could have understood the position better and played the preferable 10.a3 instead.

Lets finally see an example where I navigated the position correctly!

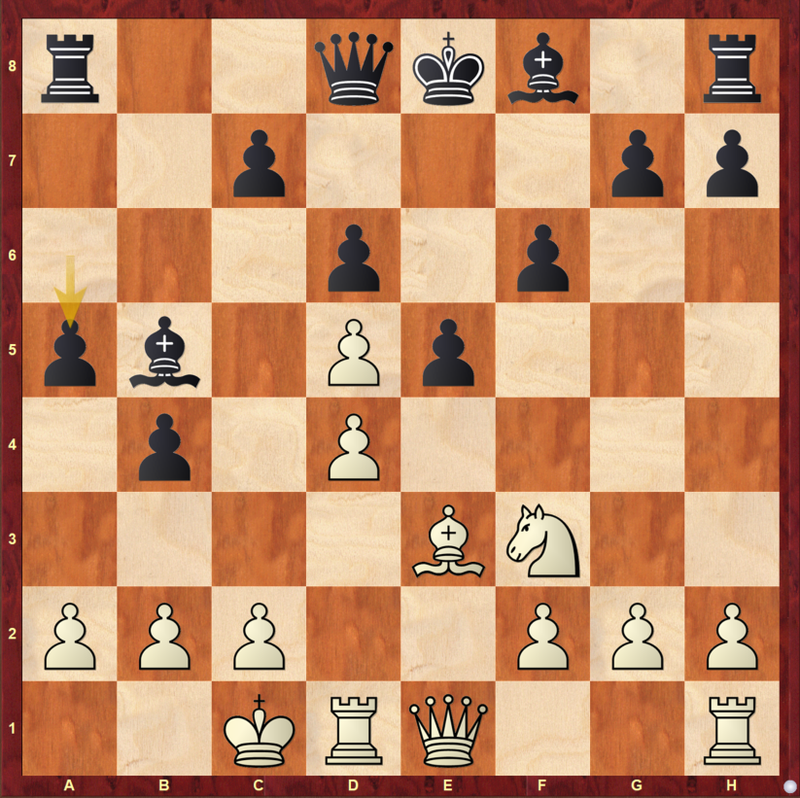

CM Leskova, S - IM Sousa, A, Roquetas Open 2025

Should Black continue with the plan 24...b4 increasing the pressure on the queenside?

It looks like an obvious move, but what could be wrong with it? What will the opponent try? White's position is depressing, so they will try to snatch every opportunity to complicate matters. That is why 25.Rxc5! would be very strong, when after 25...dxc5 26.d6 White has almost full compensation, very much different from the planless position they have on the diagram shown.

Seeing this, I played 24...Ra6 and went on to win the game without any problems.

Conclusion

We have discussed Confirmation Bias and we saw some examples of it in action. Now, you know the real effect this has in our chess performance, and hopefully you are more aware to this, and can work on trying to mitigate its effect on your play.

One thing that you might be thinking, and it is important to address, is my insistence that you should always have a response ready for the opponent and that you should not assume they will just give up. What if the position is actually winning and there is no defence? This is a valid question. Obviously, if we are to win any games, there will be positions in which there is no answer for the opponent. However, resigning is a decision that we typically take much more lightly for the opponent than for ourselves - and this is what we should remind ourselves of during the game. It is easy throw the towel when the pieces are not ours, but on the other side of the board, they will search for every check, capture, threat or defence, in order to stay in the fight. You should do the same, before you play. So, remember to always ask yourself what could be wrong with your move, and to always expect with clarity a concrete move for the opponent!

You may also like

IM HelloItsDmitri

IM HelloItsDmitriIs a rook on an open file a good piece?

Rooks on open files are not the full story when it comes to define whether a rook is well placed. In… IM HelloItsDmitri

IM HelloItsDmitriWhy are tactics critical for chess improvement at all levels?

Tatics are what win games at the beginnings of our chess journey. However, the stronger we get, the … ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… GM GABUZYAN_CHESSMOOD

GM GABUZYAN_CHESSMOODThe Rating Obsession: Why It’s Ruining Your Progress

Obsessing over rating is one of the biggest mistakes chess players make. In this article, GM Gabuzya… IM HelloItsDmitri

IM HelloItsDmitriHow should we play middlegames with opposite coloured bishops?

For many people, opposite coloured bishops mean that a draw is the likely outcome of the game. Lets … CM HGabor

CM HGabor