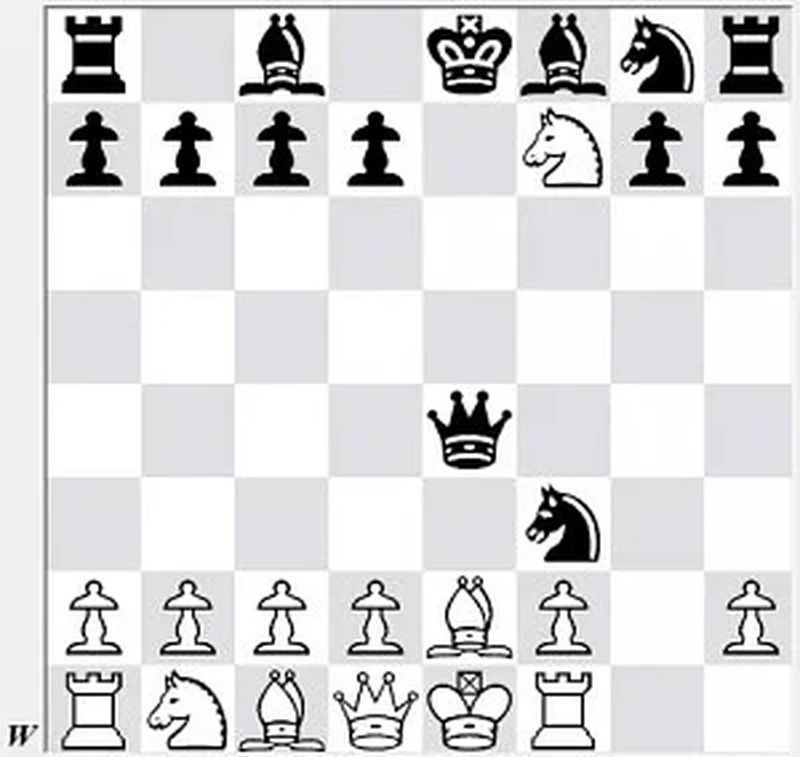

Image by NDpatzer

Science of Chess - How visual crowding can hide what's right in front of you.

The limits of your visual system can get in the way of reading board positions. Here's how.There are a lot of reasons why you might miss something on the board during a game of chess. Maybe you were distracted for some reason (I can and do blame my cat for a number of losses), or maybe you were so intently focused on a particular looming threat that you simply didn't take time to look anywhere else. Regardless of the cause, I'm guessing anyone who has played more than a handful games has had the experience of an opponent's piece seemingly emerging out of nowhere to do grievous harm to your chances. Of all the frustrating things that happen over the board, this is the one that leaves me feeling the most foolish I think: How on Earth did I miss that their bishop (friends, it's often a bishop) could just swoop in like that? Wasn't it just sitting there right in front of me? Chess is described as a game of perfect information because nothing is hidden from you or your opponent and there is no element of chance to the game, but clearly we all have some limits on the extent to which we take advantage of that perfection.

I swear, it came out of nowhere.

Because I'm a perceptual scientist, one idea I'm interested in is the possibility that expertise in chess, art, or other domains may affect the way you process visual information. To put it another way, do chess players, or artists, or baseball players actually see things differently? There are some simple answers to this question: Dr. Margaret Livingstone has published some interesting work comparing the eye alignment of artists as compared to baseball players with good batting averages, for example, which indicated that the athletes had eyes that lined up much better than the artists. Why should that be the case? Eye alignment is an important prerequisite for good stereo depth perception, which might be handy for assessing the approach of an incoming baseball. Conversely, some systematic errors in drawing and painting may be based on failures to effectively "flatten" the 3D world you're looking at onto a 2D surface. For artists, misaligned eyes may mean that they're side-stepping this problem by only needing to turn the "flatter" world they're seeing into a flat representation of the same scene on paper or canvas. The thing about these differences however is that they're not really about training or experience, but probably have more to do with a selection bias that plays out over the course of a lifetime. Someone with misaligned eyes is going to struggle to get hits in the batter's box, which makes it less likely that they'll climb the ranks to the major leagues after all. That means a result like this is a nice example of how individual differences in the way your senses work can lead to different outcomes, but what I'm interested in is how different experience and training may induce systematic differences in perceptual abilities.

