"All Izz Well": Overcoming Negative Emotions on and off the Chessboard

Chess is more than just a game—it’s an emotional journey filled with highs and lows. In my career as a professional player, chess has been a source of both joy and hardship. In this post, I’ll share my journey and the lessons I’ve learned about overcoming negative emotions and countless struggles to embrace the beauty of chess, even in its toughest moments.The C is for the courage I possess through the trauma

H is for the hurt, but it's all for the honor

A is for my attitude working through the patience

Money comes and goes, so the M is for motivation

Gotta stay consistent, the P is for persevere

The I is for integrity, innovative career

The O is optimistic, open and never shut

And the N is necessary 'cause I'm never giving up.

"The Champion" by Carrie Underwood and Ludacris

Feeling sad and feeling hurt are two entirely different emotions.

In chess or in life, one can feel sad for many reasons. For me, sadness comes when I face the consequences of my mistakes—losing a game, making repeated blunders, not meeting expectations, being criticized and disciplined by my coach. The heavier the consequence, the deeper the sadness, and the longer it lingers. However, when you are sad, you still have enough awareness to find ways to improve and recover quickly. In this sense, sadness can sometimes be a productive emotion, helping you seriously reflect and correct mistakes to grow.

On the other hand, feeling hurt is different—it often stirs up anger, self-pity, loss, discouragement, and even despair. The feeling of being hurt leaves you without the rationality or motivation to do anything meaningful—only the pain inside remains.

Chess has been a powerful way for me to heal from the hurts life has brought. Immersing myself in the game allows me to forget everything else for 5–8 hours, until I become so exhausted that I fall asleep without realizing it. Solving combinations, doing puzzle racers or rushes, and playing blindfold or bullet chess are my three favorite activities to overcome negative thoughts in life.

> What does it feel like to be hurt because of chess?

- Realizing at 8 years old that my father wanted me to play chess just to earn money.

- Seeing my father flip the chessboard when I was 9 because I wouldn’t want to practice chess to "gain fame and fortune."

- Being compared to other kids in my age group.

- Losing in a row and being abandoned by my coach, who stopped preparing me for the remaining rounds when I had no chance left for prizes.

- Being a stubborn child and having my coach refuse to teach me anymore.

- Feeling like people only cared about me because I was good at chess: When I failed a tournament, no one stood by me—not even my parents or coach.

- Losing my passion and realizing my dreams might be unrealistic.

...

How to "cleanse" your mind from negativity

I’ve spent years figuring out how to overcome negative emotions. I’d like to share some advice from Super Coach Ramesh, someone I deeply admire. His guidance has shaped both my playing style and my approach to life.

During an online class, I asked GM FST Ramesh:

"I play well, 1900+ level. But before my game in any tournaments, I always feel sad and upset when I see my opponent has their parents beside them, taking care of them, or noticing their coach whispering something to them while glancing at me. This tremendously influences the quality of my games. I think it is because I have been going to tournaments all by myself since I was a kid. My parents never gave me a call or encouraged me between matches either. How should I improve my mental strength? Should I find a personal coach or a mentor? What do you do to encourage your students?"

GM Ramesh’s response was profound. I’ll quote 99% of his words he said in the class verbatim here:

"Playing chess is not all about chess moves, not about d4, e4, bishop moves, knight moves. It’s a lot about psychology—50% psychology and 50% chess. It’s not enough if we work only on our chess at home; we also have to work on our mindset and on our psychology on a regular basis.

Now imagine this: there’s a clean room. Then I close all the doors and windows very tight, and then I go out of the room, lock the door. After one month, I come back inside. Nobody has entered the room, nobody has disturbed anything. But will the room remain the same, or there will be some changes in the room, what do you think? There’ll be some smell, there will be a lot of dust in the room, right? Spider webs, maybe some bugs, maybe mosquitoes, lots of different insects. Spider webs for sure, dust for sure, right. Now, again I close the door, and after 10 years, I return, will the room be the same? Nobody has entered the room. Maybe there are some cracks on the wall. The paint would be peeled off. It would look like a haunted house.

