Science of Chess: A Bout of Confirmation Bias Over the Board in Fargo, ND

A return to OTB play with the Fargo Chess Club: Some wins, but some blunders too!This past Sunday I competed in the Fargo Chess Club's 2023 New Year's Open. While I haven't been an active member of the club, they've been growing steadily since their founding in 2021 and have held a bunch of successful tournaments in downtown Fargo at the Front Street Taproom. The venue is easily walkable from our house on the north side of town, so what's an NDPatzer to do but start the new year off with a little bit of face-to-face play? The tournament was 5 rounds of USCF-rated G45/d5 play and attracted 35 players from around North Dakota and Minnesota (we might even have had a rogue Canadian, but I'm not sure). I set my alarm slightly on the early side for a weekend morning, made myself a power omelette for breakfast (spinach, feta and everything bagel seasoning), and walked downtown nursing visions of victory.

image

Incidentally, Downtown Fargo is totally charming and fun. If you've never been to North Dakota, I'm here to tell you that you'll probably have a great time. Besides, now you know who you can ask for restaurant recommendations before you travel.

Overwhelming victory wasn't really the thing I was picturing, if I'm being honest. I tend to be too realistic for that genre of daydreaming and past experience suggested a more modest goal for myself. Last year at about this time, I entered the FCC's 2022 Frostbite Open, which was my first tournament since rebooting my chess career. It was great fun, but I didn't put on the best performance - I entered the tournament with a rating of 1120 (which was where my rating had collected dust since about 1993) and left with a minus score and a rating of 1078. Objectively this wasn't a surprising outcome: I'd only prepared by beginning to play online a bit (about 20 rapid games or so total) and watching enough GothamChess videos to decide that maybe I should play the London more often. In the year since that tournament, I like to think I've learned a lot. It turns out I don't like the London at all, for example (I'm an e4 guy now), and I've put in some time learning an opening repertoire that I do enjoy and have some confidence in. I've also spent the year playing a lot of Daily/Correspondence chess to give myself time to practice calculating and to learn about opening lines. As the date of the New Year's Open drew closer, my online ratings climbed across all the time controls that I play, which felt like a good sign. Something seemed to have clicked a little bit for me in the past month or so, and I felt like I was getting more comfortable with a larger set of opening lines, seeing more good tactics, and developing into better positions as I played. I was eager to see how this all translated into OTB play again and (hopefully!) to recover some lost ELO.

Before I say anything else about my games, I want to give credit to the club for putting on a great tournament. The Front Street is a cozy place to play and the club's officers kept things moving and well-organized. Board 1 was streaming live all day via a digital board and pairings/standings were updated smoothly throughout play. This was an excellent event, and I'm looking forward to playing more with these folks. Here's a view of the upper floor of the taproom, which is where the top boards played throughout the day.

image

Upstairs chess at the Front Street Taproom - top players get to sit further from the door and the North Plains chill when people come in from the street!

Round 1 pairings go up and I'm matched with an opponent who is rated a little above 1500 - I'm actually kind of excited about this. I hear one of the top players in the state say from a nearby board "This is the round for upsets!" and I'm wondering if I could be one of them. I feel like that 1078 number doesn't reflect my current playing ability, but what does? I can't imagine I'm objectively at the1500 level by a long shot, but am I close enough to pull off an unexpected win? I try to decide if the guy across from me looks like he didn't get the best night's sleep or neglected to put the bagel seasoning in his power omelette. Maybe. Just maybe. I've got the White pieces, so it's 1.e4 c5 and I try my hand with the Smith-Morra gambit again. He seems surprised by this (talking with him after the game, it turns out that he was) and takes a loooong time to think after about move 7 or so. I'm encouraged - am I catching him a little out of his knowledge base? He hasn't done anything obviously bad, but he seems uneasy and his position feels a little cramped to me - if I'm him, I decided I'm probably a little annoyed that I can't take a ton of space yet. Maybe this is happening! Maybe I'm starting to pull off an upset. I look at the position below after his 14th move and try to decide what my next steps ought to be. Take a look yourself and see what you come up with.

