Chess

WHAT IS THE CHESSChess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to distinguish it from related games, such as xiangqi (Chinese chess) and shogi (Japanese chess). The recorded history of chess goes back at least to the emergence of a similar game, chaturanga, in seventh-century India. The rules of chess as we know them today emerged in Europe at the end of the 15th century, with standardization and universal acceptance by the end of the 19th century. Today, chess is one of the world's most popular games, played by millions of people worldwide.

Chess is an abstract strategy game that involves no hidden information and no use of dice or cards. It is played on a chessboard with 64 squares arranged in an eight-by-eight grid. At the start, each player controls sixteen pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights, and eight pawns. White moves first, followed by Black. Checkmating the opponent's king involves putting the king under immediate attack (in "check") whereby there is no way for it to escape. There are also several ways a game can end in a draw.

Organized chess arose in the 19th century. Chess competition today is governed internationally by FIDE (the International Chess Federation). The first universally recognized World Chess Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, claimed his title in 1886; Magnus Carlsen is the current World Champion. A huge body of chess theory has developed since the game's inception. Aspects of art are found in chess composition, and chess in its turn influenced Western culture and art, and has connections with other fields such as mathematics, computer science, and psychology.

One of the goals of early computer scientists was to create a chess-playing machine. In 1997, Deep Blue became the first computer to beat the reigning World Champion in a match when it defeated Garry Kasparov. Today's chess engines are significantly stronger than the best human players and have deeply influenced the development of chess theory.

This article uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves.

Time control

A digital chess clock

In competition, chess games are played with a time control. If a player's time runs out before the game is completed, the game is automatically lost (provided the opponent has enough pieces left to deliver checkmate).[1] The duration of a game ranges from long (or "classical") games, which can take up to seven hours (even longer if adjournments are permitted), to bullet chess (under 3 minutes per player for the entire game). Intermediate between these are rapid chess games, lasting between one and two hours per game, a popular time control in amateur weekend tournaments.

Time is controlled using a chess clock that has two displays, one for each player's remaining time. Analog chess clocks have been largely replaced by digital clocks, which allow for time controls with increments.

Time controls are also enforced in correspondence chess competitions. A typical time control is 50 days for every 10 moves.

Tournaments and matches

Tata Steel Chess Tournament 2019, Wijk aan Zee (the Netherlands)

Contemporary chess is an organized sport with structured international and national leagues, tournaments, and congresses. Thousands of chess tournaments, matches, and festivals are held around the world every year catering to players of all levels.

Tournaments with a small number of players may use the round-robin format, in which every player plays one game against every other player. For a large numbers of players, the Swiss system may be used, in which each player is paired against an opponent who has the same (or as similar as possible) score in each round. In either case, a player's score is usually calculated as 1 point for each game won and one-half point for each game drawn. Variations such as "football scoring" (3 points for a win, 1 point for a draw) may be used by tournament organizers, but ratings are always calculated on the basis of standard scoring. There are different ways to denote a player's score in a match or tournament, most commonly: P/G (points scored out of games played, e.g. 5½/8); P–A (points for and points against, e.g. 5½–2½); or +W−L=D (W wins, L losses, D draws, e.g. +4−1=3).

The term "match" refers not to an individual game, but to either a series of games between two players, or a team competition in which each player of one team plays one game against a player of the other team.

Governance

Chess's international governing body is usually known by its French acronym FIDE (pronounced FEE-day) (French: Fédération internationale des échecs), or International Chess Federation. FIDE's membership consists of the national chess organizations of over 180 countries; there are also several associate members, including various supra-national organizations, the International Braille Chess Association (IBCA), International Committee of Chess for the Deaf (ICCD), and the International Physically Disabled Chess Association (IPCA).[9] FIDE is recognized as a sports governing body by the International Olympic Committee,[10] but chess has never been part of the Olympic Games.

Garry Kasparov, former World Chess Champion

FIDE's most visible activity is organizing the World Chess Championship, a role it assumed in 1948. The current World Champion is Magnus Carlsen of Norway.[11] The reigning Women's World Champion is Ju Wenjun from China.[12]

Other competitions for individuals include the World Junior Chess Championship, the European Individual Chess Championship, the tournaments for the World Championship qualification cycle, and the various national championships. Invitation-only tournaments regularly attract the world's strongest players. Examples include Spain's Linares event, Monte Carlo's Melody Amber tournament, the Dortmund Sparkassen meeting, Sofia's M-tel Masters, and Wijk aan Zee's Tata Steel tournament.

Regular team chess events include the Chess Olympiad and the European Team Chess Championship.

The World Chess Solving Championship and World Correspondence Chess Championships include both team and individual events; these are held independently of FIDE.

