Triptych by Galina Satonina

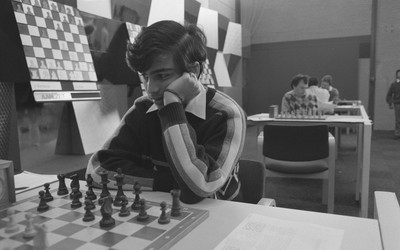

Rashid & Misha: A Series | Part 1

IM Rashid Nezhmetdinov and GM Mikhail Tal are, by any measure, amongst the strongest and most successful players of the 20th Century. They are also two of the most aggressive chess players to have ever lived. Needless to say, both of them are among my (and I would imagine, most people’s) favorite players of all time. I thereby found it worthwhile to examine the 4 games they have played against each other. In this series, I shall attempt to build a profile for each of these players, before proceeding to analyze their games against each other.Note: I am also the primary contributor to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rashid_Nezhmetdinov, so there will be significant overlap between the two. What started as my first blog post turned into a fairly interesting research project, especially considering one of my favourite chess players had a Wiki and chessgames.com profile that was all of two paragraphs. This is also why the post has been delayed by several weeks, but is considerably more detailed than I had originally intended.

Part 1: "No Reverse Gear Rashid"

Born Dec-15-1912, Died Jun-03-1974

Peak Rating: 2455 (January, 1973)

“I must have beaten Rashid a dozen times. But that one loss was so good I would have traded them all to be on the other side of the board” - GM Lev Polugaevsky

Rashid Nezhmetdinov was born in Aktubinsk, part of present-day Kazakhstan into an impoverished family of Tatar farmhands. His parents were “worked to death” when he was still very young, rendering him (and his two siblings) an orphan. Rashid was then sent to live with his uncle, in a small town on the banks of the Volga river. From 1918-1923, the Russian Civil War would devastate the region, particularly with the introduction of the Prodrazvyorstka policy, a system whereby peasant’s foodgrain was confiscated (read: stolen) at nominal prices, as per fixed quotas. The ensuing famine would kill over 2 million children. But Rashid endured, thanks in large part to his poet, brother – Kavi Nadzhmi – who secured him a place at a Kazan orphanage. Rashid would regard this orphanage as paradise, his only prior happy memory being the time he got to eat fish soup on the banks of the Volga. In Kazan, Rashid would be well-fed (for the first time in his life), learn the Tatar language, and be initiated into Islam. During this time, Rashid developed a keen interest in history, literature and mathematics. Three years later, Kavi would be able to bring Rashid into his own home, also at Kazan. Here, Rashid would be thoroughly engaged in the Kazan “Palace of Pioneers,” which marked the beginning of his chess career. This was a social engagement, not unlike modern day boy scouts, but with the added benefit of communist indoctrination.

Rashid was naturally adept at chess and checkers, and was quickly invited to join the Kazan Chess Club. He won his first chess tournament at just 15 years of age, winning every match he played. Rashid also achieved commendable placements in many Russian Checkers Championships (he would eventually give up checkers in favor of chess, famously remarking that all checkers contests can be reduced to rook endgames). It was around this time that Kavi, now a poorly paid newspaper editor, could no longer afford Rashid’s upkeep. Rashid then joined the Communist Party and moved to Ukraine, in the hopes of making his own way in the world. In Odessa, his Communist Party membership would give him good standing – and he worked as a stoker in a steel mill. He would get to spend all his free time playing at the Odessa Chess Club (Trivia- While Odessa did not have any chess masters, it would produce future GM like Efim Geller who was roughly 8 years old at the time).

