Why Masters Crush Lower-Rated Players (and You Struggle)

Hint: The secret isn’t a high ceilingSince March 2025, I’ve played in nine tournaments. Across those events I faced lower-rated opponents in 29 games, finishing with a score of 26 wins, 3 draws, and 0 losses. That’s not a flex, it’s just the reality of what being a titled player demands. If you want to climb higher in the chess world then you must consistently take care of business against those below you on the rating ladder.

I know many players, even ambitious ones, struggle here. They play well against peers or even higher-rated opponents, but when paired against someone 200–300 points lower, they get careless, underestimate their opponent, or simply don’t bring the same level of focus. This happened to me plenty of times in the past.

So what made the difference in these recent 29 games? Why was I able to score so heavily and avoid the dreaded upset? It comes down to three main reasons, and one bonus one I’ll admit up front.

1. Good Opening Preparation and Understanding

One of the biggest edges a master has over a lower-rated player is starting the game on the right foot. In those 29 games, I consistently came out of the opening with comfortable, often better, positions regardless of whether I was White or Black.

That doesn’t mean I memorized hundreds of moves and tricked my opponents into traps. It means I had a solid repertoire, tuned for practicality, where I understand the plans and ideas rather than just raw move orders.

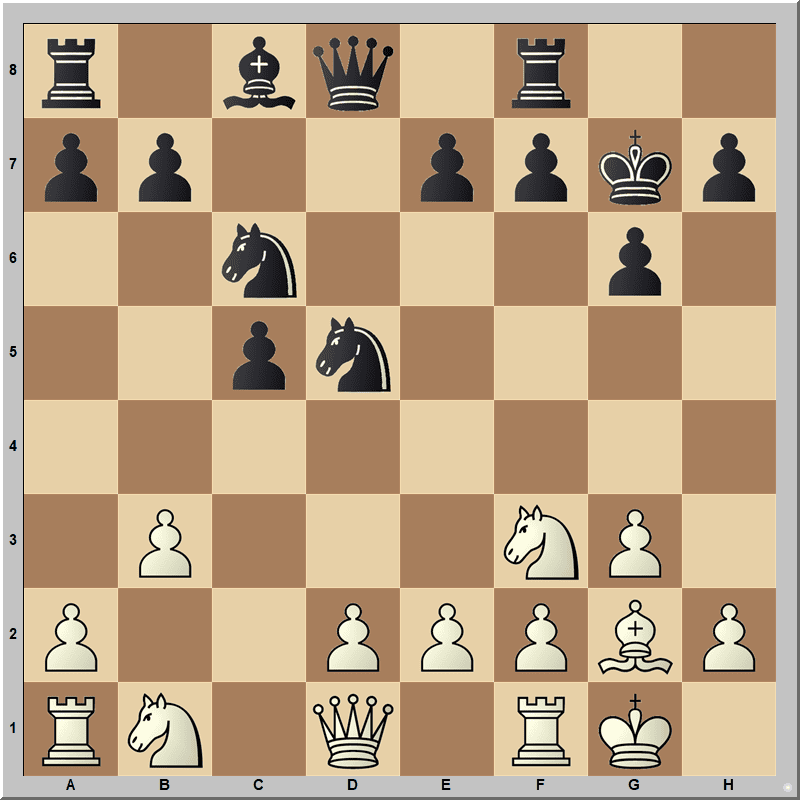

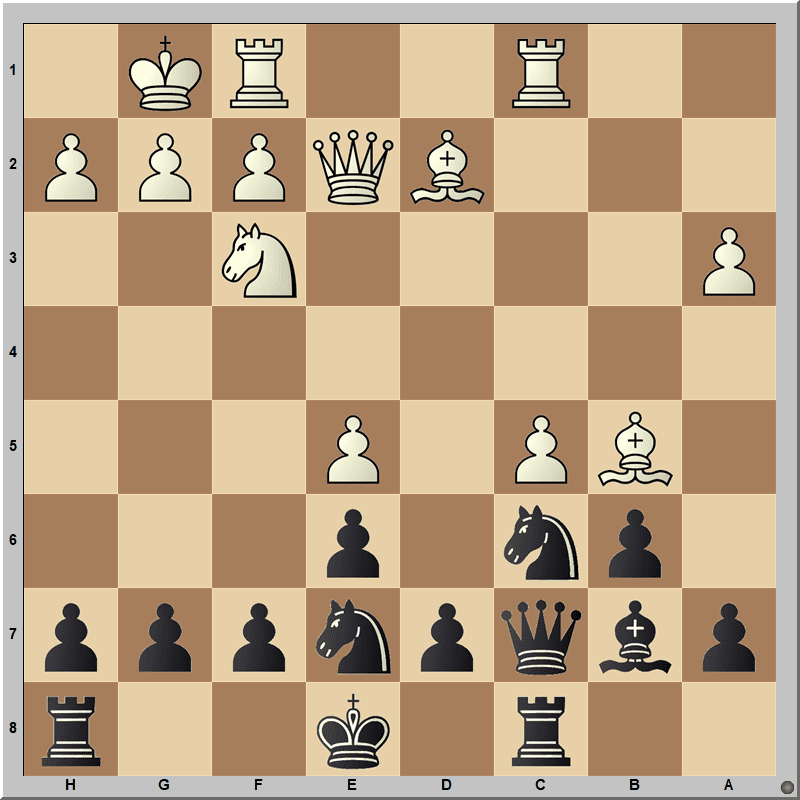

I actually had this exact position in two different games against two different lower-rated players and both of them happened to go the same way. I began with 10. d4 to trade pawns in the center. After 10...cxd4 11. Nxd4 Nxd4 12. Qxd4+ Nf6 13. Qe5! we avoid a trade of queens and Black has a hard time developing their queenside due to the pressure from our queen and bishop. After 13...Qb6 14. Nc3 Be6 15. Na4! we are already going to win material since Black cannot hold onto the b7-pawn for long. After 15...Qb4 16. Nc5 Black cannot defend against the threats on b7, e6 and e7 (behind the bishop).

How did I know about this sequence of moves? From previous opening study and a lot of repetitions in online blitz games:

As you can see in the screenshot above, I’ve already played 10. d4 in this position 42 times in past online games and 32 of these games reached the same position after 13. Qe5!

