Adult Beginner's Guide To... Calculation, Tactics, Puzzles & Pattern Recognition

When I first started studying chess, I was completely overwhelmed. In particular, I struggled to understand all the terminology surrounding one specific part of the game: calculation, tactics, combinations and pattern recognition were all things that were possibly different, but maybe the same? Or some were parts of the other?It confused the shit out of me. I wish someone had sat me down when I first started chess, and told me what each of these things were, why they were important and what I should be doing about each of them. So that is exactly what I aim to do for you in this article: bring clarity to this part of the chess terminology and offer suggestions of ways to train all the chess puzzle-solving abilities you’ll need.

Calculation

As an adult beginner, I had no idea about anything in my first chess games and so there was no logic to any of the moves I played. The first piece or pawn I moved in the opening might just as well have been selected using the 'eenie meenie miney mo' method, because I had no understanding of which method I should apply to make an informed choice. Zero information. If a piece of mine was captured and I had a choice of whether or not to recapture with a piece or a pawn, I just picked... because I had no knowledge to guide whether or why one choice might be better than the other.

And this brings us to skill one when you begin chess - calculation. After my aforementioned piece is captured, choosing whether or not to capture with a pawn or a piece is decided using calculation. It is looking into the future at a branching choice, we can then evaluate the advantages or disadvantages of different moves in a future position that we try to see as clearly (meaning as error free) as possible.

When we first start playing chess (with the most basic knowledge: how the pieces move), our minds intuit that we should move our pieces to try and capture other pieces and not to move them to places where they can be captured. In this way, our beginning thought process is very short term. If I move my queen there and my bishop there I will be threatening checkmate - I hope they don’t notice! If I capture that knight they can recapture with that bishop. When we think of chess like this, we are calculating. We are looking into the future (even if it’s not a very distant one) to determine the consequences of our moves. If you think of you, the chess player, as a video game character then you have only one starting ability - calculation. And you’re shit at it. You’re level one. To level up your calculation ability, you are going to need to do more long-term future-gazing. Initially, this is almost always done by looking at captures. Pieces and pawns capturing other pieces and pawns. This is because if you plan to play a non-capturing move, it is extremely difficult to predict what your opponent might do next - since as a beginner, you have little understanding of why anyone might make any move at all. Thus a large number of responses might seem reasonable to the beginner, but to a more experienced player only two or three might seem likely. Those responses then need to be calculated. In my first games that wasn’t happening. I couldn’t possibly think, if I bring my knight out to f3, they could play... a6, b6, c6, oh wait also a5, b5, c5 oh and Bg4, and Bf5 and so on... If I did, I’d probably still be playing my first game. Thank god for time controls.

So when you first start out, you probably make your first calculations with captures - because you assume that if you capture a piece, your opponent will want to recapture. Re-captures are the one response from your opponent that you feel confident in predicting. So you begin. I take that pawn with my bishop. They take my bishop with their bishop and then my queen captures their bishop. I have captured a pawn and a bishop, they have captured a bishop. Therefore I am winning a pawn. That might be the conclusion of your calculation. Simple. Calculating captures is almost like counting. And calculating itself is the closest thing I can think of to a muscle when it comes to chess. The more you strain your brain trying to see into the future, the stronger the muscle becomes, the further and the clearer you can see, and the better you get at calculating. At least that has been my experience.

If you want to train your calculation skills you need to be mentally moving pieces around in your head. Paradoxically, that does not mean using beginner puzzle books (like the absolutely brilliant Everyone’s First Chess Workbook by Peter Gianatos for example). Great book for many reasons, but in my humble opinion a terrible book if you want to train your calculation skills. Because almost all of the puzzles in that book have one-move answers. Practising calculation by looking only one move ahead into the future is like practising cooking by putting frozen chips in the oven. We are, at the very least, trying to make a bechamel sauce here. You need to look further ahead. As far as you can. So, should you go out and get a book where the answers to the puzzles are on average 8-15 moves deep? Something like Jacob Aagaard’s Grandmaster Preparation: Calculation? No. Do not do that.

At the beginning of my chess journey, I got Common Chess Patterns on Chessable. Another brilliant book and another brilliant mistake. Some of these puzzles I could solve in 5-10 minutes. But I wasn’t calculating when I used that book. I was... searching. I was looking for a move. Any move. Because I just had no clue where to start. I wasn’t calculating. I was lost. That was because I hadn’t learned to recognise any patterns yet. And we will come back to that point.

