Teach yourself to be a Resilient Tournament Player

A practical guide to boost your tournament results. Grab a pen and paper.If you’re a dedicated chess player: up and coming, professional, amateur, adult improver, or new to the game ... you work a lot on your game. So much effort goes into all aspects of chess improvements. And yet, when it is time to perform during a chess tournament, a whole array of different skills is required. In this article, I give you a one-stop shop tutorial on the theory and practice of resiliency. If you work on this a little bit, this could give you a lot of tournament points. But nothing is effortless, not your improvement at chess and not your improvements at the mental game: you will need to work at it. This article is meant to be very practical, with exercises and a framework you can apply straight away.

I will ask you to complete exercises as you read along this document so that this won’t be purely a passive learning exercise. The exercises are set in bold italics. Please grab a pen and paper or you open the notes app on your phone.

What is tournament resilience?

To illustrate the importance of resilience, let’s have a look at the following case studies from very recent chess tournament history:

Case study 1:

Candidate tournament, the teenage prodigy plays poorly for the first few games, has a fallout with his coach and then on one night plays hundreds of bullet games until the early hours of the morning (of course, no recovery trajectory).

Case study 2:

World Championship match: The player goes toe to toe with the champion, loses a game and never recovers, complete collapse for the remaining games.

Case study 3:

Super tournament. Teenage Prodigy gets an early huge lead, then a series of draws sees the lead decrease and eventually loses the final game with white to finish second.

Action: Write down your worst tournament collapse. Write a few sentences detailing the circumstances, what triggered the collapse, what happened for the remainder of the tournament

The resilience: ‘bouncebackability’

Some players play much better than others after a loss. Magnus famously has great numbers after a loss (The comeback king by Nate Solon). Magnus is extremely motivated after a defeat. But what is resilience? In the words of Barry Hymer, resilience is not something you are, it is something you do.

It’s not a ‘soft’ quality that you either possess or don’t, but a set of well-defined behaviours. To be resilient is to act optimally under stressors. We will unpack how-to of these behaviours and stressors in a practical framework.

Action: write down “Resilience is a set of behaviours, to act optimally under stressors.”

Stressors

I’ve mentioned stressors but I have not defined them. Obvious stressors are setbacks: losing a game, losing your luggage, playing poorly, but can also be something that is objectively ‘positive’ like winning games and having a big lead in a tournament or home crowd support. Another positive stressor is being paired against a very strong player after good results, being on board 1, or being on a board that is broadcast live if you’re not used to it.

Action: Write down a list of your personal ‘negative’ stressors. Bad things that have an impact on you.

Action: Similarly your personal ‘positive’ stressors, which are objectively ‘positive’ and yet produce stress-inducing thoughts, feelings and emotions

Mindset

To enable change in your resilience, I need to make sure you allow yourself to grow and improve yourself. A growth mindset is the formulation of your shortcomings as “I am not good at this yet”. Typical fixed mindset for chess players:

- “I’m bad at rook endgames”

- “I collapse easily in time trouble”

- “I’m not a good player in very static positions”.

The growth mindset reformulation of these is:

- “I’m practising and improving my rook endgames”

- “I’m improving my time management”

- “I’m working on positional exercises”.

Just like a fixed mindset is very harmful to your chess and your chess development, a fixed mindset toward your mental skills is harmful. I will demand that you approach resilience with a growth mindset. No matter the level of your mental skills right now, recognise that you can improve these skill

Action: Find an example of a limiting belief of a fixed mindset that you have for your chess, and then rephrase it with a growth mindset.

Getting upset at tournaments and bothered is normal and unavoidable. It is part and parcel of being a human being. Nevertheless:

- You can get better at cultivating equanimity

- You can get better at recognising your own mental and physical state

- You can get better at devising and implementing strategies to deal with the stressors.

You likely work a lot on your chess. You should work on your mental game as well. It is not easy but neither is chess, and these skills will pay dividends at tournaments and last a lifetime.

Action: Write “I know that I can improve my mental game and I commit to work on it.”

As a chess improver, you are likely very aware of the difference between skills and knowledge: It is very easy to accrue chess knowledge without seeing an improvement in playing strength because what matters is the skilful application of the knowledge. The mental game is similar: we need knowledge of a theoretical framework, and skills to practice.

The Theoretical Framework

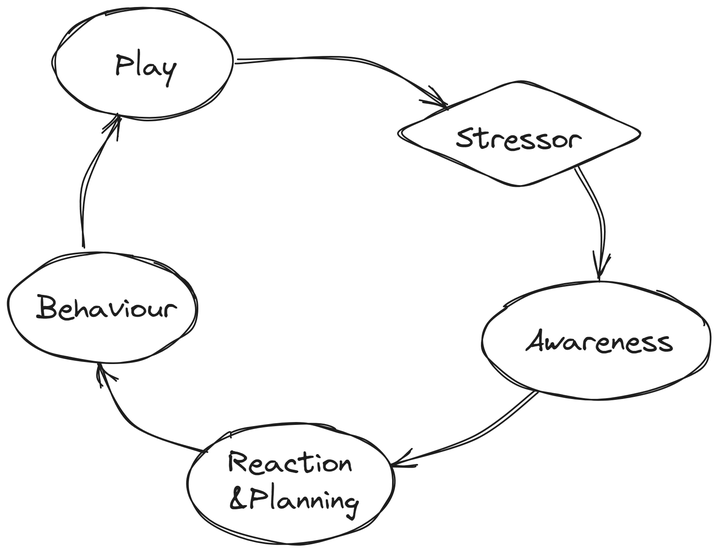

Armed with the mindset of improving our resilience, let’s lay down the key points:

- You play chess! This is fun but ...