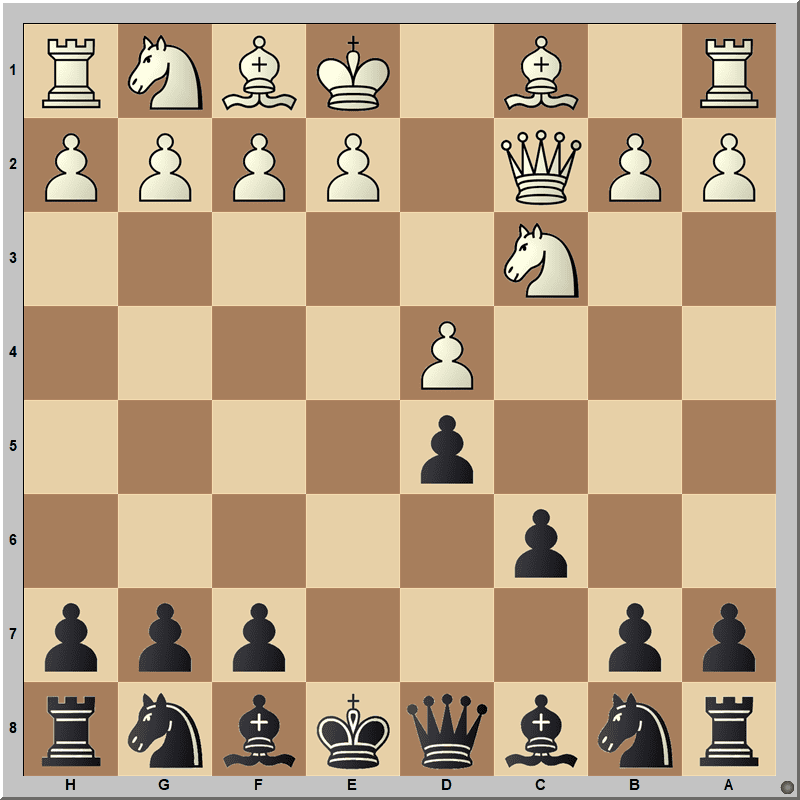

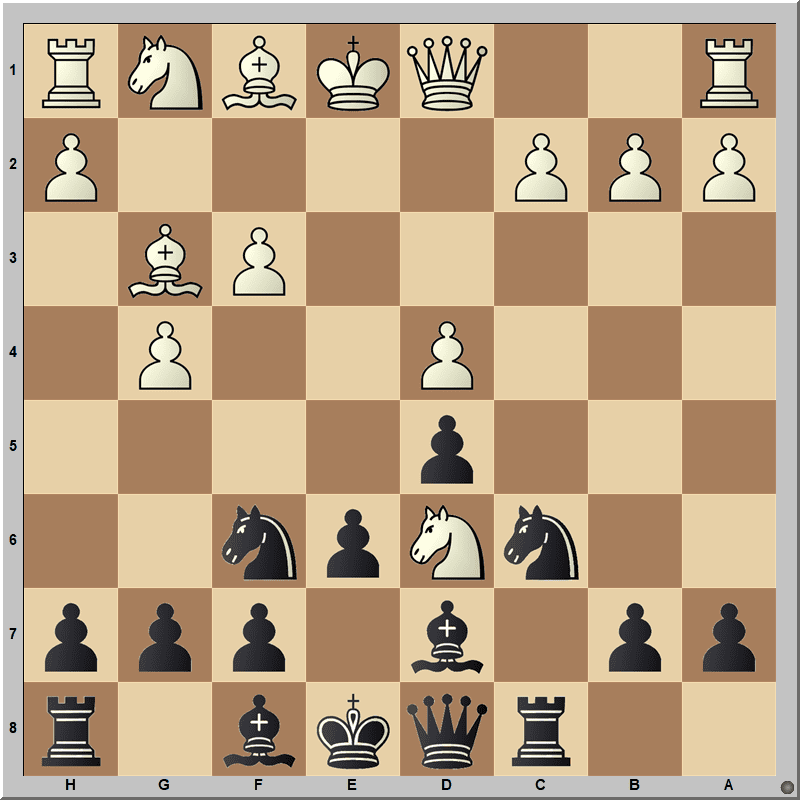

The above position came from a Queen’s Gambit Declined where White traded pawns on d5 before I played ...Nf6. This is typically an earlier pawn trade than they should go for because now their dark-square bishop can lack squares to develop to (since I am keeping it off g5 for now). Because of this, I played 5...Bd6! (controlling f4) 6. Nf3 (he hopes to play Bg5) 6...h6! which completely restricts white’s c1-bishop from developing since both the g5 and f4-squares are covered. After 7. e3 the queenside bishop is closed in and had to develop to the b2-square later which is less than ideal. We have a Carlsbad structure on the board now but it’s a bad version for White since their queenside bishop never got in the game. Let’s compare this to the following position:

Now we’re playing the White side of a Caro-Kann exchange (another position I played in a game against a lower-rated player). Let’s use a similar idea as we saw in the previous position: 4. Bd3 (keeping black’s bishop off the f5-square) 4...Nf6 (hoping to play ...Bg4) 5. h3 Nc6 6. c3 (notice a familiar pawn structure?) 6...e6 and now the queenside bishop is blocked in once again. We end up in another Carlsbad structure where the queenside bishop didn’t get in the game. In both positions, the next plan is to play ...Nf6-e4 or Nf3-e5 and attack the opponent’s kingside. I executed this plan and later won both games.

For each of these positions, I didn’t just know the theory. I knew which pawn structures to aim for, what pieces to trade, and where my long-term advantages lay. By the time my opponent was “on their own,” they were already navigating a worse position without realizing it.

If you want to avoid slipping against lower-rated players, your openings need to be more than memorization. They need to be weapons where you are able to consistently get structures you understand deeply enough that you’re always the one asking questions.

2. Strong Calculation and Punishing Mistakes

At the master level, calculation is second nature. I don’t mean calculating ten moves deep in every position. I mean being sharp enough to spot tactics when they appear, to recognize when the opponent’s move leaves something hanging and to punish hesitation.

Lower-rated players make mistakes. That’s inevitable. The difference between a master and a 1900 is not that the master’s opponents never play well. It’s that the master spots and seizes on the cracks the moment they appear.