Titles and rankings

Main article: Chess titles

In order to rank players, FIDE, ICCF, and most national chess organizations use the Elo rating system developed by Arpad Elo. An average club player has a rating of about 1500; the highest FIDE rating of all time, 2882, was achieved by Magnus Carlsen on the March 2014 FIDE rating list.[13]

Players may be awarded lifetime titles by FIDE:[15]

- Grandmaster (GM; sometimes International Grandmaster or IGM is used) is awarded to world-class chess masters. Apart from World Champion, Grandmaster is the highest title a chess player can attain. Before FIDE will confer the title on a player, the player must have an Elo rating of at least 2500 at one time and three results of a prescribed standard (called norms) in tournaments involving other grandmasters, including some from countries other than the applicant's. There are other milestones a player can achieve to attain the title, such as winning the World Junior Championship.

- International Master (IM). The conditions are similar to GM, but less demanding. The minimum rating for the IM title is 2400.

- FIDE Master (FM). The usual way for a player to qualify for the FIDE Master title is by achieving a FIDE rating of 2300 or more.

- Candidate Master (CM). Similar to FM, but with a FIDE rating of at least 2200.

The above titles are open to both men and women. There are also separate women-only titles; Woman Grandmaster (WGM), Woman International Master (WIM), Woman FIDE Master (WFM) and Woman Candidate Master (WCM). These require a performance level approximately 200 Elo rating points below the similarly named open titles, and their continued existence has sometimes been controversial. Beginning with Nona Gaprindashvili in 1978, a number of women have earned the open GM title.[note 2]

FIDE also awards titles for arbiters and trainers.[16][17] International titles are also awarded to composers and solvers of chess problems and to correspondence chess players (by the International Correspondence Chess Federation). National chess organizations may also award titles.

Theory

Main articles: Chess theory, Chess tactics, Chess strategy, Chess libraries, List of chess books, and List of chess periodicals

Chess has an extensive literature. In 1913, the chess historian H.J.R. Murray estimated the total number of books, magazines, and chess columns in newspapers to be about 5,000.[18] B.H. Wood estimated the number, as of 1949, to be about 20,000.[19] David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld write that, "Since then there has been a steady increase year by year of the number of new chess publications. No one knows how many have been printed."[19] Significant public chess libraries include the John G. White Chess and Checkers Collection at Cleveland Public Library, with over 32,000 chess books and over 6,000 bound volumes of chess periodicals;[20] and the Chess & Draughts collection at the National Library of the Netherlands, with about 30,000 books.[21]

Chess theory usually divides the game of chess into three phases with different sets of strategies: the opening, typically the first 10 to 20 moves, when players move their pieces to useful positions for the coming battle; the middlegame; and last the endgame, when most of the pieces are gone, kings typically take a more active part in the struggle, and pawn promotion is often decisive.

Opening theory is concerned with finding the best moves in the initial phase of the game. There are dozens of different openings, and hundreds of variants. The Oxford Companion to Chess lists 1,327 named openings and variants.[22]

Middlegame theory is usually divided into chess tactics and chess strategy. Chess strategy concentrates on setting and achieving long-term positioning advantages during the game – for example, where to place different pieces – while tactics concerns immediate maneuver. These two aspects of the gameplay cannot be completely separated, because strategic goals are mostly achieved through tactics, while the tactical opportunities are based on the previous strategy of play.

Endgame theory is concerned with positions where there are only a few pieces left. Theoretics categorize these positions according to the pieces, for example "King and pawn endings" or "Rook versus a minor piece".

Opening

Main article: Chess opening

A chess opening is the group of initial moves of a game (the "opening moves"). Recognized sequences of opening moves are referred to as openings and have been given names such as the Ruy Lopez or Sicilian Defense. They are catalogued in reference works such as the Encyclopaedia of Chess Openings. There are dozens of different openings, varying widely in character from quiet positional play (for example, the Réti Opening) to very aggressive (the Latvian Gambit). In some opening lines, the exact sequence considered best for both sides has been worked out to more than 30 moves.[23] Professional players spend years studying openings and continue doing so throughout their careers, as opening theory continues to evolve.

The fundamental strategic aims of most openings are similar:[24]

- development: This is the technique of placing the pieces (particularly bishops and knights) on useful squares where they will have an optimal impact on the game.

- control of the center: Control of the central squares allows pieces to be moved to any part of the board relatively easily, and can also have a cramping effect on the opponent.

- king safety: It is critical to keep the king safe from dangerous possibilities. A correctly timed castling can often enhance this.

- pawn structure: Players strive to avoid the creation of pawn weaknesses such as isolated, doubled, or backward pawns, and pawn islands – and to force such weaknesses in the opponent's position.

