FIDE Ratings Revisited

Do they offer the full picture, or can improvements still be made?0. Introduction

I revisit FIDE's recent rating changes and examine whether the Elo system still serves chess effectively. With data spanning March 2024 to June 2025, I show how global deflation, junior-driven volatility, and cross-federation mismatches expose systemic flaws. The system’s rigidity in a rapidly evolving chess landscape demands statistical modernization. Let’s unpack what the numbers reveal.

The assumed audience is comprised of chess hobbyists, tournament players, and FIDE stakeholders. Some basic math and stats will help, but no deep dives into formulas, I promise. If you want to skip ahead to a particular section, here’s the outline:

- A System Under Scrutiny

- Background: Floors, Adjustments, and Band-Aids

- The Numbers Tell the Story: Deflation is Real

- Global Activity: More Games, More Data, But Not Better Ratings

- Why Elo Breaks Down

- Conclusion: A Future-Proof Rating System?

1. A System Under Scrutiny

Last year, while the changes were still nascent, I explored the effects of FIDE’s new rating policies and the broader implications of the adjustments within the standard Elo framework. That article, ‘FIDE Rating Changes: Are They Working So Far?’, raised eyebrows and garnered 5 full pages of comments to go along with nearly 20,000 views on Lichess! Since then, the chess calendar has accelerated. New players are flooding in where federations invest in chess. Norm tournaments are increasing in places once considered off-the-radar, while European opens are becoming attractive for those who do not have the opportunities to face such a diverse array of high-rated players at home. All the while, FIDE’s rating system keeps churning out numbers rigidly and indifferently.

The FIDE rating system, built on the Elo formula, was revolutionary for its time. But in a chess world shaped by hyperactivity, global mobility, and asymmetrical tournament access, it's starting to buckle. This article re-examines how well the Elo framework serves the modern chess ecosystem and where it fails.

2. Background: Floors, Adjustments, and Band-Aids

When FIDE adopted Elo in 1970, chess ratings reflected a different world. The first published list in 1971 featured just 592 players, all rated above 2200. Fischer topped the list, and the assumption was simple: only serious, skilled players would seek FIDE ratings or qualify for them. This assumption shaped everything. The rating floor of 2200 wasn't arbitrary! It reflected the reality that casual players simply didn't participate in FIDE-rated events. The system worked because it served a homogeneous group with relatively similar competitive environments.

Then chess democratized. More tournaments, broader access, younger participants. The rating floor had to drop to accommodate this growth:

- 1993: Floor reduced to 2000

- 2010s: Down to 1000

- 2024: Raised back to 1400

Each change tried to balance inclusion with rating integrity, but created new problems. Lowering floors brought in weaker players and diluted the pool, shifting the entire distribution downwards artificially, not by a decrease in the chess skill.

The K-factor evolution tells a similar story. Originally conservative (K=15-25), the system became more volatile over time. Today's K=40 for new players reflects desperation to help ratings "catch up" faster, but creates instability when experienced players face newcomers. Meanwhile, FIDE kept accelerating publication frequency, from annual lists in the 1970s to monthly updates by 2012. More frequent updates meant more volatility and more opportunities for rating manipulation.

The 2024 reforms represent the latest band-aid: a one-time rating boost for sub-2000 players, restoration of the 400-point calculation cap, and a new initial rating method. Each change addresses symptoms while the underlying mismatch between Elo's assumptions and modern chess reality persists. The pattern is clear: reactive fixes to fundamental incompatibility. Elo assumed a stable and homogeneous player pool. Today's chess features massive participation, geographic diversity, and players ranging from casual hobbyists to world-class professionals, all in the same rating system.

The Rating Floor = Artificial Ceiling

Raising or lowering the rating floor doesn’t just affect beginners. It compresses the entire rating spectrum, squeezing out distinction and limiting upward mobility for ambitious players. While the rating floor changes managed to absorb more players into the system, it had a negative impact on those with higher aspirations for titles.