In 1933, Rashid, now the Odessa Chess and Checkers Champion, and a Category I chess player, would return to Kazan. He secured employment with the Standards Bureau, taught at the local Pedagogical Institute and ran an informal chess circle. Over the next two years, Rashid was primarily concerned with checkers and earned himself title of Master at the game. This was no small feat considering checkers was taken very seriously in the USSR at this time, and frequently reported in chess magazines. However, it was only after receiving (by his own admission!) a “thrashing” from “stronger Category I Chess Players” like Anatoly Ufimtsev and Pyotr Dubinin in 1936, that Rashid began to take chess seriously. Sadly, he would fall ill and be hospitalized for many months immediately thereafter. However, in his characteristically optimistic fashion, Rashid would seize this opportunity to study endgames; typically by solving puzzles without a board. And, in his very next tournament, he would win 9 out of 10 games in his very next Category I tournament in 1939, and earn himself the Candidate Master title. After graduating in 1940, in 1941, he was called to military service, and here his chess development would take a major setback. He was deployed in Baikala, 5000km away, on the border of Mongolia. While Rashid would still compete in district level tournaments, even securing wins against players like Victor Baturinsky and Konstantin Klaman, these appearances were very rare. The War would eventually create a five- and half-year period where Rashid would play no tournaments.

There was a silver lining though – Rashid was actually quite lucky. He always seemed to arrive or leave before an apocalyptic battle. He arrived in Baikala right after the Red Army had fought a brutal battle with Japan’s Kwantung Army. He was then sent to Berlin immediately after the Soviets had stormed it. Rashid successfully avoided every major combat zone in a war that killed over 11 million Soviet soldiers.

And in Berlin, from 1946, Rashid was able to resume his long-interrupted chess career and devoted himself entirely to chess. In 1946, he won Championship of the Berlin Military District, winning 14 out of 15 games, and finishing ahead of future Ukranian Champion, Isaac Lipnitsky.

Later that year, Rashid, now 34-years-old returned to civilian life and his primary occupation was to serve as the Captain of the DSO Spartak chess team. In 1947, Rashid finished in shared second place at the All-Union Candidate Master tournament at Yaroslavl. This marked the beginning of a tumultuous friendship between Rashid, Vitaly Tarasov (the winner), Ratmir Kholmov (shared second).

With this performance, Rashid had also earned his second Master norm. He now had the right to play an examination game for the title of Soviet Master. Georgy Lisitsin was appointed as Rashid’s examiner. However, after studying Lisitsin’s games for many months, Rashid received a telegram from the Soviet Chess Federation, mere days before his match, stating that his examiner would be Vladas Mikenas. Mikenas was, a far more formidable opponent.

In his renewed preparations, Rashid came across an Article written by Mikenas on the Alekhine’s Defense, in Shakhmaty v SSSR, a popular chess magazine of the day. Mikenas claimed it was his preferred response to 1. e4 (Rashid’s favorite first move). This must have been particularly intimidating considering Mikenas had only recently beat the legendary Alexander Alekhine at the 1937 tournament in Kemeri, Latvia, with the black pieces no less!

https://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1004569

Trivia- It is said that Alekhine did not speak to Mikenas for many years after this game. As noted by @muayadali, this win was despite inaccuracies on Mikenas’ part, who could have forced Alekhine to resign as early as move 23.

Nevertheless, the fearless Rashid still played 1. e4 in their first game and, even entered the “Hunt Variation” of the Alekhine Defense; Mikenas’ favorite. He crushed Mikenas in 17 moves. He beat Mikenas again, in the same variation, in Game 11. However, the Game was drawn 7-7 and Rashid did not gain the coveted Master title, because the examiner got draw odds. However, Rashid was not discouraged and this result only reinforced his belief that the title was within his grasp. However, this optimism must have led to a very frustrating few years for Rashid, especially considering how brutally frank he was about his own performance.

His next break through would come in 1950, when he earned the right to play at the prestigious RSFSR Championship at Nizhny Novgorod (this Championship was limited to the Russian Federation and thereby second to the USSR Championship). The competition was fierce, with Masters like Isaac Boleslavsky (the tournament favorite), among many others. Rashid drew his game with Boleslavsky and went on to become the 10th Champion of the Russian Federation. He was finally a Soviet Master.

