Age and chess improvement

"The kids are scary man, they are so much smarter and quicker than us, our poor old brains, boohoo..."I am a cognitive neuroscientist who studies human memory and learning. I rant on Twitter every time I hear people complain about their old brains and how that prevents them from making the same sort of progress in chess they see younger adults and kids make. Let us quickly survey how they justify this conclusion:

1. brain plasticity: young brains have more neuroplasticity, hence they progress much more rapidly than older adults

I numbered the list in jest, because what happens most of the time is that people exhaust their ideas right there. The emphasis is just on the brain (and if you change the question to: "Can anyone improve their chess strength to a 2000-2100 FIDE level?", the explanation tends to rest on natural ability and ceilings). You might think that as a neuroscientist, I'd be thrilled that people are interested in my subject enough to attribute most of the difference in chess rating charts to neural causes. However, given that I spent at least 11 years (PhD + postdoctoral training) analyzing behavioral and neural data, never really finding big statistical effects (especially in neural data), I know that is is highly unlikely that a factor that resides in the brain accounts for most of the differences one sees between kids' and adults' rating charts (if such differences indeed are big and real). Before I discuss this in more detail, let me also challenge the basic premise of a big difference in rating charts. Blasphemous! How can this dude deny a basic fact about kids progressing more rapidly?!

I played chess as a kid. Stopped competing at around the age of 12-13. Never really trained, but as many kids do, I played whatever tournaments I could find (which were not many, this was 20-25 years ago in Thrissur, Kerala which btw is where Nihal Sarin is from). I probably got to around 1300-1400 FIDE strength but never got a rating since in those days, you had very different requirements to even get a FIDE rating, and I don't think I even played a FIDE rated tournament. I mostly participated in scholastic events. Fast forward to 2018, I was doing a postdoctoral fellowship in neuroscience at the NIH (Bethesda, MD) when the chess bug bit me again when I participated in a tournament near where I lived and scored 4/7 and won $100 in the U1700 (USCF) section. I then went and played a rapid event and got my ass kicked by 8-10 year olds which is when I decided to start training. You can find more details about my training on the Perpetual Chess Podcast, but what I want to talk about now is this notion that kids improve more rapidly than adults.

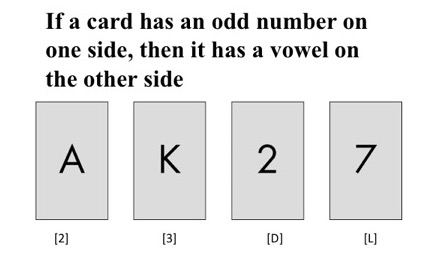

To prepare you to understand the argument though, I need to present to you a simple card "trick". Each of these cards has a number on one side and a letter on the other. There is a hypothesis given in the image below that you have to test by picking two cards to flip to reveal what is on the other side of those cards. The point of the exercise is to determine the most efficient way to do this. Please spend a few minutes thinking about this and choose two cards.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

In this image, I provide one possible configuration of numbers and letters on the other side of each card:

Now let's evaluate your choices:

1. If you picked card A, congrats, you just exhibited a basic human bias called confirmation bias. Let us assume that the A card has the number 2 on the other side. If that is the case, then you have basically no relevant information for your hypothesis which was that if there was an odd number on one side, then you would find a vowel on the other. Since you went hunting to confirm your hypothesis, you decided to pick the card with a vowel hoping to find an odd number on the other side. The critical point here is that even if you did find an odd number on the other side, it takes just one other card that violates this hypothesis to prove you wrong. So if you pursue the card that can prove you right but don't pursue those that can prove you wrong, you will be misled into believing you are correct (because in this game and also in life, you don't have unlimited opportunities to collect data). So picking A is inefficient and wrong, from the perspective of the scientific method.

2. If you picked card with the number 2, it has no information about the hypothesis which only pertains to when there is an odd number on one side. Most people get this right and avoid picking this card.

3. The correct answer therefore is to pick cards K and 7. You would do this easily if you focused on what data would prove your hypothesis wrong instead of hunting for those that would prove you right. So if you flip K and find an odd number on the other side (3 in this example), then that would disprove your hypothesis! So this card is extremely important to pick. If you pick 7 and find a consonant (L) on the other side, that would also be important from a falsification perspective. You may find that they confirm your hypothesis, which would be fine, but the key point here is that if in fact you are wrong, you need to pick the most diagnostic cards that would help you determine that you are indeed wrong. Wason & Johnson-Laird (1972) found that most people tend to pick the cards that would confirm the hypothesis.

How is this exercise and confirmation bias relevant to the current discussion? Well, if you are paying attention only to the rating charts of kids who show amazing rapid progress and pay less attention to the many kids who do not, this is a clear example of confirmation bias. There were several kids who were regulars at the tournaments I played in. Over the 2+ years that I was active, I have tracked many of their rating progress and found that I improved at a similar rate to most of the improving kids. There were several kids who lagged behind me in terms of rating progress. I talked to a few of them, and they had regular GM/IM coaches as well when I had none. However, this is not because I had some sort of chess gene or any special "talent" (another big word that people love to use without having any sort of consensus as to what it exactly means). It was because I was obsessing over chess at this point. I was immersed in it. I was neglecting family and work responsibilities for some part of it. As an adult with responsibilities, there was no way I was sustaining it for a longer period however, but in principle, a kid in middle school or high school should be able to keep up with this sort of immersion and obsession. So if you are only looking at the top 3 kids who did progress at least as rapidly as I did during the period or more, and ignored the several kids who lagged behind, you would conclude that the kids did better. However, for me as a scientist, I require a higher standard of evidence. I need to see truly randomly sampled rating charts. This probably exists out there, so I will assume for now that the difference is real and maybe even a big one.