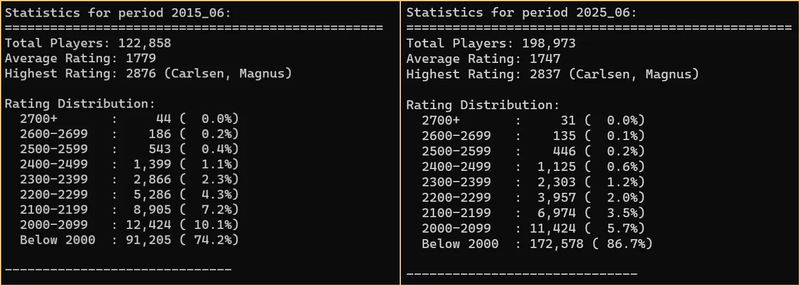

I found a gloomy reminder of that, and implicitly of my own title aspirations, last week while browsing the social media platform X. The user Gutsy Gambit posted the following screenshot, comparing active player distributions in June 2015 and June 2025 side-by-side. The comparison prompted me to explore deeper and write this follow-up.

Even as the number of active players has surged, ratings above 2000 Elo have steadily deflated - not from declining skill, but from systemic flaws. So, maybe instead of patching things up every few years, the time has come to rip off the band-aid?

3. The Numbers Tell the Story: Deflation is Real

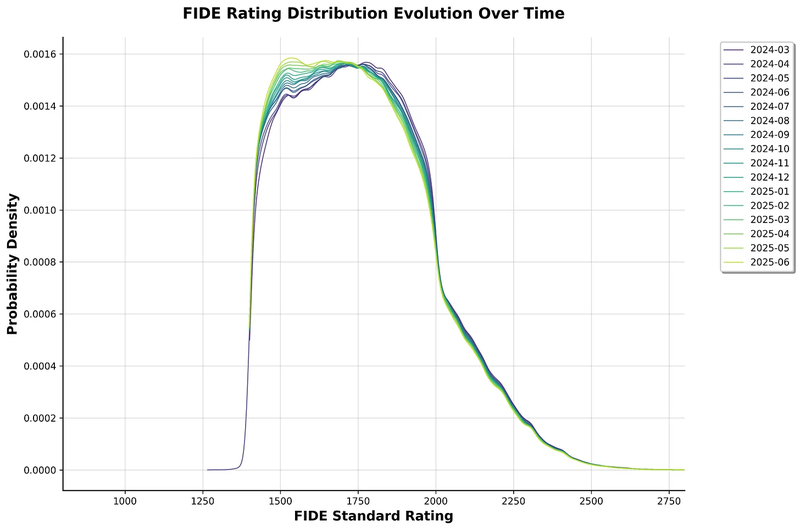

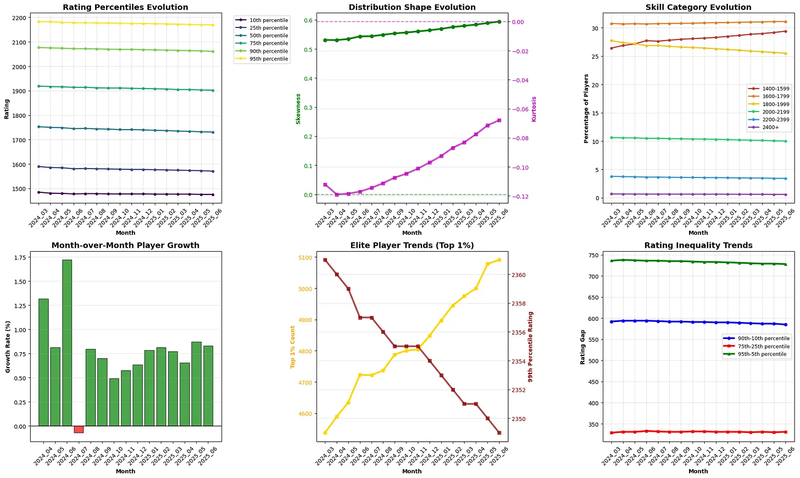

At the time of this writing (June 2025), here's what the rating distribution has done since March 2024:

Key trend: More and more players are clustering around the 1500 mark

Notice the pile-up at 1400: this is an artifact of the floor rule, not actual player skill.