He returned to Kazan, where a hero’s welcome awaited him. He would go on to win the RSFSR Championship again, in 1951 at Yaroslavl. But his other tournament performances were relatively underwhelming. For instance, at the Baku International in 1964, Rashid could only secure 4 points in 12 rounds; a performance he said owed to his “underestimation” of his opponents. He finished in third place, behind Antoshin and Vladimir Bagirov. It is worth noting that around this time, Rashid, Vitaly and Ratmir had become boisterous drinking buddies. As the story goes, in Baku, they treated their hotel rooms like they were rockstars. Rashid is said to have hurled crockery out the window, and eventually gotten into an argument with Ratmir. Vitaly tried to diffuse the situation, but to no avail. By this time, the commotion had caught the attention of GM Alexander Kotov, an observer on behalf of the Soviet Sports Committee (Trivia - It is widely believed he worked for the KGB). He reported all 3 Masters to the Sports Committee. Ratmir and Vitaly received the worst of it (the reason for this is unclear, but some say its because Rashid was the only Communist Party member among them), with each receiving a 1-year ban from tournaments and having governments stipends suspended. Rashid retained his stipend,and was banned for a shorter period of time (Trivia - Years later, Ratmir would accuse Rashid of “groveling” before the Committee). But all things considered, the 3 Masters were quite lucky. The Soviets had a well-documented history of punishing Chess Masters much more severely, for lesser offences. Some of the more extreme examples include, for instance, the execution of Arwid Kubbel for sending a chess composition to the foreign press. Peter Izmailov, the first Russian Federation Champion, was shot for his alleged involvement in an assassination plot. Similarly, Vladimir Petrov (not to be confused with Alexander Petrov, the proponent of the Petrov Defence – my favorite opening for Black) had been sent to the Gulag for “counter-revolutionary activities.”

This marked a turning point in Rashid’s life and he turned a new leaf. He gave up the “party all night” lifestyle, and married Tamara Ivanovna (little is known about her apart from the fact that she’s the mother of Rashid’s children). It was also around this time that Rashid wrote the first ever chess book in the Tatar language.

Rashid’s next major tournament was the 1953 RSFSR Championship at Saratov, which he won. And in 1954, Rashid finally got to play on the grand stage, the 21st USSR Championship at Kiev – the holy grail of Soviet Chess. This would prove to be Rashid’s toughest competition so far with other masters like Tigran Petrosian and Efim Geller, who were already ranked amongst the best players in the world. Rashid finished the tournament in shared 7th place, but, finishing with 4.5 wins in 7 matches against Grandmasters, is a great achievement in itself.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, Rashid was finally able to play chess internationally. Nikita

Khrushchev adopted a far less repressive regime, pertinently, removing most travel restrictions for sportsmen. It was also around this time that the Russian Sports Committee came under fire from the international press for only ever sending their “strongest Grandmasters” abroad. The idea was for Russia to send 4 of their “mere Masters” to the 1954 international tournament at Bucaresti. Rashid was chosen, along with Semen Furman, Viktor Korchnoi and, his old friend, Ratmir Kholmov. Prior to leaving for the tournament, the four masters were summoned to Moscow, where they underwent rigorous training under Isaac Bolevslavsky and David Bronstein.

This was the first time Rashid had left the USSR, the first time he would face International Masters and the first time he would face non-Soviet Grandmasters. Despite all the pressures, his performance was exemplary.

· Lost to IM Luděk Pachman

· Won against IM Miroslav Filip

· Won against IM Robert Wade

· Won against IM Bogdan Sliwa

· Won against GM Gideon Ståhlberg

· Won against GM Enrico Paoli

Rashid shared the lead with Viktor till the last round, but Viktor ultimately won the tournament. Rashid finished in clear second place. This performance earned Rashid the title of International Master, the highest accolade he would receive in chess.