One way to start thinking about this question (which is fairly broad) in the context of chess playing is to ask what the perceptual and cognitive limits on chess playing are. Our vision is good for a wide range of everyday activities, but are there ways that it tends to let us down when we're staring at a chessboard? Are there perceptual reasons why some things are literally hard to see during play? If so, when players spend a good fraction of their time playing, puzzling, and practicing different aspects of chess, do they end up transcending some of those limits so that they can literally see things that the rest of us can't? In this post, I want to introduce one key limit on our visual perception,visual crowding, that I have some experience thinking about from the academic side of things. I'll show you what crowding is, how it might make your life difficult over the board, and then say a little bit about something that might help mitigate it's impact.

When you think about the limits of your vision, one of the first things you probably think about is what we call visual acuity. This refers to your ability to see fine details, often defined in terms of the size of a pattern and the distance at which you view it. A Snellen Chart or similar collection of standardized shapes an eye chart like the one below (we use simple pictures of houses and apples and such for kids that visit our lab) is a quick way to determine how well an observer can detect the small differences in shape that make an R different from a P, or work out which way a Landolt C is pointing (see Michael Bach's excellent online widget for testing your own acuity if you're curious to see what you can do). If you, like me, go to the eye doctor annually to find out whether this is finally the year you need bifocals (not yet!) you probably have a good sense of what your acuity is in your central vision - that is, what you can see when you're looking right at something. This is part of the picture (quite literally) for sure, but it's far from the entire story. The rest of it has to do with, well, the rest of your visual field.

![By Fvasconcellos (talk · contribs) - Own work, afterFerris FL, Kassoff A, Bresnick GH, Bailey IL (1982). "New Visual Acuity Charts for Clinical Research". American Journal of Ophthalmology 94 (1): 91–96. DOI:10.1016/0002-9394(82)90197-0. ISSN 00029394.Ferris FL, Freidlin V, Kassoff A, Green SB, Milton RC (1993). "Relative Letter and Position Difficulty on Visual Acuity Charts from the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study". American Journal of Ophthalmology 116 (6): 735–740. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)73474-9. ISSN 00029394.Bailey IL, Lovie-Kitchin JE (2013). "Visual acuity testing. From the laboratory to the clinic". Vision Research 90: 2–9. DOI:10.1016/j.visres.2013.05.004. ISSN 00426989.Sloan letters from [1] (public domain)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98733617](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/ETDRS_Chart_R.svg/800px-ETDRS_Chart_R.svg.png)