Most players and theoreticians consider that White, by virtue of the first move, begins the game with a small advantage. This initially gives White the initiative.[25] Black usually strives to neutralize White's advantage and achieve equality, or to develop dynamic counterplay in an unbalanced position.

Middlegame

Main article: Chess middlegame

The middlegame is the part of the game which starts after the opening. There is no clear line between the opening and the middlegame, but typically the middlegame will start when most pieces have been developed. (Similarly, there is no clear transition from the middlegame to the endgame; see start of the endgame.) Because the opening theory has ended, players have to form plans based on the features of the position, and at the same time take into account the tactical possibilities of the position.[26] The middlegame is the phase in which most combinations occur. Combinations are a series of tactical moves executed to achieve some gain. Middlegame combinations are often connected with an attack against the opponent's king. Some typical patterns have their own names; for example, the Boden's Mate or the Lasker–Bauer combination.[27]

Specific plans or strategic themes will often arise from particular groups of openings which result in a specific type of pawn structure. An example is the minority attack, which is the attack of queenside pawns against an opponent who has more pawns on the queenside. The study of openings is therefore connected to the preparation of plans that are typical of the resulting middlegames.[28]

Another important strategic question in the middlegame is whether and how to reduce material and transition into an endgame (i.e. simplify). Minor material advantages can generally be transformed into victory only in an endgame, and therefore the stronger side must choose an appropriate way to achieve an ending. Not every reduction of material is good for this purpose; for example, if one side keeps a light-squared bishop and the opponent has a dark-squared one, the transformation into a bishops and pawns ending is usually advantageous for the weaker side only, because an endgame with bishops on opposite colors is likely to be a draw, even with an advantage of a pawn, or sometimes even with a two-pawn advantage.[29]

Tactics

Main article: Chess tactics

In chess, tactics in general concentrate on short-term actions – so short-term that they can be calculated in advance by a human player or a computer. The possible depth of calculation depends on the player's ability. In quiet positions with many possibilities on both sides, a deep calculation is more difficult and may not be practical, while in positions with a limited number of forced variations, strong players can calculate long sequences of moves.

Theoreticians describe many elementary tactical methods and typical maneuvers, for example: pins, forks, skewers, batteries, discovered attacks (especially discovered checks), zwischenzugs, deflections, decoys, sacrifices, underminings, overloadings, and interferences.[30] Simple one-move or two-move tactical actions – threats, exchanges of material, and double attacks – can be combined into more complicated sequences of tactical maneuvers that are often forced from the point of view of one or both players.[31] A forced variation that involves a sacrifice and usually results in a tangible gain is called a combination.[31] Brilliant combinations – such as those in the Immortal Game – are considered beautiful and are admired by chess lovers. A common type of chess exercise, aimed at developing players' skills, is a position where a decisive combination is available and the challenge is to find it.[32]

Strategy

Main article: Chess strategy

| Example of underlying pawn structure |

|---|

abcdefgh8                             877665544332211abcdefghPosition after 12...Re8 ...Tarrasch vs. Euwe, Bad Pistyan (1922)[33] 877665544332211abcdefghPosition after 12...Re8 ...Tarrasch vs. Euwe, Bad Pistyan (1922)[33] |

Chess strategy is concerned with the evaluation of chess positions and with setting up goals and long-term plans for future play. During the evaluation, players must take into account numerous factors such as the value of the pieces on the board, control of the center and centralization, the pawn structure, king safety, and the control of key squares or groups of squares (for example, diagonals, open files, and dark or light squares).

The most basic step in evaluating a position is to count the total value of pieces of both sides.[34] The point values used for this purpose are based on experience; usually, pawns are considered worth one point, knights and bishops about three points each, rooks about five points (the value difference between a rook and a bishop or knight being known as the exchange), and queens about nine points. The king is more valuable than all of the other pieces combined, since its checkmate loses the game. But in practical terms, in the endgame, the king as a fighting piece is generally more powerful than a bishop or knight but less powerful than a rook.[35] These basic values are then modified by other factors like position of the piece (e.g. advanced pawns are usually more valuable than those on their initial squares), coordination between pieces (e.g. a pair of bishops usually coordinate better than a bishop and a knight), or the type of position (e.g. knights are generally better in closed positions with many pawns while bishops are more powerful in open positions).[36]

Another important factor in the evaluation of chess positions is pawn structure (sometimes known as the pawn skeleton): the configuration of pawns on the chessboard.[37] Since pawns are the least mobile of the pieces, pawn structure is relatively static and largely determines the strategic nature of the position. Weaknesses in pawn structure include isolated, doubled, or backward pawns and holes; once created, they are often permanent. Care must therefore be taken to avoid these weaknesses unless they are compensated by another valuable asset (for example, by the possibility of developing an attack).[38]