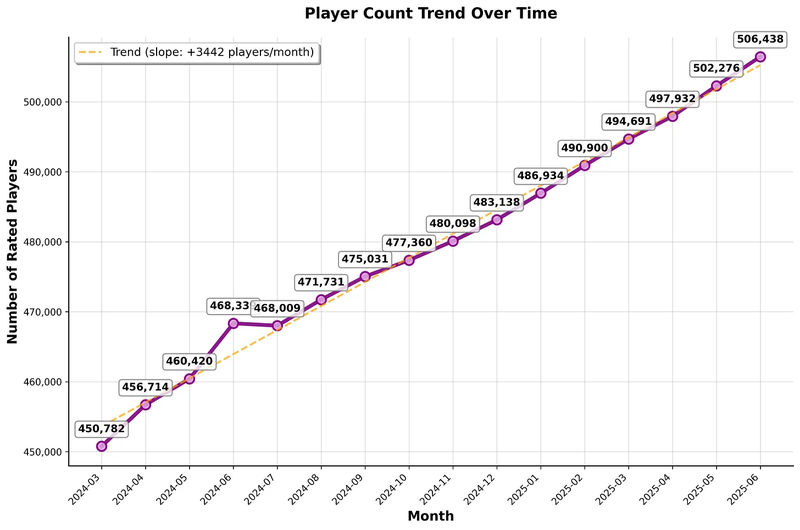

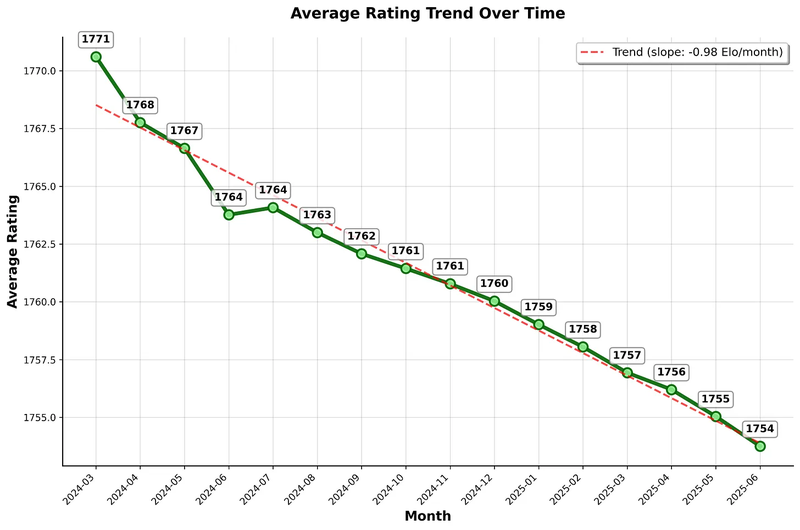

~3,500 new Standard-rated players are added per month, yet the average rating keeps declining.

The average rating is falling at ~1 Elo/month, despite growing participation.

Three patterns emerge from this data:

Universal deflation. Even elite players (top 1%) show declining ratings, indicating systematic issues rather than skill decline.

Distribution changes. The underlying distribution is becoming more skewed and with a sharper peak.

Demographic shift. Sub-1600 players now dominate the active population, fundamentally altering the rating ecosystem.

The 1800–1999 rating band is slowly being replaced by the 1400–1599 band

This isn't a performance decline, it's structural compression. The Elo system flattens complexity into simplicity, but in doing so, it also flattens its own validity. It reacts too slowly for fast-improving players, and too weakly to structural asymmetries such as geographic and economic disparities. And while it still works well for elite stability, the bulk of the chess ecosystem suffers from its rigidity. Aspiring players have bigger roadblocks in their way to the top, and casual players suffer from a system that is biased against them.

Over the past 20+ years, some of the measures taken by FIDE look like stopgap solutions, not comprehensive long-term fixes. In particular, among the top brass of FIDE, there’s a widespread belief that the Elo system is the only acceptable solution for players to be able to calculate their own requirements for scoring title norms. Although I don’t expect immediate action, I hope my points here are compelling enough to lead to some reflection and internal discussion. If I can be of any help in such discussions, I would gladly participate.