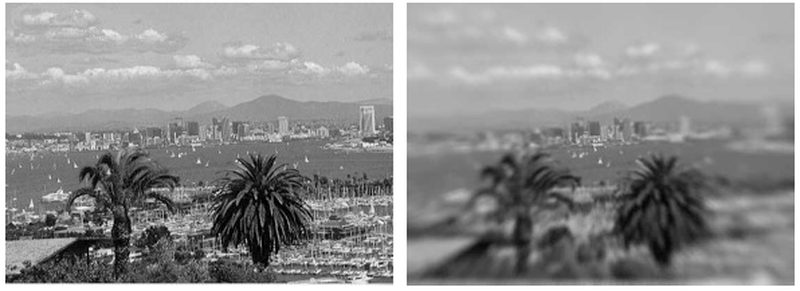

Whatever your acuity is in the center of your visual field, or what we call the fovea, it gets worse rapidly as you move towards the edges of your visual field. Just how much worse can be a bit startling if you haven't actually tested this, but trust me - it's pretty bad! You can see a rendition of how much your vision changes as you move from central vision outward in the image below. Besides having poorer acuity, your peripheral vision is also not as good for telling colors apart, or making a number of other basic visual judgments. What this means is that you can't get visual information about everything in your visual field that's all the same quality - whatever you're looking right at you can resolve clearly, but anything that's even a little bit off to the side might be harder to see and recognize because of these limitations. This is one simple way that you can miss stuff on a board: Poorer acuity might mean that you literally can't see the difference between the shape of a Bishop and the shape of a Pawn, making it all too easy to lose track of threats that are on one side of the board while you're looking at the center or the other side. The thing is that we're still not done - it gets even trickier than this, dear reader, because limited acuity is not the only problem with the periphery.

At left, a photograph of a scene - at right, the same scene rendered to approximate the acuity and contrast sensitivity limits of peripheral vision. Image Credit: Stuart Anstis

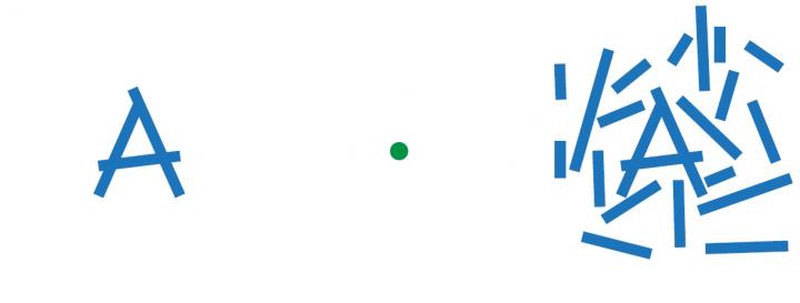

In the image below, keep your eyes on that green dot in the center and consider the letters off to the side. My guess is that the letter to the left looks a little blurry, but is nonetheless easily recognizable as a "A." But what about the letter in all that clutter on the right? That letter is the same distance from your fovea as the one on the left, so if the left-side letter was legible, this one should be as well. I'm betting you might find this more difficult to see, though - it's probably difficult to be sure exactly which lines go together to make a letter at all and which lines are just distracting elements. If you indeed found the central letter on the right more difficult to recognize than the isolated letter on the left, you were just a victim of the phenomenon known as visual crowding. Briefly, crowding occurs when an item is made harder to recognize due to the presence of neighboring items that are too close. How close is too close? It turns out that there is a systematic relationship named Bouma's Law that governs crowding - If you have an item that's a certain distance away from the center of your visual field (let's call that distance d), then stuff that's with d/2 units of the item will lead to crowding. That means things that are close to where you're looking are only made hard to recognize if things are right up against them, but things that are far away from where you're looking can crowded by items that are a decent distance away from them.

"Crowding" a letter A with some flanking lines. Acuity is matched, but crowding makes recognition harder. Image credit: Will Harrison

