Trac Vu on Unspash

10,000 hours? Understanding the conditions for expert learning

An introduction to key ideas about the expert learning processWell, we need to ‘get good’. How are skills acquired? There is a paucity of expertise about skill acquisition in the chess world, and I have to admit I knew little about it. My friend Kabir Bubna is a performance coach in the esports space and is doing a PhD on skills acquisition. He kindly sent me a few articles to read that were quite eye-opening, so I am sharing some of the most important ideas that I learned.

Deliberate Practice

Ericsson’s theory of expert skills acquisition has made its way into popular culture through the books of Malcolm Gladwell. What people think Ericsson’s model is: the “ten thousand hour rule”. Do “deliberate practice” for ten thousand hours, and that’s how elite performers are made. This evokes the image of someone slogging with a timer and a tactics book. In fact, Ericsson’s model is far more interesting. Some decades ago, research in skills acquisition was done in a very narrow way: get some students to learn a new skill under laboratory conditions and run an experiment to see what works in learning. Ericsson thought this view of trying to understand learning and performance, focused on people being beginners at a task, was reductive and not insightful. He decided to reverse engineer the skill acquisition process of experts and try to understand how they got there.

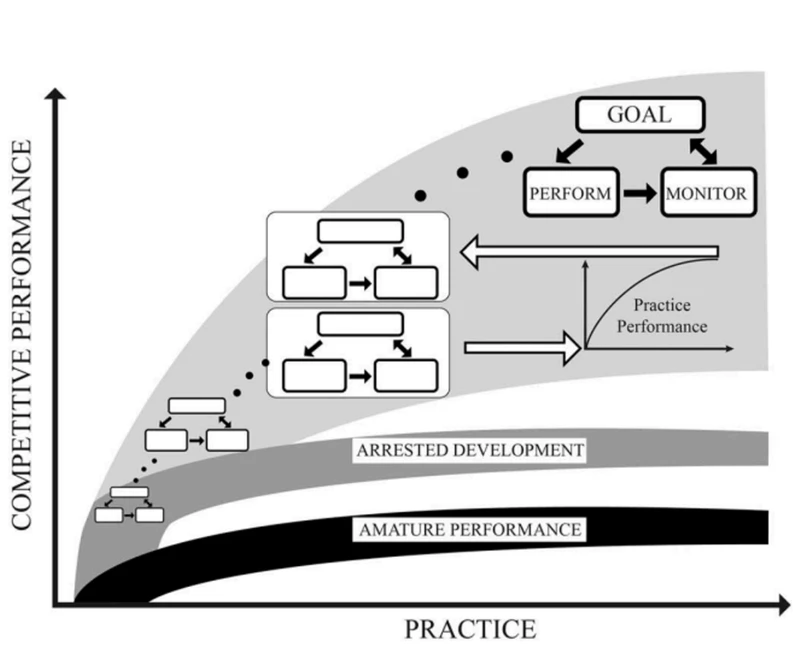

The model is the path of deliberate practice, with continuous change and re-evaluation of said practice as skills are growing. You don’t train the same way as a total beginner, the intermediate level or advanced level. What got you ‘here’ won’t necessarily get you ‘there’. Practice is called deliberate or purposeful because its explicit aim is to improve performance at the current state. Failure to adapt and tailor the practice to the current situation leads to stagnation and ‘arrested development’ (it’s only ten thousand hours Michael, how long can it take? Two months?).

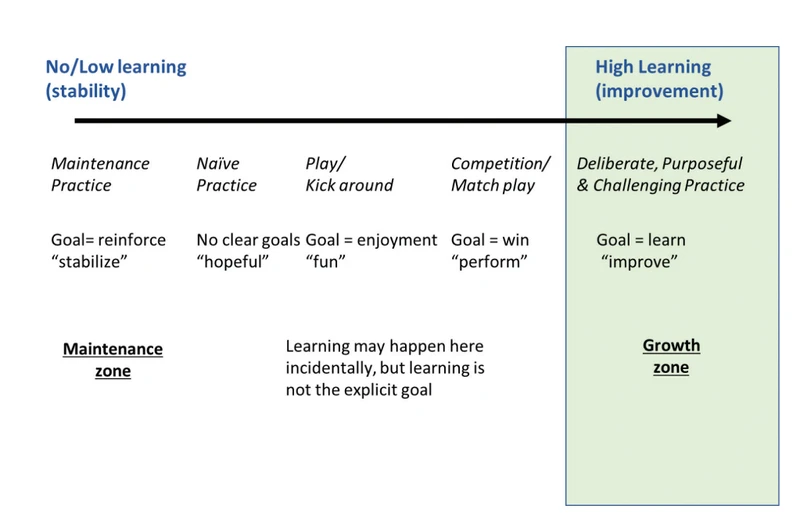

Deliberate practice is challenging and sometimes unfun, so it is impossible to spend a lot of time, let alone 10,000 hours, in this zone. In practice, some exercises will bring some fun, some will be for pure enjoyment, and some will be challenging, deliberate practice. We have a so-called continuum of practice:

If a player loves bullet but his growth zone is endgames studies, the bullet sessions will fall on the maintenance/naive practice of the spectrum, and the endgame studies will be the growth zone.