4. Global Activity: More Games, More Data, But Not Better Ratings

Renewed popularity of chess

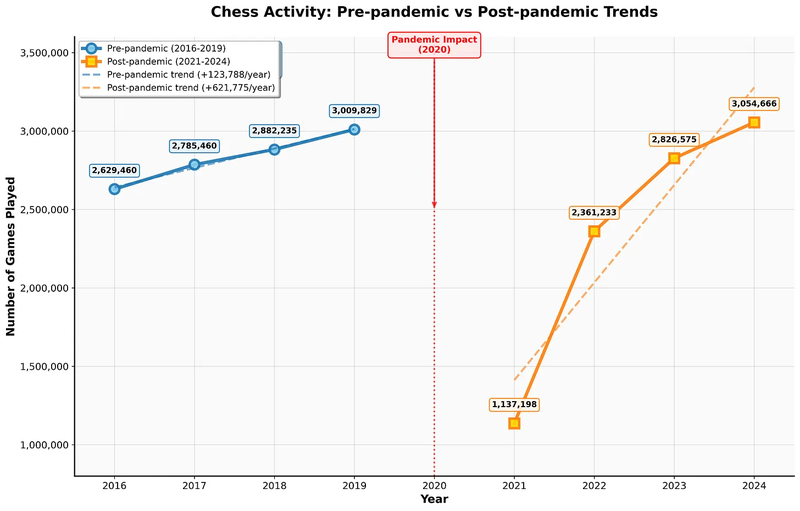

Three factors govern the surge in activity:

- Pandemic shutdowns and an increase in work-from-home

- The Netflix show The Queen’s Gambit

- More chess content on livestreaming platforms such as Twitch and YouTube

If we assume that 2021 was the first year OTB chess activity resumed in earnest, we can take a look at the number of games played in this interval, compare it to pre-pandemic levels, and also forecast some future growth. I have chosen to discard the 2020 year entirely from the visualization, as it’s a clear outlier, with a near-global chess shutdown.

Although the post-pandemic increasing trend is starting to flatten out a bit, we are still due to eclipse 3.5 million games by the end of 2025. The recovery has been nothing short of impressive, with 2024 being the most active year in history, which coincided with the FIDE centenary celebration.

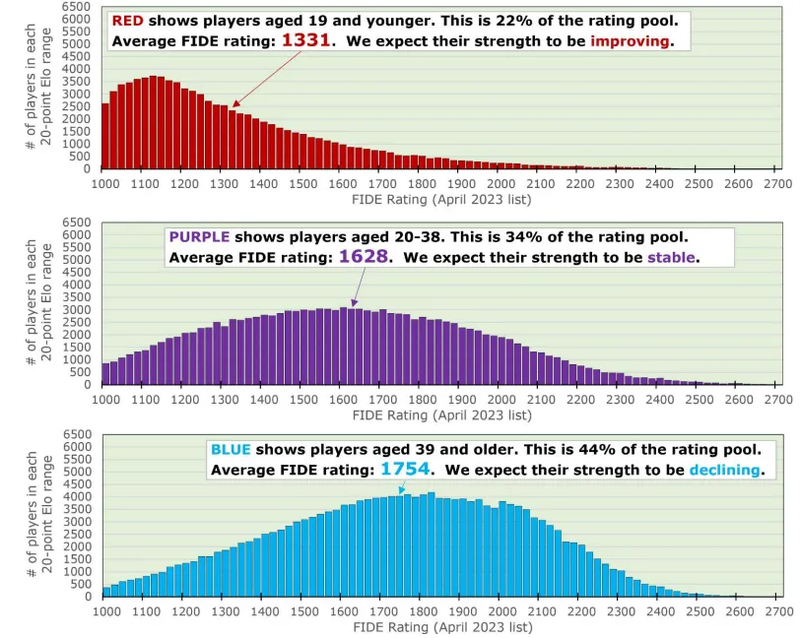

Age segmentations

On page 8 of his Supplemental Report, statistician Jeff Sonas introduced a 3-bin segmentation based on age. I will recast that visualization here, which shows the April 2023 (pre-compression!) rating distributions.