Here are the final standings for Bucaresti, 1954

| Viktor Korchnoi | 13/17 | (+10 -1 =6) |

| Rashid Nezhmetdinov | 12.5/17 | (+10 -2 =5) |

| Miroslav Filip | 11/17 | (+8 -3 =6) |

| Ratmir Kholmov | 11/17 | (+7 -2 =8) |

| Gyula Kluger | 10.5/17 | (+6 -2 =9) |

| Semyon Furman | 10/17 | (+6 -3 =8) |

| Ludek Pachman | 10/17 | (+6 -3 =8) |

| Alberic O'Kelly de Galway | 9.5/17 | (+4 -2 =11) |

| Gideon Stahlberg | 9/17 | (+5 -4 =8) |

| Octavio Troianescu | 8.5/17 | (+5 -5 =7) |

| Bela Sandor | 8/17 | (+4 -5 =8) |

| Ion Balanel | 7/17 | (+3 -6 =8) |

| Bogdan Sliwa | 7/17 | (+6 -9 =2) |

| Stefan Szabo | 7/17 | (+4 -7 =6) |

| Robert Graham Wade | 6.5/17 | (+4 -8 =5) |

| Victor Ciocaltea | 6/17 | (+3 -8 =6) |

| Enrico Paoli | 3.5/17 | (+1 -11 =5) |

| Paul Voiculescu | 3/17 | (+0 -11 =6) |

Trivia - Nezhmetdinov won the tournament first brilliancy prize with his astounding win against Paoli in the fifth round. Just before the fifth round, Nezhmetdinov was informed that his son, Iskander, had just been born. He was later quoted as saying "At the end of the round, I sent a telegram to my wife: 'I congratulate you on the birth of our son, and I dedicate my game with Paoli to him.'"

Rashid’s next major tournament was in 1954, the 24th USSR Championship in Moscow. While Rashid would only finish in 13th place, he distinguished himself with stellar wins against two future world champions –Mikhail Tal and Boris Spassky. (Trivia- Tal would go on to win the tournament and become the youngest USSR Champion in history).

Despite this commendable performance, Rashid was terribly disappointed with his gameplay. He thought he was able to “carry creative lines of thought to their conclusion” only in “isolated games,” and usually had “painful collapses” instead. Given his mental state, the heartbreaking news he received upon returning to Kazan could have only made things worse – his brother, Kavi, now a prominent Tatar author, had passed away. Later that year, he was awarded a government medal for his contribution to “Chess Art,” a laurel he was most happy to receive.

In 1957, Rashid won the RFSFR Championship at Krasnodar for an unprecedented fourth time. He would later win it again in 1958, at Sochi, for the fifth and final time. It was at Sochi that he played his “Immortal Game” against Lev Polugaevsky, considered by many to be the greatest chess game ever played.

https://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1111459

Trivia – Polugaevsky later famously said “I understand I was to say goodbye to all hope, and that I was losing a game that would be spread all over the world.” As he had feared, a painting was commissioned depicting the two players and “the board of destiny.”

Rashid’s next tournament would be the 1958 USSR Team Championship at Vilnius, where he served as Captain of his team – RSFSR. They finished in 3rd place, among the 9 teams at the competition. By now it was 1959, and a 46-year-old Rashid was finally feeling the effects of age, only accentuated by his former, hard-living lifestyle. He notes in his autobiography that he was the oldest participant at the opening ceremony of the 1959 USSR Championship in Tibilisi. But his legendary win against Bronstein with the white pieces must have offered him some consolation. In 1961, he would finished 2nd at the Chigorin Memorial Tournament at Rostov on Don, behind only Mark Taimanov

These years (1959-61) involve a stint with Tal, that features several interesting anecdotes. I’ve saved these for Part 3 of this Series, where I also analyze their games against each other.

And then, in 1961, Rashid would then try to win the prestigious RSFSR Championship at Omsk for a record sixth time! Here, things got off to a rocky start, and Rashid would finally find himself in a group of 5, tied for second place, behind Lev Polugaevsky. A clear second had to be chosen since the top two players would get a chance to play in the next USSR Championship. Nezhmetdinov triumphed, winning the tie-break and finishing ahead of Vladimir Antoshin and Anatoly Lein. And with that, Rashid would play at the 29th USSR Championship in Baku, 1961. Unfortunately, Rashid only secure 19th place; but won many notable games. This tournament also features his 3rd game against Mikhail Tal, again, covered in great detail in Part 3.