So what I recommend to practise calculation is simply looking as far as you can along sequences you already know. Calculating a series of captures on a single square is great. Checkmate puzzles could work too, but again I have an issue with this that I’ll get to. King and Pawn endgames are my recommendation. First learn how to win King and 1 Pawn v King (a useful thing to know anyway, even as a total beginner). Then put the pieces in any starting position that seems reasonably close and not obviously winning or losing. And then just start moving the pieces around in your head. My king goes there, their king goes here. My pawn goes here, their king goes there. Do it until your pawn becomes a queen or doesn’t. Then put the kings in a random starting position again and repeat until you forget what day it is. Learning the mechanisms of pawn endgames and doing pawn endgame puzzles has been by far the best way for me to train my raw calculation abilities. I noticed a real and measurable difference in my skills after doing just three puzzles a day for six weeks.

I don’t recommend using general chess puzzle books to train your calculation as an adult beginner. Because the puzzles you can get right (and you want to be getting some right for the sake of your mental health) have too few moves to adequately stretch your calculation muscle, and the puzzles that have a sufficient number of moves to do that are going to leave you totally and utterly lost. You won’t be moving pieces around in your head, you’ll be staring at the page or screen thinking: maybe my knight goes there? Hmm. What if I sacrificed my queen on f7? Naa. I just lose a queen. Maybe g6? It’s frustrating and it’s not worth it.

Tactics

If calculation is the act of sweeping the floor then tactics are the brush. You can’t do tactics anymore than you can do a brush. But people talk about doing tactics all the time. That's because the meaning has gotten lost in the culture. When people say I’m off to do an hour of tactics, they mean I’m off to do an hour of chess puzzles.

So if you can’t do a tactic, then what is it? A tactic can be a pin, a skewer, a double attack, etc. A tactic is more of a spacial construction or typical configuration of pieces than anything else. Now sure you could say: "But you DO a pin" - I’m saying you can’t do a pin. Yes, you can move a piece to pin another piece - but the pin itself only exists as a pin. It is a thing, not a move. These are often called tactical motifs in books. There aren’t really that many of them. If you look at puzzle categories, in ‘tactics trainers’ (which should be called online puzzle libraries) these are often partly sorted by tactical motif. A book like Yasser Sierawan's Winning Chess Tactics can show you what all the tactical motifs are, what they are called and their mechanics.

So we don’t train tactical motifs. You learn tactical motifs. They are simply bits of knowledge to acquire. You either know what a pin is or you don’t.

Puzzles

So we know that when people talk about doing tactics, they actually mean doing chess puzzles. And chess puzzles are where calculation and tactical motifs meet. Unlike in most chess game situations, chess puzzles have one correct answer. There is normally a clear win - either of material (winning a pawn or a piece) or in a checkmate. The tactical motif or checkmate pattern will often be the endpoint of the puzzle, this is the device used to actually win the material. If a single tactical motif is a brick, these bricks are often stacked on top of each other in order to form a puzzle.

For example, you might attack a piece forcing it to move to the only safe square from which it can be forked. This is a combination. A basic puzzle book might require you to only find a fork. A single brick. But a more complex puzzle book will stack these tactical motifs on top of each other.

Pattern Recognition

Whilst tactical motifs are knowledge, pattern recognition is a skill (like calculation). It is part two of getting good at chess puzzles. Remember when I said that Common Chess Patterns didn’t have me calculating for five minutes, but instead it had me staring at a chess puzzle simply searching for five minutes? Well, here is where we find out what I was searching for. Although I didn’t yet know it, my brain was looking for patterns. And I hadn’t seen any. So I would just look and look - and find nothing. Anyone can recognise a pin if shown one. A queen stands in front of her king and in front of that queen stands an enemy rook. The queen is pinned to the king by the rook. A pin. A tactical motif. A thing. However if the puzzle requires me to move my rook to a square where it pins the queen to the king, then when I first see the puzzle, and all the other pieces on the board, I must see that both the king and queen are sitting lined up on the same file - I must see it through all the other ‘noise’ on the chess board. That is a pattern. King and queen lined up. I see it. If I see it enough times, I start noticing a pattern. If I don't see it, then I am going to start looking at random decent looking moves which all lead to nothing. I am going to be staring at the position totally lost.

When a king and queen (or any other piece for that matter) are lined up on the same file, rank or diagonal, then there is the possibility of a pin or skewer in the position. Over time, if I see this configuration of pieces and make the one move that pins/skewers/forks/x-rays that piece configuration enough times, my brain begins to recognise it instantly. And then my brain starts scanning for the piece that can do the pinning/skewing/forking/x-raying. The same goes for checkmate patterns. This is pattern recognition. And the best way to learn to recognise a pattern is to see it again and again and again.