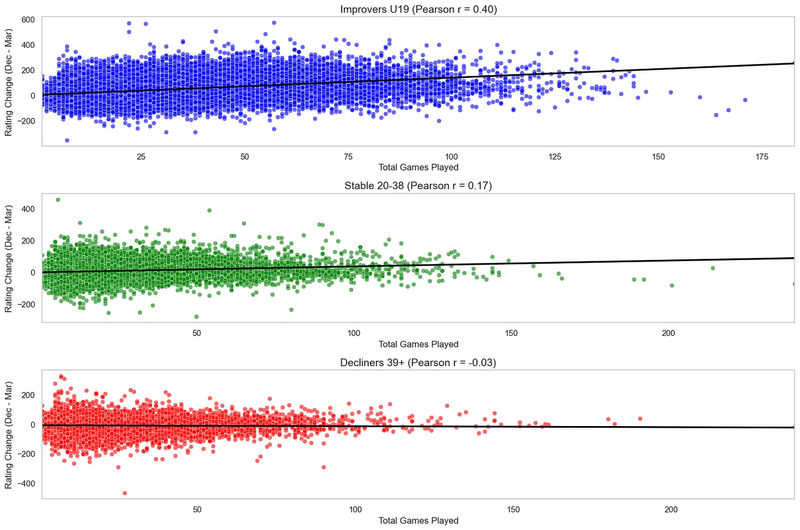

For the narrow interval March-December 2024, I can confirm this segmentation is appropriate when looking at the effect of games played on a player's rating.

Despite the different color coding from Sonas' graph, the relationship is logical:

- Young players (improvers) gain rating consistently by playing more games, as we would expect

- Stable players see a smaller improvement with playing more games

- Decliners lose rating slightly, as expected

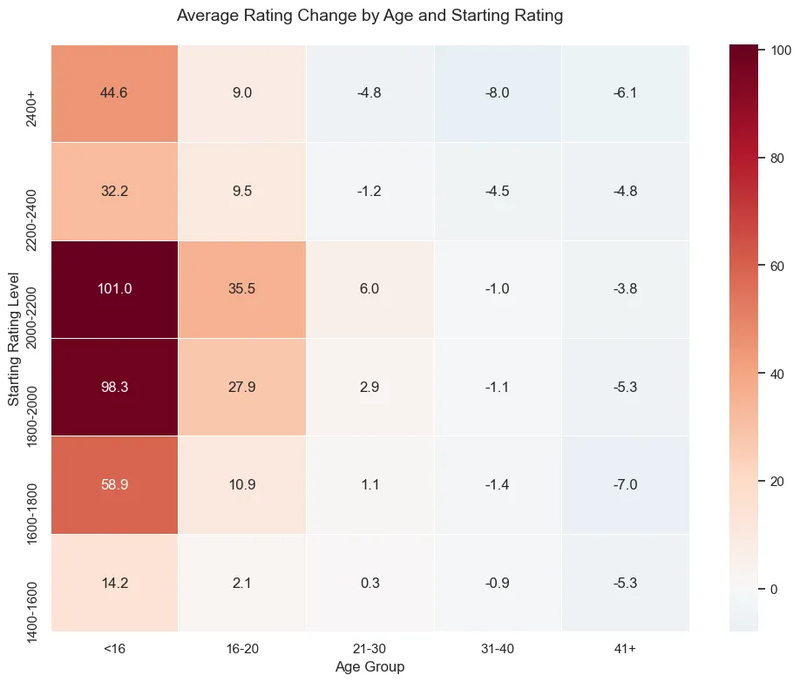

If you prefer to look at more granular age groups, separated into rating bins, here’s that analysis, spanning March 2024 to June 2025:

If by now, I managed to convince readers that young players are the most dangerous to face (since they're so underrated!), that should be extremely relatable to active OTB players. The pain of losing to an underrated junior is all too real. As recently as February of this year, I lost to a 9-year old boy from Ivanchuk's Academy in Ukraine. He outplayed me start to finish and left no ounce of counterplay. Care to guess his rating? Of course it was 1674...