The next decade would mark a particularly uninteresting period of Rashid’s life. In 1961, he would compete in his fifth USSR championship at Kharkov. The competition was diluted as over 120 players were invited, in a bid to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the October Revolution. Rashid would still only finish in 27th place, a position he shared with 14 other players. His next tournament, almost 12 years later, would be the 1973 Latvian Open at Daugavpils. But, a 70-year-old Rashid would fall ill during the tournament, and not even finish his last game. He finished in 3rd place; far below his potential.

In his last few years, he coached the Kazan Chess team at the Old City Chess Club and regularly gave simultaneous exhibitions in his hometown. He was said to be an approachable and joyful man, who was always ready to discuss anything under the sun; especially chess! Rashid passed away in the Summer of 1974.

Many people don’t know that Misha and Rashid were actually close friends (as I’ve hinted several times in this post), something I plan to discuss in Part 3 of this series. Till then, I leave you with this pulchritudinous note Misha left in his obituary.

“I am both sad and pleased that in his last tournament, Rashid came to my home in Latvia. He did not take first place, but the prize for beauty, as always, he took with him. Players die, tournaments are forgotten, but the works of great artists are left behind to live on forever.”

Grandmasters on Rashid

“He was, to the highest degree, a Grandmaster of chess beauty” – GM Max Euwe

"the greatest master of the initiative" – GM Lev Polugaevsky

"... he thrice defeated Mikhail Tal and would wipe the floor with many contemporary grandmasters" – GM Nigel Short

“Nobody understands combinations like Nezhmetdinov” – GM Mikhail Botvinnik

Fun anecdotes involving Rashid

- Three Days with Bobby Fischer and Other Chess Essays by Lev Alburt

As the story goes, Alexey Suetin, a promising young talent, was set to play in one of his first invitational Soviet tournaments. Since he was not very well unknown in the USSR at that time, he was provided with an old Belorussian master, a noted opening theoretician, as a second (lot like a trainer).

In Game 1, Suetin was to play the black pieces against Semyen Furman. The trainer said no preparation was required since the game would take a predictable course. Furman would open with the queen’s pawn, gain an advantage and keep pressuring Suetin. Suetin was disappointed by his second’s lack of help and confidence and was even more distressed when the game proceeded as predicted (Unfortunately, this game doesn’t seem to be available online).

In Game 2, Suetin was to play the white pieces against Nezhmetdinov. Again, the trainer said no preparation was required. “Why not?” “Well, color won’t matter. Nezhmetdinov can play any opening. Somewhere he will sacrifice a pawn for the initiative. Then he will sacrifice another. Then he will sacrifice a piece for an attack. Then he’ll probably sacrifice another piece to drive your king into the center. Then he will checkmate you.” Suetin was upset. “What kind of help was this?” He went to the game, and the old trainer’s prediction again came true.

Now Suetin was very upset. He called the Belorussian sports ministry, telling them that they must recall this fatalistic fellow immediately. The shocked trainer was sent back to Minsk, where he walked around the chess club complaining of his unfair treatment.

“‘I don’t understand why this young Alexey is so upset with me,’ the trainer would say. ‘Everything I told him turned out to be exactly right!’”

- Smart Chip from St. Petersburg and other tales of a bygone chess era by Genna Sosonko

"Once Mikhail Tal offered me to play 'a couple of speed games' in his hotel room. When I knocked, there was a tall middle-aged man whom I did not know. He said: 'Misha is away on some business, but he will be back soon, and asked me to let you in. Please, wait here, if you don't mind. We could play some blitz, too.' I knew that Misha sometimes travels with his uncle Robert, so I thought it was he. Of course I stayed, and generously (so I thought) accepted the invitation to play to pass the time.

I was crushed in the first game, in which I did not pay much attention, but when I lost four more games, I almost began to panic. It was very rare for me to lose in such style, going down in flames like the Russian ironclad in Tsusima in 1905. I could accept being crushed by Tal himself - but his uncle?“

Further Questions

Why did Rashid never become a GM?