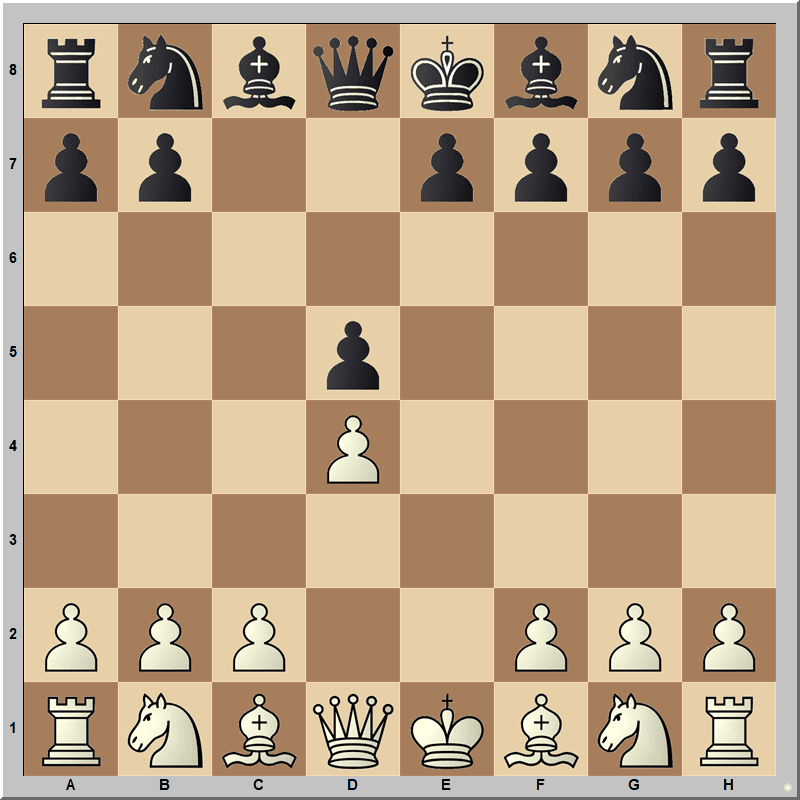

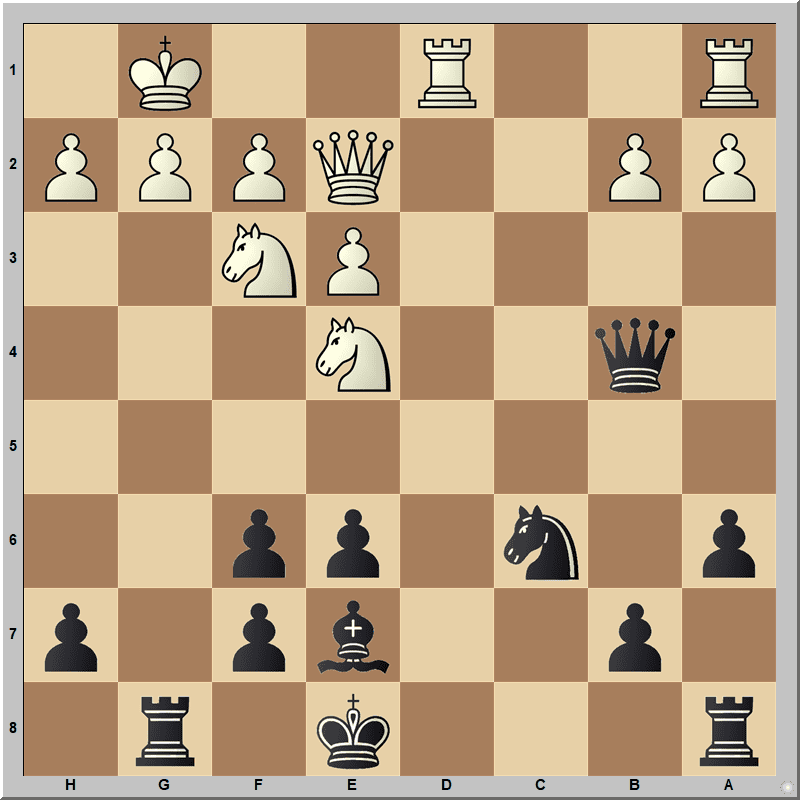

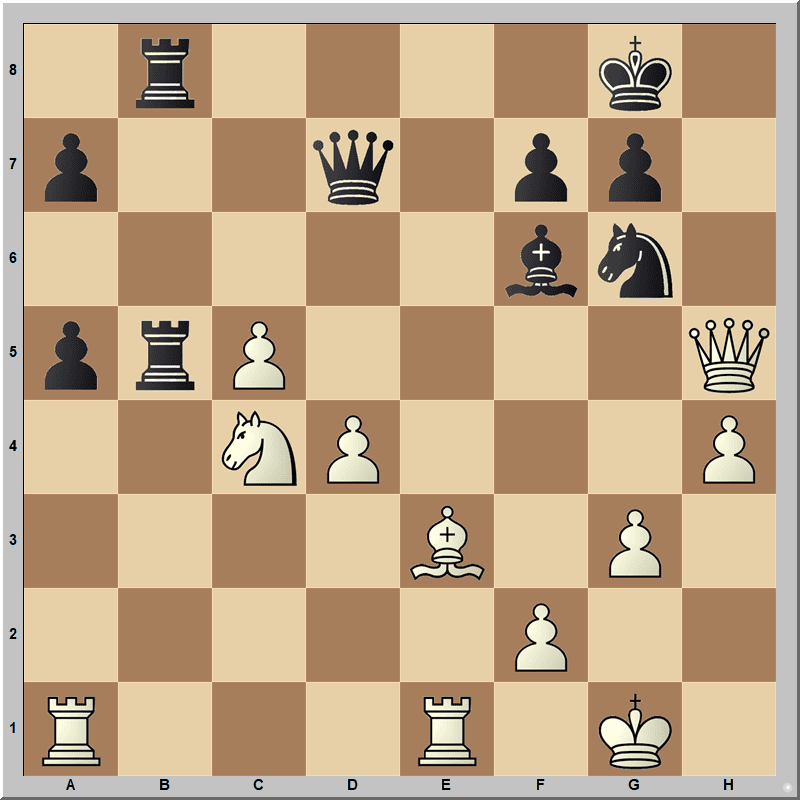

In one of my games from this stretch we find ourselves in the following position:

We have more pieces active in the game but things are a bit awkward for us. Our e6-rook is pinned to our king and White is threatening both Ng5 and Nxc5 or Qxc5 winning material. We cannot capture the knight on e4 with our bishop since our rook would then be left undefended. How do we deal with all of these threats?

Well, one way of doing things is to play 19...Qc6 which pretty much forces 20. Qxc6 Rxc6 and despite having an isolated e-pawn, our position is better due to our bishop pair and active pieces. However, we can do better than this! During the game I calculated the sequence 19...Rd8! 20. Qxc5 Qxc5+ 21. Nxc5 Re2! and surprisingly, White is in a weird middlegame zugzwang with no good moves available. If the knight moves then we can play ...Be4 to attack the g2-pawn while none of the other pieces can move either. The game continued 22. Rf2 Rd1+ 23. Rf1 Rd5 and White is going to lose material since White cannot keep the knight on the c5-square. As soon as it moves, then we can play ...Be4 and white’s kingside collapses. My opponent resigned five moves later.