So what I am trying to say is, imagine that room as your mind, okay. Even if you don’t think negatively, if you’re just doing daily things, don’t have any negative things about others or about ourselves, still some negativity will accumulate in your head. Because people are talking of negative things, bad things happen, sad things happen, right? Automatically in our head, some negative information is worsened without our knowledge, without our control. Now as far as everybody is concerned, we go out, dust settles in our body, we take a bath with soap then the dust's gone. We take a bath everyday to clean our body. But what about our mind? The negativity comes from outside, from our interaction with others. Some negativity on a daily basis keeps accumulating. So just like we clean our body everyday, it would be nice if we can clean our head also on a daily basis.

My suggestion: do some meditation—just a few minutes every day, like taking a bath for your mind. Not related to chess stuff, but you have to do something to make sure that the negativity does not accumulate little by little on a daily basis, and on a period of time, it becomes a little bit too much. What you can do is you can read some positive books with some positive messages once in a while, get some inspiration, get some positivity in your head, or self-teach, you can everyday tell yourself, today, like when you get up in the morning, before you get up from the bed, you can tell yourself “I’m going to be a positive person, I’m going to work really hard, I’m going to give my best." Do some positive messages because this kind of positive message is very rarely coming to us these days, right, parents, or friends, or schools, universities, society—we don’t get that kind of positive message very often these days. So we have to do the job for ourselves. So everyday, similarly when you go to bed, you can tell yourself, today I did ABC good, CDE not so good, tomorrow I will work on the CDE and improve myself. Mental toughness is very important. When I take lessons with my students, even with Prag or other GMs, we discuss a lot about psychology, how to avoid negative thoughts, and similar issues, and it’s very important.

(This might sound a bit off-topic, but I've noticed FIDE Senior Trainers often share these kinds of stories to make their lessons more relatable and easier to grasp.)Regarding the question, "I feel lonely during tournaments because nobody accompanies me". Now, there're a few things you should be very clear about: One, you’re playing chess mostly for yourself, okay, be very clear about this. I love to play chess, I want to achieve some good things in chess, I want to show improvements, and I’m doing this for myself. And once you feel very strongly about this, it also means that you’re not doing this to impress others. You don’t have to win every game and look good in others’ eyes. It’s not necessary and also not possible, unless you are Magnus Carlsen! So when we lose games, others might think or feel bad about ourselves, which is perfectly fine, we can handle it. Don’t be affected by what you think others may think about you. What others think about you is not your problem. So you have to do it for yourself. The second thing is, we have to enjoy everything (the positives around us). If someone is being supported by their parents and coaches, you should feel good for them, but you don’t have to feel bad for yourself. Supposedly I drew my game, and one of my friends won his game, I should feel good for him and say to him, “You won your game, I’m happy for you. I drew today and I’m already sad, but I’ll bounce back and shine tomorrow." Try to take it as something none-desperate. Try to take these experiences as opportunities to build resilience and enjoy the journey."