Alright, alright...it's not like I've got anything amazing going on here. I was still feeling encouraged though! The thing is that the engine says this is something like a -0.5 position, which for players rated at 1087 and 1530 respectively probably means it's reasonably playable for both parties at the moment. Ah, but not if one of those parties is me at the start of this tournament because here is where I make my first big mistake of the day with 15. Rd3?? and hang my Bishop out to dry.

"Why?" You may rightly ask - "What did the bishop do?" There is a game-specific answer I could offer, but it's not going to satisfy you. It's not like I had some grand but misguided plan involving sacrificing this piece, you see. I want to hold off on explaining what my plan actually was here because there's a more general principle I want to talk about rather than detail my specific thoughts game-by-game. For now, let's let my blunders have their moment in the sun so we can talk later about where they might come from as a group, and how to try and stop them from showing up quite as often. In pursuit of that goal, I'm actually going to take you all the way to the end of the tournament - here's the critical position from my Round 5 game against one of the FCC officers.

This arose from a Scotch Game I was feeling quite good about, especially after my opponent castled on the queenside. I felt like this was a case of him "castling into it" and I thought I had a real chance to close the day with a victory on one of the upstairs tables. So what did I do? I wrote the words SLOW DOWN on my scoresheet, looked at the position above and promptly played 11. b4?? which just abandons the pony to get eaten by the Queen. Much like Round 1, the rest was predictable and uneventful. Oh, I made my remaining pieces plenty annoying for a decently long while, but the outcome was never in any doubt. My tournament day ends as it begun, and I'm bookended by losses that resulted from truly bad oversights.

On the walk out of the Front Street, I couldn't help but think about my previous post focusing on some of the cognitive science ideas in Kotov's book. In particular, I'd noted his interesting comments on why players (even good ones!) hang pieces like I did, and otherwise overlook responses by their opponent that lead to terrible outcomes for them. What is going on there? Why didn't I see that these pieces were in danger? It's not like visual crowding or any other obvious perceptual mechanisms I can think of should have been a problem for me - I simply didn't think about the possibility that my bishop and my knight were going to get snatched up like they were. Ultimately, I think these errors on my part were a perfect example of confirmation bias affecting my decision-making over the board. The question is: What do you do about it?

Let's start by defining what confirmation bias is, though you may have heard the term before in other contexts. Briefly, confirmation bias refers to a pervasive tendency to favor information that is consistent with your existing beliefs. As a sort of corollary, that tendency also frequently entails minimizing or outright ignoring information that might contradict your expectations. What this means in many settings is that people make systematic decision-making errors because they don't actively look for or examine information that might lead them to reject something they think is true. In chess (and in lots of other settings) that's exactly what we need to do to make the best decision possible and therein lies the problem.