In another position, my opponent just pushed their pawn to c5, trying to trade off their isolated c4-pawn and open the c-file. However, this is a mistake due to 15...bxc5 16. Rxc5 Nd4! and the tactics work in our favor due to ...Nxe2 being a check. I won the exchange after 17. Nxd4 Qxc5 and went on to win the game later.

In this game my opponent had played a Jobava London gone wrong. They just checked us with Nd6+ but it was a mistake. Now I have the chance to win a pawn with 10...Bxd6 11. Bxd6 Qb6 when White cannot save both the d4 and b2-pawns at the same time. I won a pawn and later the game without much trouble.

It’s not about brilliance every game. It’s about consistency. By being good at tactics and calculation, you make sure that when your opponent errs, you don’t let them off the hook.

3. Never Giving Up

Not every game against a lower-rated opponent is smooth. Sometimes, they surprise you in the opening. Sometimes, they outplay you in the middlegame. And yes, sometimes, they build up an advantage.

Here’s where another key trait comes in: I don’t give up.

I defend difficult positions stubbornly, forcing my opponents to prove they can actually convert. And the reality is, many lower-rated players can’t. They push too hard, they overextend, or they let the position slip back to equality. Also, many times they are happy with a draw against their higher-rated opponent when they should be pushing for the win instead!