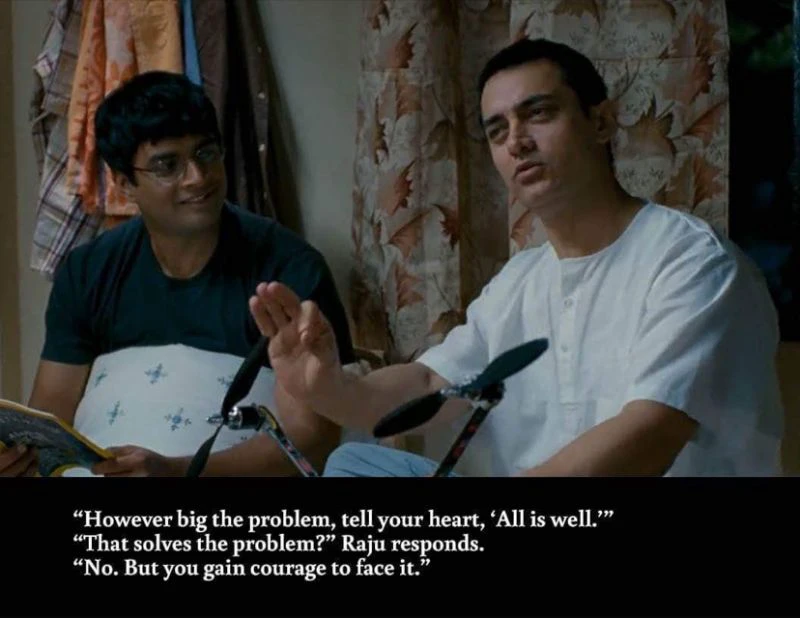

I carry Sir Ramesh's words with me, and every time I feel lost or broken, I hold onto them with all my might, then everything would be alright. His words become my anchor, like the mantra "All iz well" from my favorite movie 3 Idiots.

After every painful loss, I ask myself: if I could turn back the clock and knew I would fail, would I still choose to play in that tournament? The answer is always “Yes!” Because I do simply love chess. No matter how many hardships I face, no matter how devastating the failures, I would still choose chess over and over again.

The Struggles of Playing Chess in the US

The lesson with Coach Ramesh happened during one of the most challenging times in my life. By 2020, I was in my third year of studying abroad in the US, far from home and balancing countless struggles. Back in 2016, I achieved my direct WIM title by winning the Asian G18 Championship in Mongolia, and was at the peak of my chess career. Yet, later that same year, my life took a significant turning point when I suddenly received a scholarship from a boarding school in the US. My performance at the World Youth G18 in Russia that October suffered, as I was consumed with anxiety about moving to the US immediately afterward. Within just two weeks from the Russia trip, I passed my US visa interview, purchased 24-hour-long flight tickets, and flew alone, halfway around the world at the age of 17.

The transition was overwhelming, and balancing chess with academics became an uphill battle—especially as I’d been in schools for gifted students since grade six and was used to excelling in both. For the first three months at the boarding school, I felt like I was deaf and mute—I couldn’t talk to anyone or understand what they were saying (schools in Vietnam only teach grammar and reading, but neglect speaking and listening). My ESL classes required me to learn over 1,000 new words each semester. However, while I could write them down, I struggled to pronounce them correctly. Fortunately, I had an incredible teacher who patiently listened as I slowly spelled out each letter in the words I wanted to say, and helped me pronounce them. This same teacher took me to my very first chess tournaments in the US, and that’s when I began to see a glimmer of hope in my life.

Okay, then let’s get back to the chess story.

Participating in tournaments as a young-dumb-and-broke international student in the US was an entirely different experience.

Studying abroad was not only financially draining but also emotionally and physically challenging. As an only child with congenital heart disease (finally cured in 2022), raised by a single mother, I felt immense pressure. Every tournament required careful budgeting. To save costs, I meticulously planned every trip, sometimes spending hours calculating the cheapest possible options. I never stayed at the venue hotels but booked Airbnbs within walking distance to save on costs (if too far then I had to estimate the extra cost for uber rides). For travel, I compared all possible routes: a direct flight (which I could never afford), a bus to another city, followed by a train, then an Uber from the bus/train station to the final destination. I weighed total costs, travel time, and safety, but cost always mattered most.