There are few schools of thought on this. The first, believes that Rashid was obsessed with attack, and played for tactics and complications, even when there weren’t any. Accordingly, they believe it was his ineptitude for defence that led to him never receiving the title. This is perhaps best summed up by the following quote from Averbak

Others believe he was discriminated against because he was a msulim (tatar) and therefore given less chances to go abroad

Korchnoi remembers Nezhmetdinov: "I played my first tournament after my marriage in Sochi. This was the Russian SFSR championship, and it was won by Nezhmetdinov, one of the strongest Soviet masters. For some reason, he was very rarely allowed to go abroad, and, obviously, he never became a grandmaster because of that.

The most popular answer is simply because he did not play enough tournaments. As a consequence of living behind the “iron curtain” for many decades, he only left the USSR a total of 3 times. But, perhaps the best argument is the one advanced by popular chess blogger, Spektrowski.

“ Let us also consider the other Soviet Players who became GMs around the time Rashid should (emphasis added) become one.

1954 - nobody.

1955 - one player, Boris Spassky. He won the youth world chess championship and qualified for the Interzonal, where he got his grandmaster's norm. Boris was very lucky. The world championship in Antwerp ended on 8th August, and the Interzonal, which, luckily, was held in Gothenburg, began in a week - on 15th August. And Spassky got there in time, which, considering the Soviet bureaucracy of the time, was quite a feat.

1956 - again just one player, Viktor Korchnoi, by accumulated results.

1957 - only one player again, Mikhail Tal. He won the Soviet championship.

In 1958 and 1959, no Soviet players became grandmasters.

So, in six years, from 1954 to 1959, only three Soviet players became grandmasters: Spassky, Tal and Korchnoi. How was Nezhmetdinov supposed to become a grandmaster if he never played in a tournament with grandmaster norms? ”

However, even without the title, Rashid had a prolific chess career, and a lifetime positive score against World Champions – an achievement that is usually exclusive to former world champions. But, perhaps the most humbling explanantion is the one advanced by Rashid himself.

“I came to chess too late, as a 17-year-old man with no theoretical knowledge, whereas all the champions — Botvinnik, Smyslov, Spassky, Petrosian, Tal - received training from the age of seven or eight....Yes, I could play some games with brilliance, and wins prizes for beauty, but I was never able to achieve the holistic skills necessary for Grandmaster level”

What were Rashid’s greatest accomplishments?

If one had to choose, perhaps Rashid’s greatest achievements were, his 5 Russian Chess Championships, and his remarkable performances in any games he contested against World Champions. Given that Rashid rarely ventured out of the USSR, the latter is significantly more interesting.

Notable Negative scores:

Yuri Averbakh 8-0, with 1 draw

Tigran Petrosian 2 – 1, with 2 draws

Viktor Korchnoi 2 – 1, with 3 draws

Notable Positive scores:

Mikhail Tal 3-1 with no draws

Sources

Rashid Nezhmetdinov - Nezhmetdinov's Best Games of Chess (2000, Caissa Editions)

Alex Pishkin – Super Nezh (2000, Thinker’s Press)

If you don’t want to read the books (available on Libgen), you can watch either of the videos below. The narrator is, in large part, reading from the translation of his autobiography.

Jessica Fischer’s three-part documentary on Rashid http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLF4CE9EF136BA63DE&feature=viewall

UniversalChessLyfe’s documentary on Rashid https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0BUZ2zyWRh0

(Both links lead to the same documentary, I’m not sure who deserves credit for it)

Marat Khasanov’s “The Chess History of Tataria” http://www.tat-chess.ru/publ/pochemu_r_nezhmetdinov_ne_stal_grossmejsterom/1-1-0-14

Genna Sosonko’s Smart Chip from St. Petersburg and other tales of a bygone chess era https://archive.org/details/Smart_Chip_from_St.Petersburg

Links for further study

Here are some of my favorite games by Rashid https://www.chessgames.com/perl/chesscollection

More blog posts by nohandlebars

Vishy v. Spassky

The only time Vishwanathan Anand faced Boris Spassky.

Misha v. Vishy

The only game Mikhail Tal played against Vishwanathan Anand.

The Muzio Gambit

The most aggressive variation of one of the most aggressive openings in chess