One game in particular stands out:

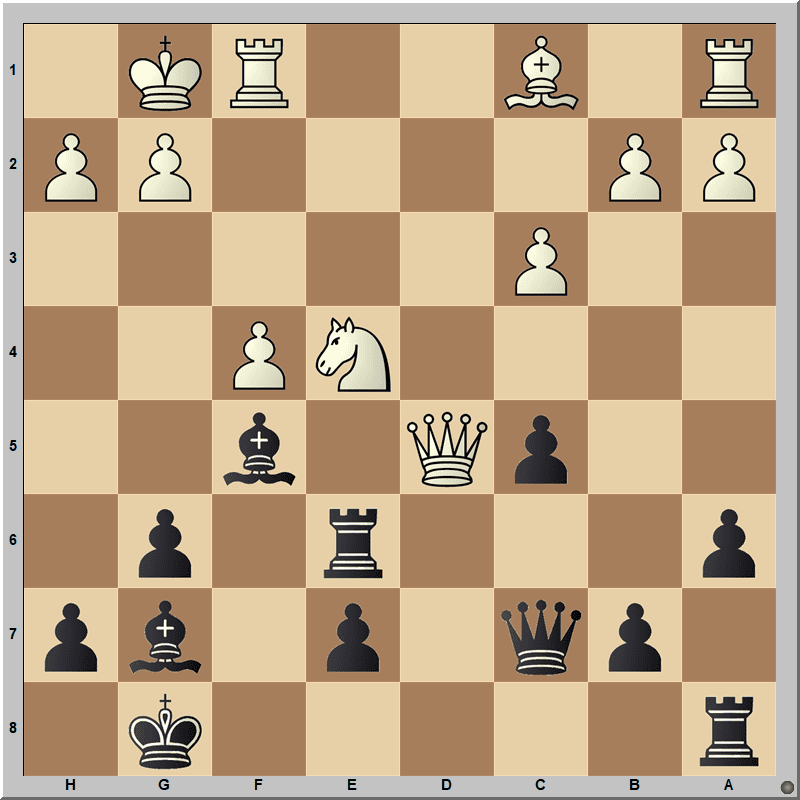

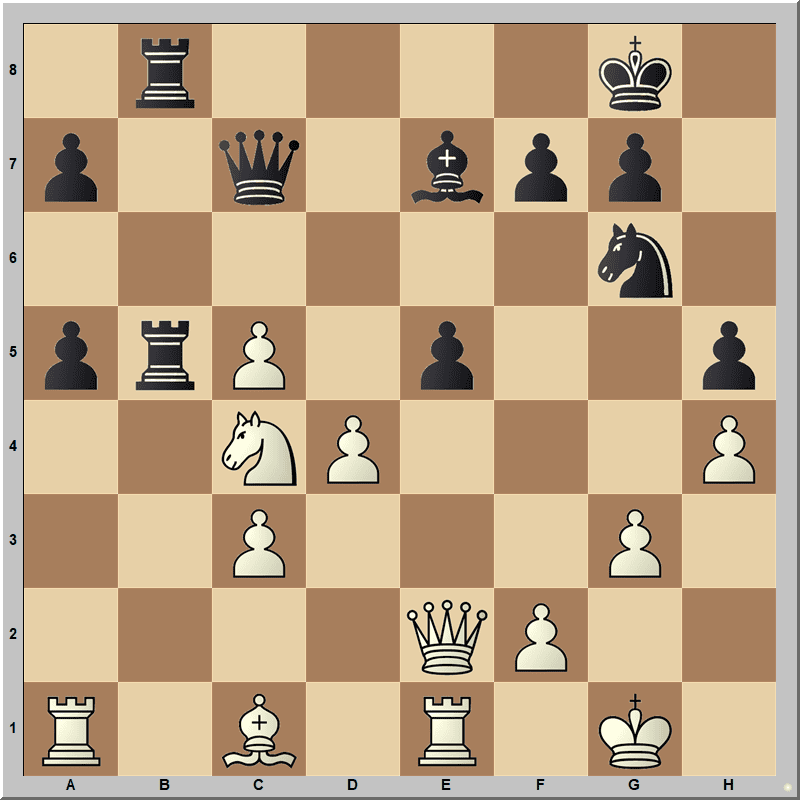

Here it is my opponent’s move and if he plays 16. Ng3! (blocking the g-file) then the computer says he has a +1.5 advantage and is in great shape to work towards winning the game. Instead, he played 16. Nd4?! and I had to dig in to come up with the sequence 16...Rd8! 17. a3 Qb6 18. Qc2?! Nxd4 19. Rxd4 Rxd4 20. exd4 f5 after which the game is much closer to being equal and Black can even argue that they might have a very small advantage. This was one of the three games that I ended up drawing.