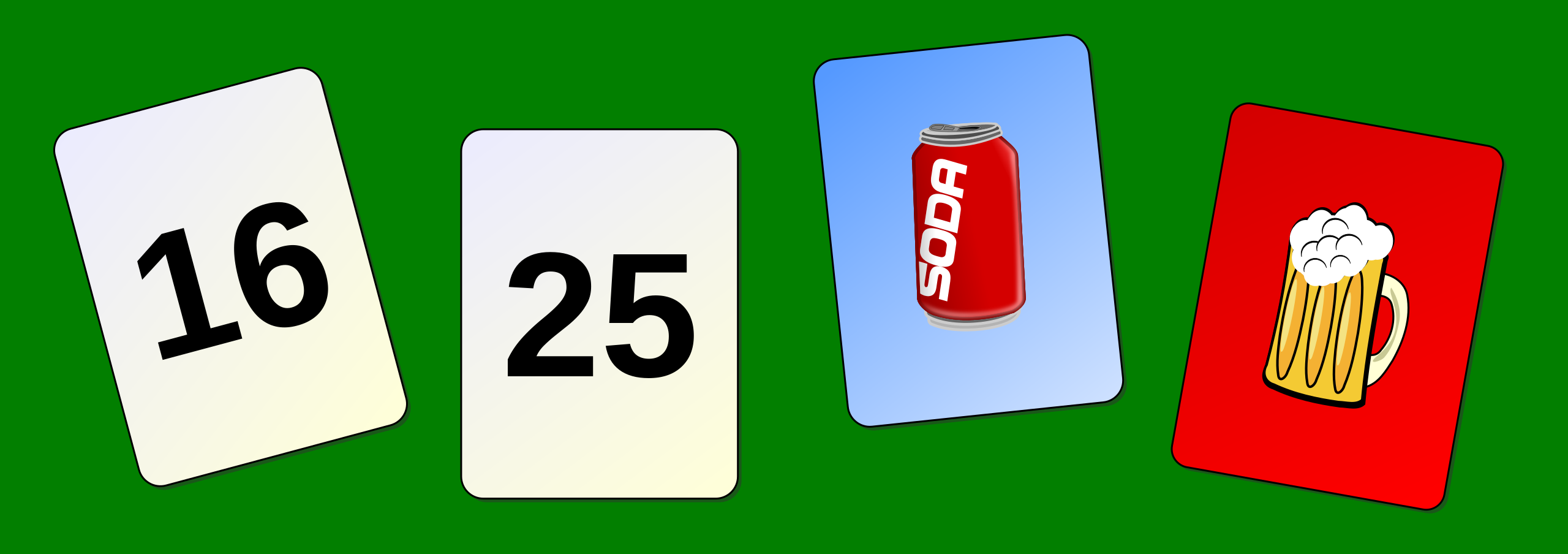

We can make this more concrete with a classic task from the literature: The Wason Selection Task (or sometimes just the Four-Card problem). The scenario posed to participants in this task is something like this: I've got four cards with numbers on one side, and solid colors on the other (let's say they can be either orange or red). I'm going to tell you something that I assert is a fact about these cards: If a card has an even number on the front, then the back of the card is always red. With this assertion in mind, take a look at the cards in the image below - which ones do you have to flip over to see if my assertion is true or not?

Pretty much everybody who takes a look at these decides that they need to flip over the "8" and they're right about that. That card is supposed to be red on the other side, so we better take a look to make sure that's true. But what else should we do, if anything? Here's where confirmation bias tends to catch up with most folks - participants frequently say that they'd like to turn over the red card as well to see if it has an even number on the other side. The trouble with that is that anything we'd discover by turning it over couldn't be a problem for that assertion I started with! So what if there's an odd number there? I never said a thing about the colors that odd cards could have. You know what's nice about the red card, though? It would give us a chance to confirm something that we think is true - we'd have more data that's consistent with our belief about these cards and we have a tendency to go looking for that kind of thing. It's comforting, perhaps, but it's not going to help us work out if our rule is correct. To do that, we've got to be good skeptics and flip over that orange card because that's the one that might provide some counter-evidence for our assertion: If it has an even number, then the rule mustn't be true. In Wason's original work, the vast majority of participants (like 85-90% or so) got the answer wrong in the direction I just described - they were more into confirming their belief rather than subjecting it to strict scrutiny. Lest you think that the four-card problem is too artificial, I'll just say that there is a great deal of excellent work highlighting how people make similar mistakes in a host of realms with real-world decisions to make and much higher stakes. A patient who just arrived in the ER is either having a heart attack or severe indigestion - what should be your next steps to find out more? If the patient looks pretty young to you, you might think that indigestion is more likely and start asking them about when they ate last and whether they had lots of greasy food and send them home if they tell you they just had a Baconator. But y'know what? Checking some enzyme levels would help you rule out the heart attack story, which is potentially what you really ought to do to make a better decision. This is an extreme case, but I hope it highlights how we have to find ways around our cognitive bias to look for information that's consistent with our beliefs rather than information that has the power to make us modify them.