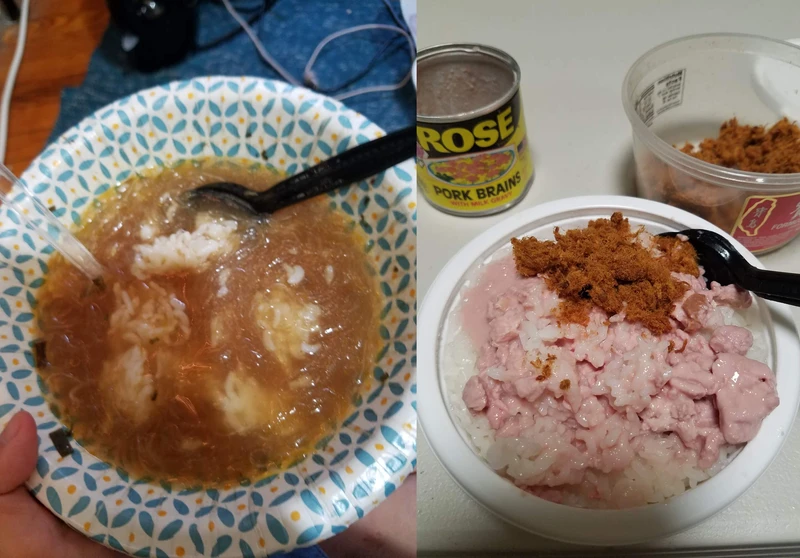

One memorable trip involved finishing my final game at 9 pm on a Sunday, taking a 14-hour Greyhound bus overnight, and arriving just in time for my Monday morning class without dinner or breakfast. To save money on food during tournaments, I packed instant noodles and a water boiler. Restaurants, even fast food chains like McDonald’s, were a luxury I couldn’t afford.

I remember one moment that truly tested my mental strength. Before a game against a 13-year-old rated 2300 USCF, I saw his mom tying his shoes while he casually enjoyed a box of sushi she ordered for him. I swallowed back my tears and tried to focus, but the negative thoughts just overwhelmed me, leading to an easy loss.

Instant noodles are too common for an illustration, so instead, here's a picture of my two favorite dishes during tournaments: rice mixed with glass noodle soup or topped with meat floss and canned pork brain?!

The SPFGI and My Fight for Webster University

Webster University, where my idol - GM Le Quang Liem had graduated from, has always been my dream school of all time.

To pursue this dream, I participated in the Susan Polgar Foundation Girls’ Invitational (SPFGI), where the winner would receive a full tuition scholarship to Webster. I competed twice, at ages 18 and 19. My first attempt was in July 2017. I traveled to the US for just one week, returning to Vietnam after the tournament ended—just as I adjusted to the timezone—and flying back three weeks later for grade 12, having calculated that returning home was cheaper than staying in the US until school started. During the trip, I enjoyed visiting my dream school and solving puzzles, finishing 2nd in blitz (no prize, sadly). I also met my childhood opponent, Zhou Qiyu, whom I hadn’t seen in 10 years since we both first met and played the longest game of our lives—over five hours—in Turkey at the World Cadet G8. We were thrilled to see each other again and vividly remembered that epic match.

I didn’t win any prizes that year, making SPFGI 2018 my final chance. My mom, who had never taken any flights in her life before, accompanied me for the first time to support me and visit my prospective university. That was the first time my mom observed me in a chess tournament, as my family never had the means to accompany me before. I performed poorly in blitz and puzzle-solving, worse than in 2017, so the classical games were my final hope. Unfortunately, I drew with a lower-rated player in Round 3 and knew that losing one more point would eliminate my chances for the full scholarship. In Round 5, I faced the top seed, Thalia, who had already won both the blitz and puzzle-solving events. I was so anxious but I concentrated fully and gave 200% of my effort. That game earned the brilliancy prize, selected by Mrs. Susan as the best game of the tournament.

My game that won the $100 brilliancy prize

However, in the final round, the fear of losing everything was overwhelming (by then I had not known that I would win the brilliancy). I didn’t want to disappoint my mom, especially when she had her high school friend who resided in Missouri came to visit, and they both waited for my last round. I was half a point ahead, so I agreed to a draw in a better position, thinking it was the safest option to secure co-champion status. However, there were 5!? co-champions that year with 5/6. The two players with the highest tiebreak, me and another girl, had to play an Armageddon match to decide who would receive a full scholarship, and I got the black pieces. Blitz was never my strength, and I lost painfully. I ended up with only a 70% scholarship, which I couldn’t afford to cover the remaining fees. It was a regretful experience that took me a long time to forgive myself.

Later, while reading Mrs. Susan's Facebook posts, I discovered that she strongly opposes agreed draws. Since then, I have never agreed to a draw in the middle of a chaotic battle again.

The Valley of Disappointment and Desperation

With no time to rest or reflect, my mom and I took an 11-hour train (while carrying 5 pieces of luggages) from St. Louis to Madison to continue with two more tournaments: the National Girls Tournament of Champions (NGTOC), where each state’s top girl competes for a $5,000 prize, and the US Open.