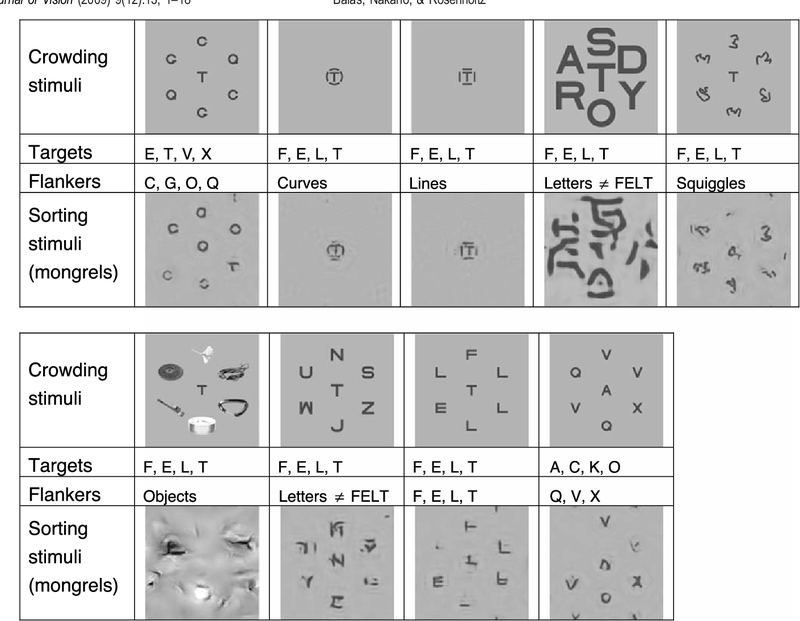

Remember, this isn't about your acuity! In fact, in some ways it's even more pernicious. Your visual system does a reasonable job of making guesses about what's really out in the world based on limited data, and by itself, blurry vision isn't so terrible to cope with. Crowding is something worse though, because it seems to involve your visual system sort of jumbling up the items that are crowded together and delivering a best guess about what was there using that mixed-up set of ingredients. My colleague Dr. Ruth Rosenholtz and I have worked with a particular model of this for several years now that allows us to make estimates of what those guesses might be, and you can see how hard to interpret they can be below.

A model of how visual crowding might jumble up visual structures.

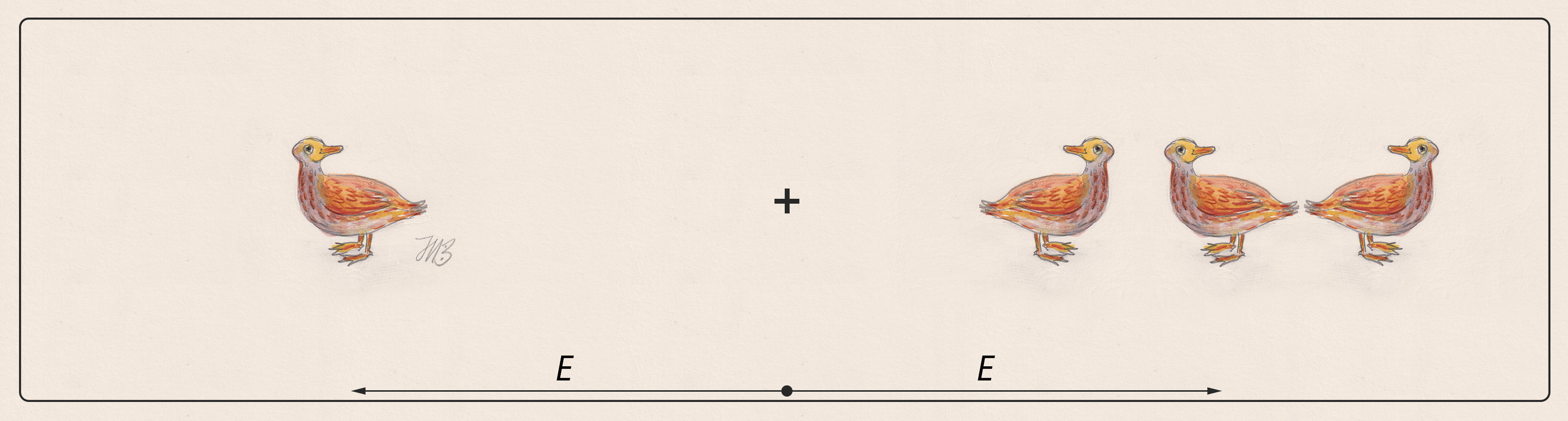

Remember that hypothetical Bishop hanging out in the corner of the board? That piece isn't just blurrier, it's also likely crowded by nearby pieces and thus getting mixed up with the nearby pawns, the king, anything that's inside that region defined by Bouma's Law. We know a good bit about how the shape of that pooling region (the area over which stuff gets mixed up) changes across the visual field, but again they key idea here is that you can't see everything at once. So how do you miss things that can happen over the board? By running smack into visual processes that jumble up edges, patterns, and shapes in your peripheral vision, but leave you with a guess about what is where that might be just enough off for you to arrive at the wrong plan. There is some neat evidence that the way information gets jumbled up might not be completely described by the kinds of texture-y estimates my colleague and I developed, but may instead involve something like the shuffling around of whole objects in your peripheral vision. That's intriguing from a vision science perspective of course, but deeply annoying when it means a brief glance at the board leaves you believing that a piece is on h6 instead of g7! To see what crowding is like when you have whole objects hanging out together in the same neighborhood (and to satisfy my Duck Chess aficionados out there), here's a lovely little example from Dr. Hans Strasburger.