To bring this back to chess, I hope it's obvious what the problem is with regard to my games above: I had some ideas about what my moves were going to do for me and I didn't subject those ideas to appropriate scrutiny! In both cases, I felt like I had a decent position and was thinking about how to bring more pieces to bear down on the enemy King - the Rook I put on d3 in Round 1 and the pawn I moved to b4 in Round 5. Oh, I thought about those moves - they weren't just blitzed out! The trouble is that I looked at them through the lens of my beliefs about that attack I thought I was whipping up: If he pushes his pawn to meet my b-pawn, I can do this. If he tries to trap my rook in the center, I can do this to get away and keep the pressure up. These thoughts and the lines I tried to calculate as a result? That's just me flipping a bunch of red cards over while there's an orange card sitting right in front of me with a minor piece blunder on the other side.

So what can we do about any of this? There are some interesting results in the decision-making literature that suggest there are ways around this particular type of confirmation bias, so all hope is not lost. I'll tell you about two of them, even though I think only one of them has a meaningful connection to chess.

First, the one that's kind of a stretch in terms of it's chess applicability: While the four-card problem (and judgments like it) are decisions we tend to be bad at in the form I described above, recasting them as more socially-oriented problems improves performance a ton. In particular, if we can present the problem in a format that is more like what is sometimes called "cheater detection," participants tend to do much better at deciding what to do. Let's try another four-card problem that's been recast this way: Instead of the odd/even + red/orange judgment I mentioned before, I want to give you a scenario that's much more like real life. You're the bouncer at a bar and you've been asked to make sure that there's no underage drinking going on - specifically, your manager reminds you that "If they're drinking alcohol, they better be 21 years or older." You checked IDs earlier in the night when people came in, so you remember the age of some of the patrons and you can also see what some people are drinking. The data you have available as a result is summed up by the cards below - age is on one side, and the drink they have is on the other. To make sure everything's OK in the bar, which cards do you need to flip over?

My guess is that you got this one right, and not just because we talked about the original variant up above. Of course you need to see what the underage kid is drinking and of course you need to find out how old the beer drinker is! Who cares how old the soda-drinker is or what the 25-year-old felt like ordering? Now that you've been charged with rooting out any "cheaters" it's a lot easier to think about how to subject your beliefs to the proper level of investigation. Is there a way to do this over the board during a chess game? I'm not so sure, which is why I think this way of overcoming confirmation bias is maybe of limited use if we want to improve our decision-making during a game. Can you recast your own moves or your opponent's in terms of some kind of social paradigm like this that spurs you on to the right kind of information-seeking behavior? I mean, maybe, but it's not obvious to me that there's something easy to do or say about the approach that's likely to stick. On the other hand, there is another simple technique that's been found to improve decision-making outcomes in many real-world scenarios where it's critically important to sidestep confirmation bias.

Babies are incredible little beings, but the first minutes of life can often be quite precarious. Newborns are breathing air for the first time, the temperature is suddenly a good bit colder than they were used to, and they're no longer getting the umbilical support from their Mom that they relied upon. Sometimes this adds up to a newborn that's just mad - my older brother, for example, apparently was so angry about being born that he kept holding his breath until he couldn't anymore, then screamed at everyone because he was mad he had to take another breath. Other times, though, a newborn isn't just mad, but is actually struggling to survive and needs help. But how do you tell? What are the right things to look for and how you make a decision about when to provide oxygen, or check for internal bleeding, or any of the other interventions you might make to save the life of a newborn that needs prompt medical attention? Confirmation bias can be deadly here - if you start with the idea "This baby is probably fine" you'll look for things that confirm that and potentially ignore the data that contradicts the premise. What you need to do instead is make sure you get the information that will actually help you make the right call, your prior beliefs be damned! The cognitive augmentation that helps us do that in this setting is such a wonderful and simple thing - it's a checklist.