So whereas with calculation the emphasis was on thinking (straining your mental muscles), pattern recognition isn’t actually something you want to feel any effort doing at all. You want it to become subconscious, automatic, instinctive. You want to see a chess board for half a second and hear the voice of your favourite chess podcaster shout "FORK!" inside your mind. It should feel like being immediately slapped in the face by a particularly heavy rainbow trout that has been dipped in garlic sauce. You want to hear it, feel it, see it, smell it. You want to taste it. You want to feel it strike you with the force of a thousand suns.

I train this skill using a salmon, because rainbow trout are rare in my area. You can also use Chessable and a method outlined by Alex Crompton on his blog. I have written a full section on this in a previous post but I have tweaked my training slightly since then so I’ll outline the method below.

I have a number of absolutely basic puzzle books that I have purchased on Chessable. Chessable is a spaced repetition website that will show you the same puzzles over and over again. Each time you get a puzzle right, Chessable won’t show you that puzzle again for a little bit longer each time. Eventually you will only see it once every 6 months as long as you keep getting it right. If you get it wrong you’ll start seeing it everyday again. I set the timer to 30 seconds per puzzle for my first pass through a book and then I reduce the timer to 10 seconds per puzzle. I do exactly 15 minutes per day. I used to do 30 minutes, however due to the way spaced repetition works, it is much more important that you pick a number of minutes per day that you can do every single day than to do more overall time across a week or month. Because if you miss a day, it takes about a week to clear the extra piled up reviews. It’s just the nature of spaced repetition. During that 15 minutes I hit ‘review all’. Once I clear my reviews I start doing new puzzles until my 15 minutes are up. It is much more efficient to do less time everyday than have the possibility of not completing your time, even if you miss one day a month. For a longer explanation of the method, you can also check out Alex Cromton’s interview on The Perpetual Chess Podcast.

There are a number of free basic tactics books on Chessable that are not bad such as ‘Typical Tactical Tricks: 500 Ways to Win!’ and Alan B’s ‘On the Attack’ series. For paid books I recommend Everyone’s First Chess Workbook by Peter Gianatos - it is brilliant, as is Tactics Time 1&2. The Susan Polgar books ‘Learn Chess the Right Way’ are also very good. Whatever you pick, and whether or not you use chessable, or real books ‘Neal Bruce Style’, the point here is volume. Easy 1-2 move tactics, thousands of them, the same puzzles, over and over and over again - until you can solve them in seconds. Until they feel like a saucy fish slap.

And on that bizarre note, I think I will end the first article of my Adult Beginner's Guide To... series. I hope this was helpful and has cleared things up a bit regarding the terminology and how to go about training the two separate skills of calculation and pattern recognition - the two skills needed to solve any chess puzzle. You need to train both to become a better chess player and both should be worked on separately. If you want a nice middle ground, something that has 3-4 move combinations to train both calculation and pattern recognition - then go for it. But my personal view, based on my own experience and research on what's working for other adult beginners, is that these books are simply advanced pattern recognition training tools and that calculation as a skill should be trained separately from pattern recognition, particularly for adult beginners.

Did you know I'm a chess coach now too?

Click here to book a free 60-minute chess lesson with me.

Thanks for reading. This is what I have found works for me, but if you read my blog often, you’ll know that I’m always on the lookout for new, more efficient and better ways to train. I’d love to hear what has worked for others in regards to learning this aspect of chess in the forum for this article so we can all learn from each other.

Please consider supporting the blog as a Patreon Supporter.

To get informed about future articles follow me on Twitter or on Lichess.

See my coaching services.

Freelance enquiries: TheOnoZone@gmail.com

For 20% discount on ChessMood memberships click here.

More blog posts by TheOnoZone

Adult Chess Clock

I used to say that nobody doesn’t have the time for something, they just don’t want to prioritise it.

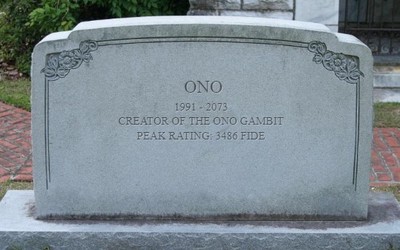

The Ono Gambit

I am getting older.

Losing Consciousness

It was game over.