Coaches can play around on the continuum of learning to balance enjoyment and hard work if necessary. Of course, regularly spending enough time and effort in the growth zone is necessary for continuous improvement.

The Challenge point framework

Let’s introduce another very useful model, the Challenge point framework of Gauadgnoli and Lee (2004).

We define and differentiate two types of difficulty:

- Nominal difficulty: how challenging a task is on some absolute scale (whatever that is).

- Functional difficulty: how challenging a task is for a specific person.

So a mate that is elementary to most players can be of high functional difficulty to a very beginner.

A student's motivation level has to be managed: If they are constantly given problems of high functional difficulty, maybe this is great for the long-term, but they might drop out before getting there.

The specificity of the practice is important: is the practice specifically designed to improve competitive performance? I won’t venture too much into the territory of what you should do to improve at chess (not my expertise at all), but one should recognise the overall lack of training that is aimed at reproducing competition conditions, let alone making them more challenging. I’m a big proponent of the ‘long and difficult’ training session in view of tournament preparation.

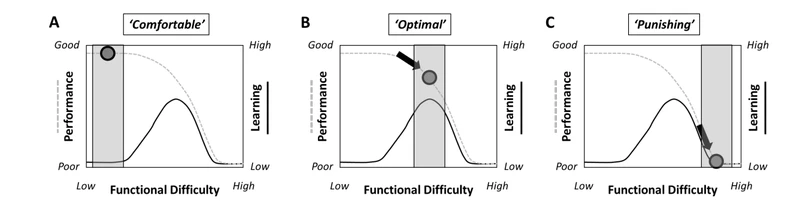

Let’s now introduce the challenge point framework as explained by Hodges & Lohse:

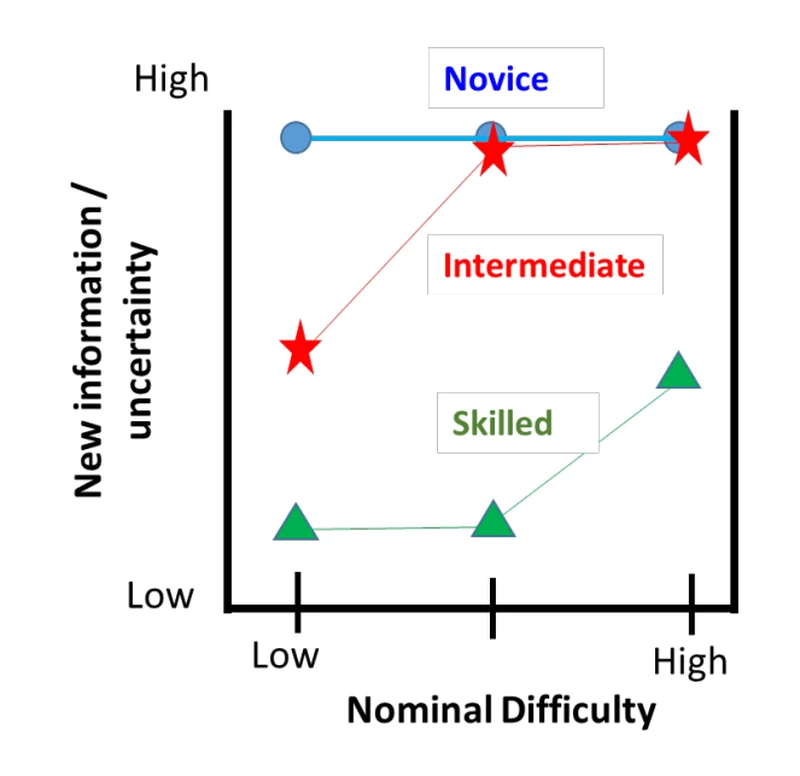

There are three basic principles related to the challenge point framework that can be used to design practice. The first is that new information (or a degree of uncertainty), is needed in practice for long term improvements in the current level of skill. In this way, learning is a problem-solving process where information is used to adapt behaviour and learn over the long term. The second principle is that an “optimal” level of difficulty or challenge is needed to get this information based on pre-existing capabilities. It is not merely new information but useable information that is needed. A learner's information processing capabilities limit the amount of potential information that is interpretable. Related to this last point, is the third principle, that an appropriate level of challenge is dependent on the athlete’s skill/experience and their information processing capacity relative to the demands of the task.