Specifically, it's called the APGAR test (Developed by Dr. Virginia Apgar, MD) and you've very likely heard of it. Instead of relying on your intuition about how this baby seems to you and what that implies about what you should do next, the APGAR score is a 5-item list of things to check and score very coarsely: Skin color, Pulse, Muscle Tone, Respiratory Effort, and Reflex Grimacing. You get a 0, 1 or 2 on each one and a low number translates into supportive care. The list forces you to just go find out what you need to know and don't let yourself settle for the comfortable data foraging that will prove to you that you were right all along. It may sound silly to call this a cognitive augmentation device, but I think it counts! You're outsourcing the information-gathering process to something external - in this case, the list - which saves you from putting in cognitive work that's likely going to be subject to bias. Checklists like this are fairly widespread in a lot of medical settings, in part due to some very nice work by Tversky and Redelmeier examining decision making and diagnosis in clinical care. Though it's a simple tool, it's a powerful one that frees you from deciding how to decide and should help you get the data that will actually guide a better decision.

Back to chess then, armed with a simple piece of applied cognition: We can use lists to minimize confirmation bias! If you too are a GothamChess fan, you may know where this is going because it turns out that this whole discussion of how to avoid confirmation bias through checklists intersects with a wonderful nugget of advice that Levy frequently advises his viewers to repeat like a mantra.

image

Motivational poster for sub-900 players by PaulRandsGhost - found on Reddit.

It's a checklist, folks, and it's one I should have written down on my scoresheet instead of the words SLOW DOWN. Not that those are bad words to repeat to oneself during tournament play, but the list above is a small set of concrete things to go looking for, both for yourself and for your opponent, that you can coarsely score just like the Apgar test and use to accept or reject candidate moves. It turns a potentially biased, intuitive analysis of a position ("I've got a decent attack, right?") into something very direct that keeps you focused on finding out what problems there may be with a move ("Can they take anything? I don't see how unless theyOH NO THE PONY!") I had this rattling around in my head after binge-watching more "Guess the Elo" than is probably good for me, but it wasn't until my own abandoned pieces affected my tournament score that I realized how much this was a good evidence-based approach rooted in cognitive principles I know. Lesson learned, I suppose - now I'm making stickers with this printed on 'em to slap on all my scoresheets for the next tournament.

I should close by saying that the point of this post was to talk about and think about the mistakes I made (and will probably continue to make for some time!), but the tournament wasn't actually dominated by blunders for me. I had a decent day of it, all told - I won my games in Round 2, 3, and 4, the last two of those against opponents rated near or above 1300. For a guy who walked in with a 1078 rating this felt pretty good and probably translates into something like a 150-point gain. My estimated performance ELO for the day was also just over 1400, which is a really nice confidence booster as well. I don't want to bore you by dwelling on the details of my wins (tempting though this may be), but in the interests of completeness I've put these below for you to check out if you're so inclined. Whether you go look at 'em or not, I hope this was an interesting look at how some basic cognitive science intersects with the things that actually happen during play.

Here's my Round 2 game - My opponent (W) is unrated, and I have the Black pieces.

In Round 3, I played with the White pieces and my opponent (1290) played Black.

In Round 4 my opponent (1308) played White, and I played Black.

You may also like

NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess: What does it mean to have a "chess personality?"

What kind of player are you? How do we tell? NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess - Spatial Cognition and Calculation

How do spatial reasoning abilities impact chess performance? What is spatial cognition anyways? NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess - Eyetracking, board vision, and expertise (Part 1 of 2)

Looking for the best move involves, well...looking. How do players move their eyes during a game and… TheOnoZone

TheOnoZoneObservation Without Judgement

At university I studied petroleum geology. Over the course of those four years of study, I developed… NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess - How visual crowding can hide what's right in front of you.

The limits of your visual system can get in the way of reading board positions. Here's how. NDpatzer

NDpatzer