Image credit: Hans Strasburger, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

What can you do about this? Hours of my childhood spent in front of the TV taught me that per G.I. Joe PSAs, "Knowing is half the battle," so one thing to say about this is that a reminder that you really do need to look around the board carefully. Your peripheral vision is great for a lot of things, but may systematically let you down under the conditions we impose by playing chess. Take matters into your own hands and use those extraocular muscles for something, folks - your rating may depend on it!

But back to one of the questions I raised at the beginning - is it possible that better chess players actually see the board differently? Specifically, could it be the case that these limitations on peripheral vision I've just outlined are less of a problem for players with a ton of expertise? I'm going to argue that the answer to this could be "yes," though I don't know this for a fact - I just think it's a neat hypothesis that might be worth looking into. See, even though visual crowding is pervasive and affects visual recognition profoundly there are some ways around it. One of these ways involves perceptual grouping, which broadly refers to our visual system's tendency to organize the things we see into larger chunks. If you look at the figure below, you'll see illustrations of the Gestalt Principles that correspond to some of the ways that we use properties like similar shape and color, spatial proximity, line continuation, and other aspects of visual appearance to group small items together into larger structures.

Image credit: Akermariano, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Several studies (many by Dr. Michael Herzog's laboratory) have demonstrated that this act of grouping may happen before visual crowding can exert its influence in some cases, meaning that chunking or organizing smaller items in your visual field into larger units may help make them somewhat immune to being crowded and jumbled together. My suggestion then, is that chess expertise may lead to better perceptual abilities to group pieces together into larger clumps - think of piece arrangements like a fianchettoed bishop above a castled king, or critical pawn chains in the Indian defenses. That ability to perceptually group pieces into big structures may mean that a board can be seen all at once by a chess master, or at least seen more accurately than a poor patzer like me can manage. This idea of chunking a board into super-structures like this isn't just my idea, incidentally, it's something Adriaan de Groot proposed to explain the superior mnemonic abilities of grandmasters for board positions (something I'll have more to say about in a later post). Whether that kind of organization is really happening at a perceptual level is unknown for now, but I'm very interested in the idea of perceptual training as part of a chess player's development as well as strategic and tactical practice.

So listen: Sometime soon, you will be playing a game and there will be a piece that darts across the board and does something you didn't anticipate. You can be mad, you can be frustrated, and you can curse the skies, the demons of your choice, or whatever chess gods you believe in. All I'm saying here is that in your frustration and anger, spare a moment to curse your visual system too, because it's almost certainly part of the problem.

Support Science of Chess posts!

Thanks for reading! If you're enjoying these Science of Chess posts and would like to send a small donation ($1-$5) my way, you can visit my Ko-fi page here: https://ko-fi.com/bjbalas - Never expected, but always appreciated!

You may also like

NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess - Problem Solving or Pattern Recognition?

We often say chess is a game of patterns, but here I look at a study that suggests it is also a game… NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess - Eyetracking, board vision, and expertise (Part 1 of 2)

Looking for the best move involves, well...looking. How do players move their eyes during a game and… NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess - Spatial Cognition and Calculation

How do spatial reasoning abilities impact chess performance? What is spatial cognition anyways? NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess: What does it mean to have a "chess personality?"

What kind of player are you? How do we tell? NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess: Seeing the board "holistically."

Better players may read a chessboard in the same ways we recognize faces. NDpatzer

NDpatzer