educationcorner.com

Spaced Repetition

How to get the most out of this powerful memory techniqueRemember when I wrote that post about memory? Well, I forgot to mention the hottest memory technique in chess: spaced repetition. Depending on who you ask, spaced repetition is either the key to learning everything, or a crutch that leads to shallow understanding. So let’s dive into spaced repetition: how does it work, and how can you use it to get better at chess?

What is spaced repetition?

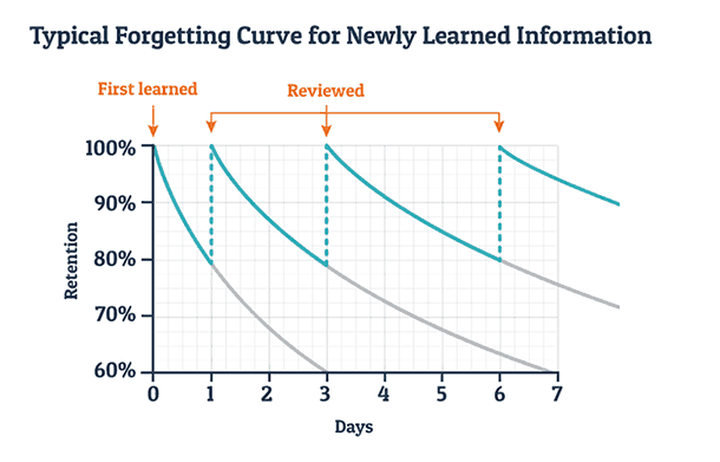

As soon as you learn something, you start forgetting it. The idea of spaced repetition (also called spaced repetition system, or SRS) is that the ideal time to review a piece of information would be just before you forget it. This allows you to build solid long-term memory while investing the minimum amount of time. Every time you review something, you remember it for longer, so you can space out the review sessions over time.

source: educationcorner.com

Spaced repetition has several advantages:

- Each review is short and you can quickly start to space out the reviews over time, so the total time required to commit any piece of information to memory is surprisingly low.

- You get to choose what you remember. Rather than leaving it up to chance which pieces of information you retain and which you forget, once you have a spaced repetition system in place, you can add anything you want and let the system work its magic.

Of course, once you have more than a couple of pieces of information in circulation, it won’t be practical to manage your review cycle manually. You’ll need a tool to automate it.

Tools for using spaced repetition with chess

- Chessable. This is the obvious place to start, since applying spaced repetition to chess is literally the core idea of Chessable’s whole business. Since the platform is purpose-built for chess, you get lots of nice features, like reviewing on an interactive board, engine analysis, etc. There’s also a huge library of courses by top chess players and authors to choose from. My only issue with Chessable from a spaced repetition perspective is that it’s not as easy to create and update your own material as I’d like.

- Chessbook. This is an intriguing newer app. Currently it only supports openings, not tactics or other areas of chess. The thing I like about it is that it offers a smooth and intuitive process for building and reviewing your own opening repertoire.

- Anki. Anki is a general purpose notecard system, not a chess app. This gives you the flexibility to include any kind of information you want – for example, some cards could be images of chess positions where you have to find the best moves, others could be questions to answer, and so on. But you won’t get chess-specific features like an interactive board. Anki gives you a lot of control over details like your spaced repetition schedule, but also takes more work to set up. This could be a good choice if you are the DIY type who likes to fiddle with all the details, or you want to experiment with different types of cards.

- Actual physical notecards. Not as crazy as it sounds! Neal Bruce is known for buying two copies of every chess book: one to read and one to cut out diagrams for notecards. If you are the sort of person who prefers physical copies of books over Kindle, this might be a good option for you. I recently learned about a system for kids’ vocabulary words that would work equally well for chess. You start with all your cards in a “to-do” pile. Each time you review a card, if you get it right, you put it in a “done” pile, but if you get it wrong you shuffle it back into the “to-do” pile. Over time you gradually add more cards. When all the cards are in the “done” pile, it becomes the “to-do” pile and you start all over. This system is extremely simple but still incorporates the main elements of spaced repetition. You review cards more often if you get them wrong, and as your deck grows over time, the frequency with which you review old cards decreases.

Applying spaced repetition to chess

Which parts of chess does spaced repetition make sense for?

The obvious one is openings. There are a lot of opening variations to remember and without a system like spaced repetition, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to keep everything straight in your head. Some people advise against memorizing openings, but I don’t think memorization is inherently bad. The problem is memorizing excessive or irrelevant lines. You should make your repertoire as compact as possible, but having done that, it makes sense to memorize the key lines. And spaced repetition is a very efficient system for doing this.