Importantly, there is some decrease in performance, but not too much that the challenge overburdens the learner. Conceptually at least, by adjusting the difficulty of practice, we can find the optimal place at which learning will be greatest. It is in this new zone where learning can now take place because of the availability of new, unexpected information. Before and after this place, challenge with respect to learning is sub-optimal, not difficult enough so that no new learning is taking place, or too difficult and overwhelming in terms of the demands on the athlete such that it is difficult for learning to take place.

For highly skilled readers (IM and beyond), you need a high level of nominal difficulty to stretch yourself (green triangles).

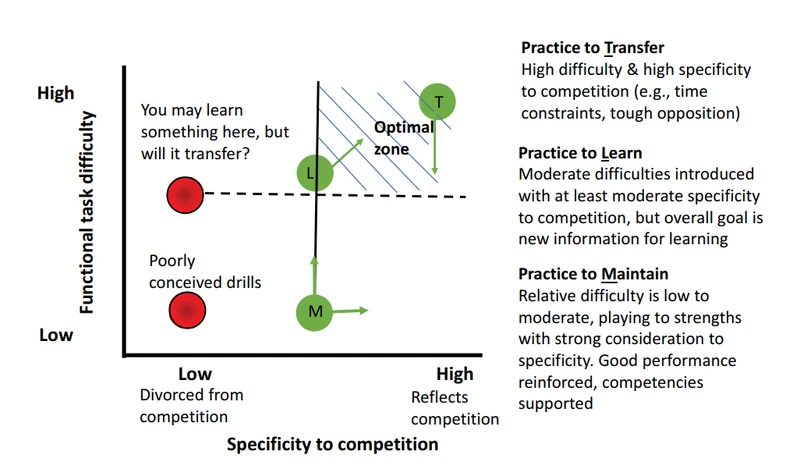

Three different “types” of practice:

- practicing to learn (forsaking short-term performance with the goal of long-term learning),

- practicing to transfer (maintaining high levels of difficulty and specificity to facilitate transfer of acquired skills to competition),

- practicing to maintain (reducing the difficulty to retain existing skills and growing athlete’s perceptions of their own competence).

We obtain the key chart where the specificity to competition and functional task difficulty can be used to map the different types of practices:

Let’s stop here and think about this chart in the context of chess practice. The first few puzzles of a 'puzzle storm' have low functional difficulty and medium relevance to competition: they are a typical ‘practice to maintain’. More challenging pattern recognition and calculation exercises are turning up the functional difficulty, while still being somehow disconnected from competition: they’re the typical practice to learn. Analysis of your own games, one key element of the so-called ‘Soviet’ school of chess, falls into the top right quadrant: it is highly relevant to competition: it’s a whole game and includes all the thinking processes and considerations made on the board. It is also of high functional difficulty because you stretch the analysis, calculation and evaluation beyond what you saw and did during the game.

It’s interesting to think of the top-left quadrant, which has high functional difficulty yet low relevance to competition. Maybe very deep and unnecessary opening preparation falls in there.

If you are a coach, what does that mean for your students? Let’s discuss a practical framework set up by Williams & Hodges [2023]:

SAFE – Skill Acquisition Framework for Excellence

Action point 1 – find the right balance in practice between focusing on long-term learning and short-term performance

This means a variation is essential: games analysis, calculation, etc. You need to manage all aspects, from maintenance to growth. I think most chess players won’t be mindful of the type of practice. Being quite deliberate in terms of what is maintenance and what is growth for yourself can be very beneficial.

Action point 2 – focus on the quality rather than merely the quantity of practice.

You won’t grow if you don’t challenge yourself, meaning if you always keep the functional difficulty low or average, you will have minimal improvement in skills. If you are highly skilled, it will be even more difficult: only functionally hard material will induce growth.

Action point 3 – create practice conditions that are specific to competition

evidence showing that athletes process information differently under high levels of anxiety, mental fatigue, and physical workload

If all your calculation exercises are ten minutes or less from time to time, how do you expect to carry the calculation effort of a whole game and still be fresh?

Action point 4 – consider individual differences in how learners respond to various interventions

Action point 5 – facilitate learning during practice rather than dictate or abdicate

coach to be viewed as a catalyst or a facilitator of change, rather than as a dictator of change

Action points 4 and 5 are standard and good coaching practices.

I hope that the above will be thought-provoking and help you to reflect on your own learning process and that of your students.

Many thanks to Kabir for proofreading the article. You can follow him here. All mistakes are mine.

You may also like

CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow to make your chess training effective

This is the first post of a series about effective chess training. In the following posts, I will di… BenjiPortheault

BenjiPortheaultThe War on Attention

I’m done consuming chess content IM theScot

IM theScotLife Hacks for Getting to IM

A post about the life-skills that help you in chess. CM HGabor

CM HGaborEffective training methods - doing tactics

My previous post was about chess training in general. We will dive into the details now. So, what yo… CM HGabor

CM HGaborEffective training methods - calculation training

A post about improving your calculation skills. BenjiPortheault

BenjiPortheault