At NGTOC, I faced another critical decision in the last round: A draw would secure me $500 and bronze medal, but a win got me the champion title with $5,000 prize. Still haunted by the SPFGI just five days earlier, after reapeating the moves 2 times, I pushed for a win in a slightly worse position, with no real advantage or hope, and lost. Exhausted from back-to-back tournaments and travel, I performed poorly at the US Open, which had double rounds every day with a time control of 40/120, SD/60, d5 (a game could last over 6 hours). I recall one game starting at 7 pm and finishing at 12:30 am, with a loss. My mom and I walked for another 20 minutes back to our Airbnb. Despite being utterly exhausted, I couldn’t sleep. My brain was under intense pressure and the sleepless nights continued.

During the final round, I witnessed a senior player collapse on the floor and pass away from a stroke. That was the only time I genuinely felt scared and questioned whether I had had enough of chess.

A Coach and A Competitor: The Sacrifices Behind

I later attended an all-women’s university in Virginia with financial aid of about $42,500/year, which eased my burden as my chess earnings could cover most of the expenses. I loved my college life, but my passion for chess was still unwavering, so I started to look for chances to play. To fund my tournaments, I started coaching chess online for 20 hours a week and working as a math tutor on campus for another 20 hours, all while maintaining my grades on the Dean's List. However, after a year, I realized that working to afford tournaments was a poor way to improve. My rating gradually but consistently dropped, and the quality of my games suffered from exhaustion.

I decided to focus on saving money for lessons from world-class coaches. After six months working my @ off, I finally was able to register for long-term online lessons and training camps. However, COVID hit, and the lockdown took a toll on my mental health. Trapped in the US alone all summer without tournaments to test my skills, my chess strength continued to decline.

I’ve spent my youth in a relentless cycle: experimenting, failing, adjusting, and trying again. To this day, it hasn’t stopped. I work as a coach to fund my tournaments and lessons, and when the funds run out, I focus on coaching again.

Coaching allows me to inspire others and fund my own chess career. However, coaching beginners or very young kids somehow slows my personal improvement and harms my chess performance in tournaments if I coach and play at the same time. One time, I started with a perfect 3/3 but had to stay up until midnight preparing for my students' important national games, which coincided with my open tournament, then I lost 4 in a row. I also sacrifice my entire summers: for three months, I dedicate myself as a full-time coach, running a summer chess camp that functions like a mini boarding school for kids from across Vietnam to stay overnight. I also travel with my students to national and international tournaments, taking care of them on behalf of their parents...

While I love coaching and adore my students, I also long to be a warrior on the board, fighting my own battles.

The Journey Continues

Chess has brought me moments of triumph and regret, financial struggle, and personal growth. From traveling alone across the US for tournaments, subsisting on instant noodles, and sleeping through sleepless nights, to losing decisive games in heartbreaking circumstances, my journey has not been easy.

Yet, it’s in these moments of struggle that I’ve learned the most about myself—not just as a chess player, but as a person. I’ve come to accept that my path in chess is not linear, and success isn’t guaranteed. What matters is the courage to try, to keep improving, and to embrace the lessons failure brings.

Today, I am both a chess player and a coach. My love for chess burns brighter than ever, whether I’m teaching my students or fighting my own battles on the board. Balancing these two roles is challenging—coaching kids while striving for personal improvement often feels like a tug-of-war. Yet, every time I see the joy and progress in my students, I am reminded of why I chose this path. And every time I sit down at the board, I am reminded of why I continue to play.

Chess is more than a game to me. It’s a way of life—a constant challenge, a source of healing, and a reminder of what it means to persevere. No matter how many times I fall, I will always rise again, because this is the life I’ve chosen, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

"All Izz Well"

You may also like

IM theScot

IM theScotLife Hacks for Getting to IM

A post about the life-skills that help you in chess. FM Patrocl

FM PatroclAll Top Chess Players Are Superstitious — Or Are They?

In this article, we’ll explore some amusing cases related to chess players and their superstitions. GM GABUZYAN_CHESSMOOD

GM GABUZYAN_CHESSMOODWhy Being Amateur Might Be Better Than Being Grandmaster

Discover the hidden advantages of being an amateur chess player compared to professionals, and learn… CM HGabor

CM HGabor