Geographical disparities

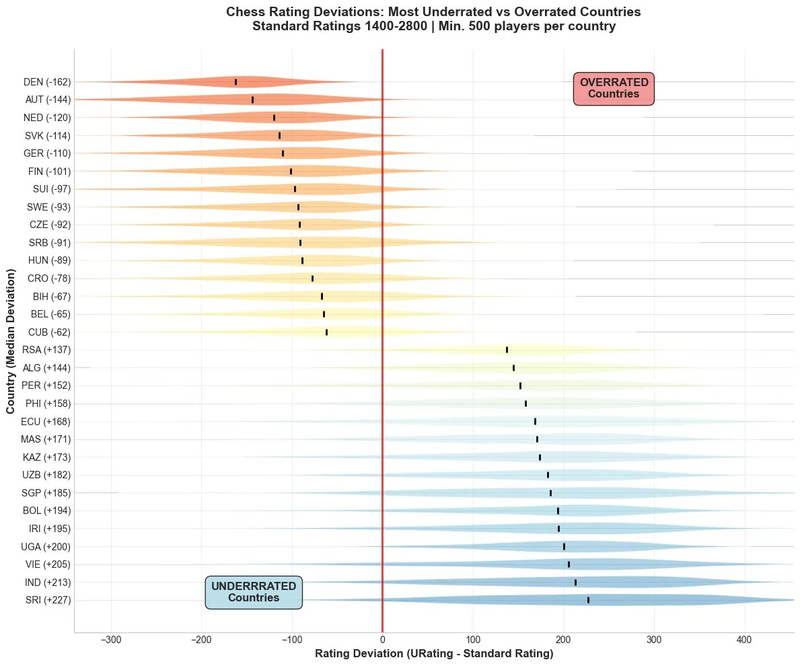

The chart above illustrates what I deem to be FIDE’s biggest challenge over the upcoming years: fixing the huge disparity in rating validity, or eliminating vortexes of rating inflation/deflation that are focused in specific countries.

Methodology: I compared FIDE and URS ratings for players present in both systems, focusing on federations with 500+ players to ensure statistical significance. If you want to refer to a previous discussion on why I deem the URS system to be a good validator and often a better indicator of true playing strength, please refer to this article.

The results reveal systematic geographic biases. Denmark shows the largest overratedness (by 162 points on average), while Sri Lanka shows the largest underratedness (by an average of 227 points). This isn't coincidence, but reflects fundamentally different competitive environments.

Same Rating, Different Reality

A player rated 1800 in Sri Lanka and one rated 1800 in Denmark might share a number, but not a skill level. This is reflected in their URS ratings, but Elo is completely naive to it. This isn’t an isolated mismatch. It's the norm when federations with deflated pools meet those with inflated ones and Elo has no way of knowing.

The static K-factor and single-rating assumption struggle in this dynamic environment with players from various federations mixing in open events. Yet, the example above was merely a thought experiment. Out in the real world, this happens more frequently than before in large Swiss tournaments, where the mixing of federations offers the juniors from underrated countries a huge incentive to participate and “farm” rating from their unsuspecting opponents. A typical example is the Sunway Sitges tournament in Spain, which often attracts a lot of youth participants from India. Here’s a screenshot of Sunway Sitges 2024:

Of the ~20 Indian players rated below 2000, only one - Adarsh D - underperformed their starting rank and finished lower. This is consistent with the belief that amateur Indian players are often more underrated than their professional counterparts (anecdotally, lots of the 2000+ players in the screenshot above underperformed their rating!), and has given rise to a new phenomenon where established European players often avoid tournaments for fear of getting paired to these extremely underrated opponents. However, the discussion shouldn’t be limited to India alone. Federations from Central Asia, such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, also have a wide array of extremely talented juniors, with Kazakhstan scoring particularly well in World Youth Championships recently and sending more delegations to Europe for these enhanced opportunities.

This systemic pressure from deflated pools that are now starting to mix with inflated pools causes a reduction in the participation rate of disillusioned players, and has a ripple effect throughout the FIDE environment. It's my strong belief that once we fix these disparities (by any intervention necessary!), tournaments will be fairer, have better participation, and lead to faster growth of OTB chess worldwide.

David Smerdon, a known Grandmaster and Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland reiterates this geographical disparity and puts a different highlight on it: “It's not an age thing, it's a not-enough-FIDE-tournaments thing. Poorer federations are more likely to have deflated ratings because submitting FIDE tournaments is costly. So, there's a correlation between country GDP and ratings inflation, which some might find problematic.”

While I agree that there’s a correlation between country GDP and ratings inflation, I think further analysis such as multivariate regression is needed to establish which factors dominate. What we do know so far is that a large percentage of active youth players in a federation often leads to a deflated pool in that country.

