Becoming Unkillable

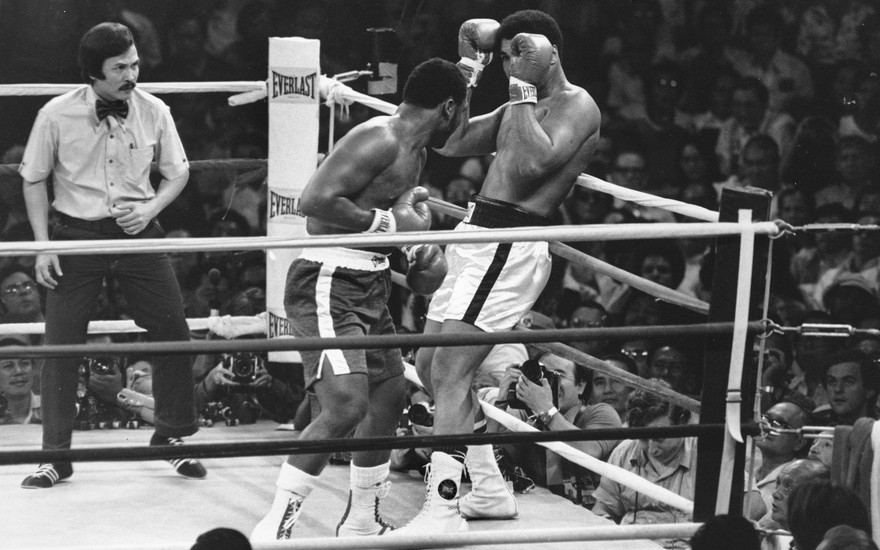

There are two ways to die.You’re lying on the bathroom tiles in the toilet of some stinking pub. There’s blood streaming out of both your nostrils. You’ve got one broken arm, a few cracked ribs, and a big lump on the side of your head where it’s been bounced off the porcelain rim of a nearby sink. Above you stand the two heavy pieces that put you there, waiting to finish you off.

The you that’s lying there has a choice.

Option 1: Wallowing In Your Misery

The first option is to curl up in a ball and think about the moment you landed on your arse. You can dwell on the blow you let get past. You can beat yourself up for not seeing it coming. For not blocking it. You can curl up and wait for the death blow to land. You can lie there with tears streaming down your cheeks. You can stay on your back, belly exposed like a submissive dog.

You can even beg for mercy: the real-life equivalent of smashing the ‘draw offer’ button over and over again. That’s one choice.

Option 2: Fighting Until The Bitter End

The other choice you can make, is to drag yourself up onto your elbows and smile a bloody-toothed grin at the two standing above you. You widen your eyes and start laughing. That gives them pause. Instead of two big bodies standing over you waiting to finish you off, you're now facing two confused looks who are wondering what this sorry-looking lunatic could possibly be laughing at.

Now, you still know that the chances of this ending well for you are pretty slim. But you drag yourself up anyway. You look the two heavies in the eyes and you think: I’m probably going to go down here. But before I do, one of these fuckers is going to lose an eye.

Now.

Who’s it going to be?

Mental Resilience

The chances are that things will not end well for either versions of the you that I described above. But you can bet your arse that one of them has a fighting chance, and the other one might just as well resign.

These two deaths are how I picture the two ways to lose a lost position. Mental resilience is worth a lot in chess. And the lower rated you are, the more mental resilience is arguably worth. Because the more likely it is that your opponent, who’s also in the lower rated ranks, is going to blunder back.

If you're down a piece, the chances are that, if you can put up a bit of resistance and hang in there for another 10-20 moves, your opponent might just hand you the chance to get back into the game.

Now this is all easier said than done. So, how exactly do you become unkillable?

Rocky montage time.

The Pre-Match Mindset

I like to send my chess students a voice message before their important games. I find it’s rarely useful to talk about the chess in these moments, although we will sometimes mention a few last-minute things about openings.

Instead, I focus my pre-match talk on the mental game. And one of the things I always tell them, is to be unkillable. I literally say that. Sometimes I dial the Scottishness right up and I shout it.

I can get a little bit carried away.

At times I like to think of myself as the chess world’s Sir Alex Ferguson: “And you better be un-FUCKING-killable when that game starts. Or I will hunt you down like you allowed your opponent to hunt down your fucking queen in the last match”.

I would like to point out at this stage that although I delivered that speech to what social services described as my ‘final child student’ (Alisha, age six) she did go on to win that game.

And she was unkillable.

I only teach adults now.

Click here to book a free 60-minute chess lesson with me.

Side note: if you struggle to understand my humour, you can also reach out to me with a passive-aggressive or simply aggressive message about the treatment of my fictional student Alisha, on Twitter or right here on Lichess. By following me on these platforms you can also get notified about when my next blog posts are available to offend you further.

All jokes and advertising aside. Whether you have a coach or not, if you can remind yourself to be more resilient, to be unkillable, before each game starts. Then even if the worst does happen and you blunder a piece or find yourself in a much worse position, you at least give yourself a much better chance of pulling yourself up and laughing in the face of your opponent - like a maniac.

Take A Minute

When we make a face-melting error, the immediate feeling isn’t that far removed from taking a heavy blow to the chin. It can daze you. Unfortunately, when we hit the canvas in chess, there is no referee there to step in and stop the fight.

But that is exactly what we need to do. We need to be our own referee.

When you make a terrible mistake, you need to be the one who steps in. I will often literally stand up and just get away from the laptop, or the table. Closing your eyes and sitting back can also work. It is just something that cuts you off from the chess board. You need to forget chess at that moment.