You can also use spaced repetition for tactics. Some players have had good results with this. For example, Alex Crompton went from 300 to 1500 in nine months using spaced repetition of tactics courses on Chessable as the backbone of his training plan. This can definitely work, but there is also an appealing alternative: training tactics on Chess.com, Lichess, or from a puzzle book. The main difference would be that with spaced repetition you will be seeing the same positions repeatedly, whereas with puzzle training you’ll see a steady stream of new positions (although both sites do allow you to review your past mistakes). I’m not convinced there’s any particular benefit to doing the same positions repeatedly, but I also don’t think there’s anything wrong with it. The important thing is to practice tactics daily, so go for whatever system allows you to do that.

You might have noticed that this is quite similar to the Woodpecker Method, which also advocates for training the same tactics repeatedly. The difference is that whereas with spaced repetition you review the same material at increasing intervals, in the Woodpecker Method you review them at decreasing intervals. This may be a bit less sound pedagogically, but again, as long as you’re working on tactics every day you’ll be fine.

One other use for spaced repetition that is less common, but potentially highly effective, is reviewing your mistakes. It seems logical that mistakes you make in real games are likely to reveal gaps in your understanding, which you could shore up with consistent review. I’ve used this method at various times, saving positions where I made a mistake. Some of the positions are missed tactics that would make good puzzles, but others are strategic ideas, defensive moves, or other sorts of position. What I’m really looking for are positions that are emblematic of some sort of pattern or area of the game that I’m trying to improve. Here’s a position from a student game that would make a good flashcard.

Here White played Bg5, which was certainly a reasonable move, but e5 would have been immediately crushing. If the knight moves, White has Bxh7+ with a winning Greek Gift sacrifice. Most books would not give this position as a puzzle because according to the computer White has many moves to maintain a big advantage, but it makes a good flashcard. It’s good practice for the Greek Gift pattern, and it’s emblematic of sensing the right moment to pounce with a direct attack. You want to get to the point where patterns like this jump off the board at you.

In addition to selecting these positions manually, it’s also possible to automatically retry your mistakes using Chessable Connect. I actually worked on this feature when I was working for Chessable!

Going beyond spaced repetition

Does spaced repetition actually work? Yes, there is a lot of evidence for this from language research and elsewhere. It definitely works. And if you’ve never tried this technique before, I think you’ll be surprised by how effective it is. If anything, the problem with spaced repetition is that it works too well, which makes it tempting to see it as an all-purpose learning solution. But the truth is that it works for some things better than others.

Spaced repetition is very effective for discrete bits of knowledge that are easy to isolate and define, like vocabulary words or opening variations. It’s less effective for more abstract types of knowledge, like how to write a compelling paragraph or how to play a certain middlegame structure. The real question for chess players is how much of what really counts for chess success can be encapsulated in this format. At the same time, you should keep in mind that memorization and understanding are not opposed, but complementary. Memorizing the important things that can be memorized frees up mental bandwidth to focus on more challenging things.

I don’t know the exact percentage, but it’s pretty clear that there are some parts of chess that work well with spaced repetition and others that don’t. For this reason, spaced repetition is best seen as one tool in the toolbox, not the whole toolbox. I’ll leave you with three other tools you can use alongside spaced repetition to strengthen your memory of key concepts:

- Learn the same idea from a different source. If you just watched a YouTube video on an opening, try watching another video on the same opening from a different creator. Seeing what ideas they have in common and where they differ will give you a deeper understanding of the material.

- Free recall. This means recreating as much as possible of what you’ve learned with no cues. If you’re learning an opening, open an empty file and enter in as many lines as you can from memory. Or if you watched a video recap of a classic game, the next day, see if you can reconstruct the game from memory. Practicing recall will make your memory much stronger.

- Teach a friend. After you learn something, try teaching it to someone else. When you’re forced to explain something, it often reveals gaps in your knowledge that you weren’t aware of. And your friend may ask questions you hadn’t thought of.

If you liked this check out my newsletter where I write weekly posts about chess, learning, and data: https://zwischenzug.substack.com/

You may also like

FM CheckRaiseMate

FM CheckRaiseMateCreativity in Training

Ideas from two very different adult improvers FM CheckRaiseMate

FM CheckRaiseMateWorkout of the Week

A chess puzzle to get your brain sweating GM NoelStuder

GM NoelStuderHow To Remember Chess Moves And Openings

In chess, a lot is about proper memorization. Not only opening lines but important endgames and patt… GM NoelStuder

GM NoelStuderWhy You Should Never Offer A Draw

Offering a draw is the fastest way to lose the possibility to learn. You rate the result higher than… FM CheckRaiseMate

FM CheckRaiseMateThe 100 Games of Blitz Challenge

Transform your chess game in November FM CheckRaiseMate

FM CheckRaiseMate