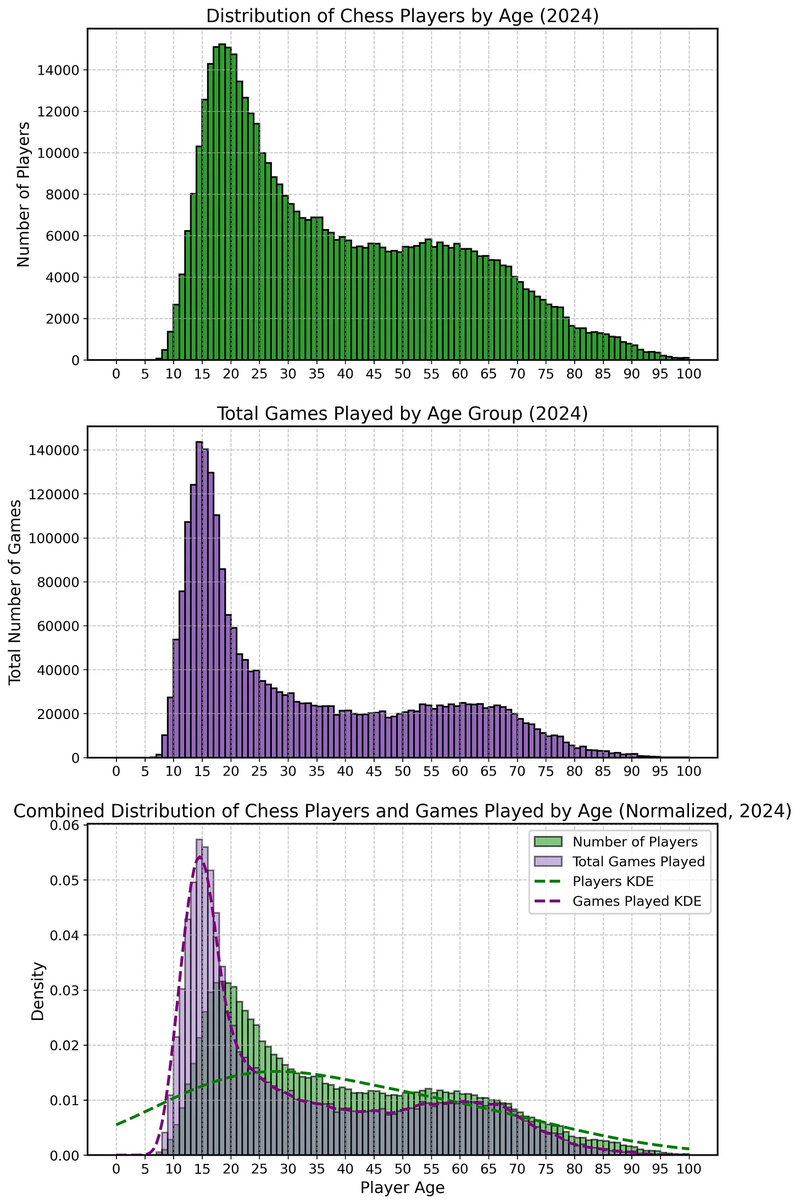

"No country for old men"

From the bottom diagram, it results that in 2024 teenagers have played more FIDE-rated games than their representation. This is a trend that has accelerated post-pandemic and is quite relevant because it introduces a "K-factor asymmetry" into the pool. If there’s often mixing between asymmetric K-factors (say, someone with K=40 facing someone with K=20), we expect the lower-rated youth players to add an inflationary pressure in the system whenever they win, by extracting double the rating points from their more established opponents. And here’s the kicker: even with all the tweaks and this asymmetry, deflation still hasn’t gone away! This suggests that either the more established players are overperforming when facing juniors (hardly!), or that there might be deeper issues with the Elo formula entirely.

5. Why Elo Breaks Down

Elo’s Blind Spots

A system designed decades ago for top players competing in elite round-robin events assumes all players compete under equal conditions. It doesn’t factor in regional differences, economic disparities, or uneven tournament access. It hardly accounts for uneven matchups where players are separated by more than 400 points. The consequences? Widespread rating distortions and unfairness.