The last thing you want to be doing, is making a move from the mental state of someone who’s just been knocked down.

Right now, we need to gather our senses.

You don’t want to be making decisions with a mental fog clouding your judgement. We need to clear that fog first. And once we do, not only are we less likely to make a second mistake, we can often realise that the actual situation isn’t as bad as the feeling we first had in the immediate aftermath of the error.

When we overlook something, when we are surprised by a move, our minds can often bias our judgement into thinking that things are much worse than they actually are.

By calming down we can look objectively at the situation. Something I failed to do in my last game in the fantasticly organised Lichess Lonewolf League.

How Not To Be Unkillable

My opponent's last move was Nb4. Here I was guilty of not following my own advice. Up until this point, I’ve had a much more pleasant game. But here, I just made a calculation error. I saw this discovered attack against my queen, threatening the fork on c2. But in my calculation a few moves earlier, my idea was to meet this move by simply retreating the queen to c3, saving the queen and preventing the fork. Unfortunately, queens can’t move through knights.

I was so annoyed with myself. I was upset. I had made an inexplicable error in visualisation. Up until this point, I had a big advantage on the clock and I felt my opponent's position was cramped and unpleasant.

After I saw my mistake, my first thought was that my queen was trapped. I was going to lose her. I thought the game was over. What I needed to do was get some distance from the chess board. I needed to first of all check if the negative emotions I was experiencing because of the move were justified. If I had done that I would surely have seen the fairly obvious Qc7. A move that actually maintains an advantage.

However I was not, at that moment, unkillable. I didn’t take the time I needed.

Instead, clouded by my own negative emotions, I made a second error on the very next move. I played Na7, blocking the threat against the queen and self-pinning. Now I am definitely worse, the advantage has swung to my opponent.

But the game isn’t over, yet. At that moment, after my double error, I was evaluating the position as something around -5 or -6. In reality, it was around -1.5. Not pleasant for sure, particularly after holding an advantage for the whole game up until that stage. But the game was far from over.

By not allowing myself the space to recover emotionally from my own errors, I made a third and final error. My mind was not seeing the position objectively, it was seeing it through the negative lens of my own calculation error and subsequent second mistake. And my third and irrecoverable error?

I resigned.

So clearly, there are still lessons for me in here, too. I must not only practise what I preach, but must also work hard to improve in the psychological elements of chess that have just as much of a bearing on our results as the chess we actually play.

Consider this the first in a series of posts on what I’d like to call ‘non-chess chess’: the psychological and practical elements of the game we need to complement our chess knowledge and skills.

Adult Improver Coaching | Free Trial Lesson | Patreon | Twitter | Linktree

When It's Not As Bad As It Seems

So, what actually happened that led me to resign before I was killed? Something unexpected.

Unexpected is not bad or good. It is unexpected. I had missed something. Missing something is technically a mistake, a human error, but that doesn’t mean that human error must translate to being a chess error. In chess terms, it might not even be an inaccuracy.

Only in my mind had I made a game-turning error from which I couldn’t recover - something that simply wasn’t true.

Remember that just because a move is unexpected or is something you missed, that doesn’t mean the move is disastrous. If we take a moment to gather ourselves and calm down, we can then look at the situation objectively.

If we look at the position through the negative lens of our own emotions, we will struggle to see anything but the negative. Just like in life, a negative mind can only see negative things, in chess the same is true.

When It Is As Bad As It Seems

Taking a moment to recover psychologically is important. But what if we calm down and objectively look at the situation, and discover that it really is just as bad as we first thought? This is where the true art of becoming unkillable strikes.

Let me tell you the story of one of my student's games. I call this game ‘’the four-headed snake’’. Because my student's opponent had to lop off his head four times before he finally lay still. Watching this was epic. It was the chess equivalent of the last scene in Gladiator. Three times I had my head in my hands as I watched my student blunder, claw his way back to an even position and blunder again. He even went down a queen only to win it back with a desperate mating attack.

This game took place a few weeks after we looked at a defeat of his in which his surprise at a move caused him to evaluate a position negatively. A position in which he was comfortably winning, yet his mental bias caused him to perceive the game as much worse for him. Just as I had in my own game.

He told me afterwards, that after each of his blunders, he had stood up and taken a little walk, came back to the game, and strove to be unkillable. He took not one but three totally hopeless positions and gave himself something to fight for.

He clawed his way across the bathroom tiles, dragged himself up on the rim of that sink and fought.

It was truly inspiring. And even though the result was still ultimately death, it was a glorious one. It was a death to be proud of. And I was so proud. Winning back that queen was the chess equivalent of gouging out an eyeball as a last ‘fuck you’.

It was saying to the opponent: I will not die, you will have to kill me.

And that, in a nutshell, is how you become un-fucking-killable.

Thanks for reading!

I am offering a 60-minute trial lesson for free.

Support the blog by signing up to my Patreon page.

To get notified about future articles, follow me on Twitter or here on Lichess.

Read more about my coaching for Adult Improvers <1000 FIDE or online equivalent.

Freelance writing enquires to TheOnoZone@gmail.com.

Use this link to get 20% off ChessMood memberships from fellow blogger GM Avetik Grigoryan.

More blog posts by TheOnoZone

Adult Chess Clock

I used to say that nobody doesn’t have the time for something, they just don’t want to prioritise it.

The Ono Gambit

I am getting older.

Losing Consciousness

It was game over.