Earlier in this game, I had tried to avoid a queen trade in order to keep the game more dynamic but it ended up getting me in a lot of trouble. My opponent had played very well up through this point and had the chance to maintain his advantage. Unfortunately for him, he faltered in the above position and I was able to get back into the game. If I had given up earlier on, then I may not have grabbed the opportunity that was given to me to get back to equal footing.

This mindset of never giving up and never assuming the game is “already lost” is one of the biggest separators between masters and everyone else.

Bonus Reason: Sometimes You Just Get Lucky

Let’s be honest. Sometimes you win because your opponent blunders. Maybe they’re playing great for 35 moves and then, out of nowhere, they hang a piece. I’ve had that happen. Other times, you get lucky that your opponent misses a tactic of their own. You might even completely miss your opponent’s move and get very lucky that you actually do have an available response to that move even though you hadn’t anticipated it at first:

In the above position I have a +6.5 advantage but both my opponent and I are in time trouble. If I simply play 31. Nxe5 then I should coast to winning the game without much trouble. Instead, I made the mistake of playing 31. Qxh5?? exd4 32. cxd4 and got my first lucky break when he didn’t spot the tactic 32...Bxc5! 33. dxc5 Rxc5 when Black would be forking my queen and knight when they are completely back in the game. Instead, he played 32...Qd7? 33. Be3 Bf6

Here I made another terrible time trouble blunder with 34. Nd6?? which my opponent did punish this time with 34...Qxd6! My d6-pawn is pinned along the fifth rank towards my queen!

As soon as he played this, my heart sunk. I had completely missed this fifth-rank pin and was devastated. However, I was very lucky to have the kamikaze response 35. Qxg6! which saves me from being down a full piece. I had definitely not planned that when I played 34. Nd6 but got very lucky here. The game continued 35...Qxd4 36. Bxd4 fxg6 37. Bxf6 gxf6 and I actually still have a slight advantage and went on to win the double-rook endgame later.

It’s important to acknowledge this: luck does play a role in chess. But the key difference is that luck favors the prepared. If you’re defending well, staying sharp, and giving your opponent constant problems to solve, you increase the odds that luck will tip your way.

When I look back on these 29 games, what really stands out to me is the idea of having a high floor. Many players think improvement comes from raising their ceiling, from hitting higher peaks on their best days. But the truth is, when it comes to consistently beating lower-rated opponents, your ceiling matters far less than your floor. My ceiling allows me to play some brilliant games and defeat International Masters or Grandmasters. My floor is what keeps me from ever losing badly to lower-rated players when I’m off form. Even on my worst days, I can still defend, still calculate, and still rely on my understanding of the opening. That’s why I could score 27.5/29 without a single loss.

Players who struggle against lower-rated opposition often have the opposite problem: their good days look incredible, but their bad days look like total collapse. They play for the ceiling and neglect the floor. That’s when the upsets happen.

If you find yourself in that camp, don’t get discouraged. Beating weaker opponents consistently isn’t about discovering some hidden trick that only masters know. It’s about building habits. Work on your openings until you understand them deeply, not just the first ten moves. Train your calculation daily so you can spot mistakes quickly. Practice defending tough positions instead of resigning when things go wrong. And yes, accept that luck will play its part, but also recognize that the harder you work, the more often luck will seem to favor you.

Crushing lower-rated players may not be glamorous, but it’s the foundation of competitive chess. My recent tournament stretch proves that success here doesn’t come from playing like a genius in every game. It comes from preparation, sharpness, resilience, and a bit of luck along the way. If you want to improve, focus less on how high your ceiling can go and more on raising your floor. Become tougher to beat on your worst days. That’s how you’ll turn the games you “should” win into games you actually do win. That, more than anything, is the difference between a master and everyone else.

Don’t just read about improvement—experience it. Work with me at https://nextlevelchesscoaching.com

You may also like

thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. FM MattyDPerrine

FM MattyDPerrineThe 15 Most Influential Books I Read Before Becoming a Master

Reflecting on my chess library CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… FM CheckRaiseMate

FM CheckRaiseMateA Strategic Rule I've Never Seen Before

How do you choose which piece to use for defense? ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… FM MattyDPerrine

FM MattyDPerrine