Btw, in order to counteract these human biases, we as as species have developed a toolbox which is called the scientific method. I will write a separate blog about the key elements of the scientific method and what you should pay attention to when you see big claims about pretty much anything, ranging from chess improvement to COVID-19.

Now back to the question of age and learning, here's James Clear conveying a similar message to what I've been trying to convey to people on the chess Twittersphere (it's more about the time you can spend on it, how much you can immerse yourself in it with no other distractions, etc):

So now, we can finally get back to the question of chess improvement as an adult (note that cognitive decline is real, and there will be limits to how much you can improve if your age hits the range where cognitive decline becomes a real thing but that does not apply to most of the people I see whining over their poor old brains). So what other factors could play a role in explaining the differences between adults and kids?

1. Immersion (ala James Clear's post above about language acquisition)

If you are a 40 year old adult who had to negotiate with your family to play a tournament, and need to use the short break you get in between long classical games to go get something to eat and relax for a bit, then you may also have noticed that kids are accompanied by their parents who do that job for them. What do the kids do in between rounds? That's right, they play chess. They trash talk each other. They discuss chess! They analyze. Then they go home and at least in the US, many of the ones who are serious and can afford a coach, have titled coaches who will analyze their games with them. The 40 year old goes back home and tries to make up for the time spent on the tournament by making up for the chores they missed (or resolving domestic disputes that may arise from it), and gets back to the grind of work and taking care of family responsibilities. And then the 40 year old gets an email with the rating from the tournament and sees some kids who gained 50-60 points, but then looks at his 40 point loss and says "ah well, my poor old dumb brain must be the reason". I'm impressed people actually come to this conclusion.

2. Interference

The concept of interference in memory is a big one that is used by cognitive scientists to explain why people forget information. The idea essentially is as follows: if you eat breakfast in the same room everyday, and have variations of the same breakfast every day, e.g. oats with maybe slightly different mix-ins. I then ask you what you had for breakfast on Wednesday last week. The reason you may get details wrong is because you had many other similar breakfasts on other days and it becomes difficult to distinguish between them. This is an example of interference (or noise) coming from other similar contexts in which you've had breakfast.

Now let us say you have many different smaller items for breakfast everyday. I then ask you whether you had apple for breakfast yesterday. One reason you may not remember clearly simply is because you had 10 different small items everyday, and you cannot remember for sure if apple was one of those items yesterday. This is an example of interference arising from other items you experienced. The more the items you had for breakfast, the more difficult it is to remember if apple was one of them. The contributions of item and context noise or interference have been studied extensively in the laboratory. On a related note, there are even big debates about whether memory consolidation (the phenomenon where with time, a memory becomes progressively resistant to disruption) needs to have an explanation rooted in a very specific brain-based explanations such as synaptic modifications or if you can explain the phenomenon at other levels of analysis. See this article (Gershman et al., 2017) for example.

Why am I saying all this? Well, if you analyze the day-to-day routines of kids vs adults and measure the different types of responsibilities, thoughts, concerns, events etc that the two groups experience, I suspect you would find that adults have a lot more on their plates, which may in fact translate to interference effects in memory. Additionally, if you are reading a chess book on strategy everyday but as soon as you finish reading your book, you have to immediately tend to other duties in the house or at work, your memory system does not get a chance to rehearse what you learned. Rehearsal (of an implicit and silent kind, not as in the Chessable repetitions kind) is another key factor that memory scientists try to measure and factor in when they analyze memory performance. Therefore, all the other stuff that you as an adult needs to tend to may also have interference effects, as in the item noise example in the paragraph above, and/or prevent effective rehearsal.

3. Physical fitness and sleep

When I was training chess seriously, I also had a demanding postdoctoral fellowship job, and an active 5 year old daughter. I can probably count on my fingers the number of nights I got 7+ hours of sleep. I was definitely not finding time for (or prioritizing) exercise. Both of these factors have very important roles in learning and memory and have been studied extensively. Coincidentally, the only tournament I (co-)won came during a period when I was also playing tennis for around 6-7 hrs per week and was also sleeping much better. The two other winners were high schoolers. ;) If you compare the average middle/high schooler and the 40 year old, you should see stark differences in physical fitness levels and also the amounts of sleep the two groups get.

I can probably go on and identify other factors but these are the main ones that come to mind for now. I mainly wrote this so that I can provide a link to this blog to the next person who comes up with the same old tired and lazy argument about weaker/slower older brains as an explanation for the difference between adults' and kids' chess rating charts.

Does this mean anyone can improve as long as they quit their jobs and don't have family responsibilities? No, that is not what this article implies. There are many other factors related to mindset, flexibility, objectivity in evaluating your progress and designing training plans, financial resources, etc that go into the equation. They don't all form a simple linear causal chain to explain chess improvement either. The point of this article is to simply argue against the simplistic view that neuroplasticity and brain-based factors can explain the difference between adults' and kids' ability to learn and improve at chess in any direct and significant way.

References

Wason, P. C., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1972). Psychology of Reasoning: Structure and Content. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gershman, S.J., Monfils, M.-H., Norman, K.A., & Niv, Y. (2017). The computational nature of memory modification. eLife, 6, e23763