- Stressors will appear

- You become aware of the stressors

- React appropriately to the stressors and plan for appropriate behaviour

- Act out the planned behaviour

- Play more!

This is shown in the following figure

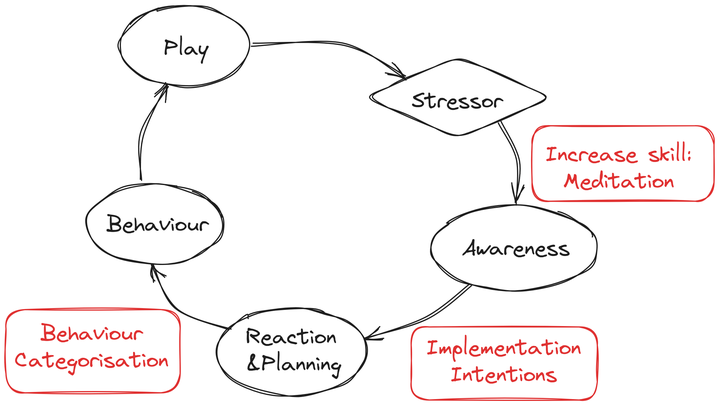

The practical framework.

Having a theoretical framework above is very valuable, but how to carry it out in practice? We need to be skilled at getting awareness of the stressors and at categorising and planning our behaviours.

Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness will be our way to be skilful at recognizing our internal state. By developing a meditation practice, you progressively gain the mental space to watch your mental state and be able to recognise it as an appearance in awareness. Two of the main types of meditation are

- focus, where we shine the flashlight of attention on a single phenomenon, typically the breath

- Insight, where we rest as the background of awareness and observe the thoughts, feelings and emotions come and go.

I think a mix of both is really valuable. I have created my own Chess Mindfulness video course, so of course I would recommend it, but there exists a large amount of free quality material online.

It is particularly important for the players to have a practice before the games and to also have a high awareness of their mental states after the games. You’re by far the best placed to notice subtle changes in your thought patterns and emotions.

Act like a high-performance player: Behaviour categorisation

I invite you to categorise your behaviours into high-performance and low-performance. It is imperative to do this ahead of time.

Examples of low-performance behaviour

- Reminiscing about missed opportunities.

- Giving up easily (not trying to swindle).

- Thinking catastrophically

- Sleeping late, eating junk food, drinking alcohol

- Playing bullet until 4 am

Example of high-performance behaviour

- Playing the current position

- Fighting for every point and every half-point

- Creating problems for your opponent

- Not being impressed by the rating of opponent

- Assessing the tournament situation objectively

- Proper framing of chess in life

- Sleeping on time, eating properly, exercising regularly

Action: Write down your own high and low-performance behaviours

Implementation Intentions

Now this is where the rubber meets the road. Implementation Intentions are if ... then ... statements that you fill in ahead of time so that you know how to react when the appropriate situation occurs.

IF {situation} THEN I will {behaviour}

{situation}: list your top stressors

{behaviours}: use high-performance behaviours (for example)

IF {I lose a game} THEN I will *{go for a walk and refocus for the next game, and have the same regular prep}*IF {my laptop breaks} THEN I will {use my phone to prepare and ask for help}

IF {I am paired on board one after a good run} THEN I WILL {play it like any other game and treat the pressure as a privilege}

Action: Write down your own if ... then ... implementation intentions, using the list of stressors you already wrote down, and the list of high performance behaviours.

Putting everything together

Armed with an understanding of the arising of stressors and the realisation that we need to change our behaviour when they arise. The skills associated with making this run smoothly are developed by

- Setting up a regular meditation practice to gain better awareness of your emotions, and cultivate equanimity.

- Listing your stressors and your low- and high-performance behaviours

- Setting up your own ‘implementation intentions’ for getting back on track and having a high-performance behaviour. Stressors do happen, it’s up to you to respond and not react.

I know doing a ‘one size fits all’ setup for resilience is a quixotic endeavour but I do hope you try this framework and don’t hesitate to comment for any questions.

More blog posts by BenjiPortheault

Tournament Formats in Professional Chess

Getting the conversation started on the drawbacks of ubiquitous formats

The xG of Chess: Shark Points

A metric to quantify missed chances

Leaning into discomfort

Stop trying to trick yourself into focusing on what is important and address the root cause of distr…