Why Winning in Chess is a Learning Opportunity

A Fresh Look on Game ReviewsThis newsletter goes out to +3,900 chess players on Substack. If you haven't joined yet, sign up now and get the ebook '100 Headachingly Hard Mate In Two Puzzles Composed By Sam Loyd' for free. You can sign up here:

saychess.substack.com

The other day I passed an interesting study on X (Twitter). It was an Israeli study on After-Event Reviews (AER) of soldiers’ navigation exercises.

I thought, hey, that resembles reviewing your games in chess. The study was performed by Shmuel Ellis and Inbar Davidi from Tel Aviv University. They challenge the conventional wisdom that learning from your mistakes is the essential way to improve. In chess, we often hear the mantra sounding something like “A lost game is a unique chance to learn, while a win is great because it is a win.” But is it true?

The study explores the concept of After-Event Reviews (AERs), a systematic approach to learning that involves analyzing both successes and failures. The premise is simple but powerful: while failures provide valuable lessons, so do successes, and ignoring them could mean missing out on key opportunities for growth.

The Study and Its Findings

The researchers conducted an experiment involving soldiers doing successive navigation exercises. These soldiers were divided into two groups. One group reviewed only their failed events, while the other reviewed both their failures and successes. The study found that the performance of soldiers who reviewed both types of events improved significantly compared to those who focused only on failures.

Initially, both groups had more detailed mental models for their failures—meaning they had a deeper understanding of why they failed than why they succeeded.

By working on reviewing the successes the one group managed to close this gap. This balanced view likely contributed to their faster improvement, as they could learn not just from what to avoid, but also from what to continue doing.

I think that it is something worth remembering in regard to chess learning.

Chess Analysis and Annotation

Chess players, particularly those playing in tournaments, are no strangers to post-game analysis. The common practice is to run the game through a chess engine, focusing on blunders, inaccuracies, and missed opportunities.

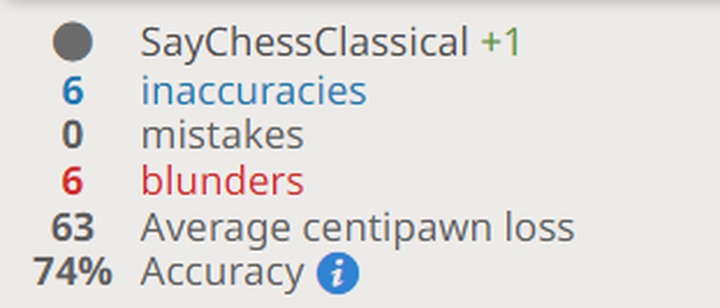

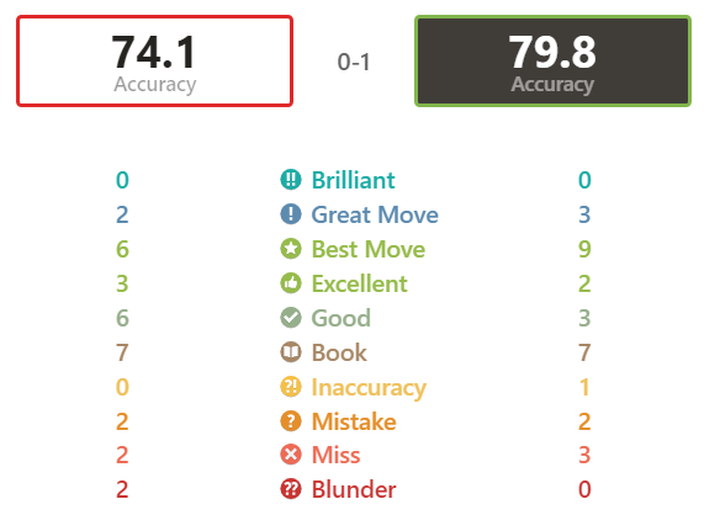

On Lichess you are presented with inaccuracies, mistakes, blunders, and average centipawn loss. All failures to play the objectively best engine move. Chess.com actually has a more balanced presentation including good, great, and brilliant moves.

The study's findings suggest that a one-sided approach of focusing only on mistakes might be limiting your growth as a player.

Imagine you just played a game where your opening play was perfect, leading to a strong middlegame that you later slightly misplayed in a muddy endgame. If you only focus on the mistakes you made in the endgame, you're missing out on the opportunity to reinforce the positive moves that led to your strong position in the first place.

By implementing the learnings from the study, you can start to balance this out. One thing worth trying is instead of just asking, "Where did I go wrong?" also ask, "What did I do right?" Analyze the successful strategies/moves you employed, the tactics you saw that your opponent missed, or the endgame techniques that you executed well.

At least, this is how I would interpret how the findings could be applied to chess training.

It would be interesting to set up a study similar to the Israeli study but for chess players. One group would only focus on learning from their mistakes, while the second group would spend equal amounts of time studying their mistakes and their good moves. Then see which group had improved the most after x-time.

While analyzing mistakes will always be crucial, maybe it's time we pivot toward learning from our successes too. Focusing more on successes might also make you enjoy your hobby more, while a heavy focus on mistakes could lead to a lack of self-belief.

You may also like

GM NoelStuder

GM NoelStuderHow To Get The Most out Of Our Beloved Lichess

You read this on Lichess. So you don't need to be reminded of this amazing platform. But do you real… FM CheckRaiseMate

FM CheckRaiseMateWhy Chess Books Don't Work

Books are the traditional way to pass on chess knowledge. How helpful are they really? SayChessClassical

SayChessClassicalAre Online Chess Players Trapped Pigeons?

The Increasing Gamification of Online Chess IM datajunkie

IM datajunkie#29: The 14 Rules of Hedgehog Club

Welcome to Hedgehog Club. The first rule of Hedgehog Club is: you do not talk about Hedgehog Club. GM Avetik_ChessMood

GM Avetik_ChessMood5 Crucial Steps to Stop Bad Results in Chess

Nobody likes to be in a bad chess period where you lose too many games. However, you can not only st… IM mmsanchezchess

IM mmsanchezchess