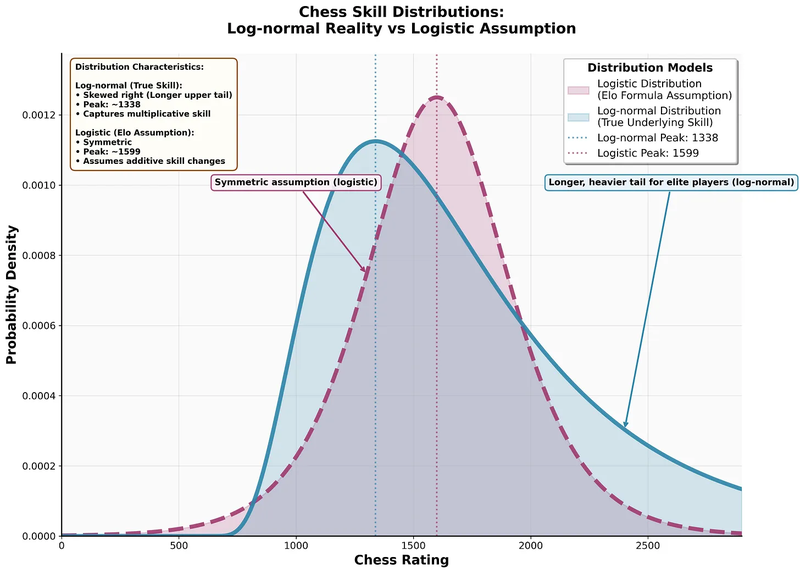

This article has shown both the symptoms (global deflation, geographical rating disparities, youth-driven volatility) and the underlying causes. Elo's core assumptions no longer match chess reality. The system was designed when only elite players competed: a small, motivated group with roughly normal skill distribution and whose ratings were all clustered into a 200-300 point interval.

Today's chess world is different. We have casual players alongside professionals. This creates a 'long tail' distribution where skill gaps are far wider than Elo anticipates. The assumption of a symmetric, logistic distribution is challenged by a more realistic modeling via a log-normal distribution.

Static K-factors

They’re blunt instruments. Fast-rising players get stuck. Declining ones linger too long. A better measure would be a context-dependent volatility parameter. Inactive for too long? There’s no certainty your rating is meaningful. This is where something like the Glicko system (implemented in USCF, as well as online platforms) shines through. It adjusts the K-factors through a continuum of possibilities.

Geographic and economic blind spots

Elo doesn't adjust for regional inflation or deflation, nor does it consider tournament access or federation disparities. A 1900 in Denmark and a 1900 in Sri Lanka? By URS ratings, night and day. Elo sees no difference!

Conclusion: A Future-Proof Rating System?

Chess has evolved since 1970. The rating system hasn't.

We now compete in a world of open tournaments and global mobility. Yet FIDE still relies on a system built for closed, round-robin events between national elites. That system was revolutionary in its time. Today, it’s showing its cracks. FIDE’s recent changes: the one-time sub-2000 adjustment, the reintroduction of the 400-point rule, the rating floor increase to 1400, are all sincere attempts at relief. But they remain reactive and fundamentally tied to an aging core assumption: that Elo is good enough.

We don’t need to burn the whole system down. But it’s time we build something that fits today’s chess world, with some key ingredients such as:

- Flexibility and responsiveness

- Contextual strength estimation

- Statistical modeling that keeps up with how players actually improve

It won’t be easy to replace Elo. It’s embedded into our title systems and our historical lists. But if we value accuracy, fairness, and full objectivity of the rating system, we owe it to ourselves to analyze things deeper. How long can a modern game run on a vintage algorithm?

The chess world has changed. Today, our clocks are digital and our games are online. Our analysis runs deeper than ever before with Stockfish and Leela, leveraging powerful neural nets and machine learning algorithms. Yet, our ratings still lag behind. If we want fairness to keep pace with progress, the time has come to modernize, and not use the same formula as in 1970.

My main suggestion is for FIDE to start tracking URS ratings and display them prominently on each player’s page for a period of ~1 year for a comprehensive evaluation. In the future, running a Glicko-2 type algorithm in parallel might be desirable.

Acknowledgments: I would like to credit Walter Wolf, Jeff Sonas, Ken Regan, and Mark Glickman for their articles, which served as useful inspiration. Thanks to David Smerdon, Mark Crowther, and many others for engaging on social platforms. Also a big shout-out to Chessdom and their editorial board for publishing some of my materials to a wider audience.

This article was originally published June 24 on my personal Substack. This is an upgraded write-up for clarity and focus.

You may also like

Vlad_G92

Vlad_G92Obituary: GM Daniel Naroditsky (1995-2025)

Daniel Naroditsky passed away at the age of 29 in Charlotte, NC, where he resided since 2020. Vlad_G92

Vlad_G92How to Select a Chess Coach: A Complete Guide for Players at Every Level

Finding the right chess coach can accelerate your improvement dramatically. However, with hundreds o… CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… Vlad_G92

Vlad_G92What really matters when choosing a chess tournament

Whether you're chasing norms or just hungry for a better performance, choosing the right tournament … Vlad_G92

Vlad_G92