History

Main article: History of chess

Origins

Sasanian Empire King Khosrow I sits on his throne before the chessboard, while his vizir and the Indian envoy, probably sent by the Maukhari King Śarvavarman of Kannauj, are playing chess. Shahnama, 10th century AD.[40][41]

The earliest texts referring to the origins of chess date from the beginning of the 7th century. Three are written in Pahlavi (Middle Persian)[42] and one, the Harshacharita, is in Sanskrit.[43] One of these texts, the Chatrang-namak, represents one of the earliest written accounts of chess. The narrator Bozorgmehr explains that Chatrang, the Pahlavi word for chess, was introduced to Persia by 'Dewasarm, a great ruler of India' during the reign of Khosrow I.[44]

The oldest known chess manual was in Arabic and dates to about 840, written by al-Adli ar-Rumi (800–870), a renowned Arab chess player, titled Kitab ash-shatranj (The Book of Chess). This is a lost manuscript, but is referenced in later works.[45] Here also, al-Adli attributes the origins of Persian chess to India, along with the eighth-century collection of fables Kalīla wa-Dimna.[46] By the twentieth century, a substantial consensus[47][48] developed regarding chess's origins in northwest India in the early 7th century.[49][50] More recently, this consensus has been the subject of further scrutiny.[51]

The early forms of chess in India were known as chaturaṅga (Sanskrit: चतुरङ्ग), literally "four divisions" [of the military] – infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariotry – represented by pieces which would later evolve into the modern pawn, knight, bishop, and rook, respectively. Chaturanga was played on an 8×8 uncheckered board, called ashtāpada.[52] Thence it spread eastward and westward along the Silk Road. The earliest evidence of chess is found in the nearby Sasanian Persia around 600 A.D., where the game came to be known by the name chatrang (Persian: چترنگ).[53] Chatrang was taken up by the Muslim world after the Islamic conquest of Persia (633–51), where it was then named shatranj (Arabic: شطرنج; Persian: شترنج), with the pieces largely retaining their Persian names. In Spanish, "shatranj" was rendered as ajedrez ("al-shatranj"), in Portuguese as xadrez, and in Greek as ζατρίκιον (zatrikion, which comes directly from the Persian chatrang),[54] but in the rest of Europe it was replaced by versions of the Persian shāh ("king"), from which the English words "check" and "chess" descend.[note 3] The word "checkmate" is derived from the Persian shāh māt ("the king is dead").[55]

Knights Templar playing chess, Libro de los juegos, 1283

Xiangqi is the form of chess best-known in China. The eastern migration of chess, into China and Southeast Asia, has even less documentation than its migration west, making it largely conjectured. The word xiàngqí 象棋 was used in China to refer to a game from 569 A.D. at the latest, but it has not been proven if this game was or was not directly related to chess.[56][57] The first reference to Chinese chess appears in a book entitled Xuán guaì lù 玄怪錄 ("Record of the Mysterious and Strange"), dating to about 800. A minority view holds that western chess arose from xiàngqí or one of its predecessors,[58] although this has been contested.[59] Chess historians Jean-Louis Cazaux and Rick Knowlton contend that xiangqi's intrinsic characteristics make it easier to construct an evolutionary path from China to India/Persia than the opposite direction.[60]

The oldest archaeological chess artifacts – ivory pieces – were excavated in ancient Afrasiab, today's Samarkand, in Uzbekistan, Central Asia, and date to about 760, with some of them possibly being older. Remarkably, almost all findings of the oldest pieces come from along the Silk Road, from the former regions of the Tarim Basin (today's Xinjiang in China), Transoxiana, Sogdiana, Bactria, Gandhara, to Iran on one end and to India through Kashmir on the other.[61]

The game reached Western Europe and Russia via at least three routes, the earliest being in the 9th century. By the year 1000, it had spread throughout both the Muslim Iberia and Latin Europe.[62] A Latin poem called Versus de scachis ("Verses on Chess") dated to the late 10th century, has been preserved at Einsiedeln Abbey in Switzerland.

1200–1700: Origins of the modern game

The game of chess was then played and known in all European countries. A famous 13th-century Spanish manuscript covering chess, backgammon, and dice is known as the Libro de los juegos, which is the earliest European treatise on chess as well as being the oldest document on European tables games. The rules were fundamentally similar to those of the Arabic shatranj. The differences were mostly in the use of a checkered board instead of a plain monochrome board used by Arabs and the habit of allowing some or all pawns to make an initial double step. In some regions, the Queen, which had replaced the Wazir, and/or the King could also make an initial two-square leap under some conditions.[63]

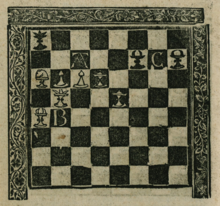

A tactical puzzle from Lucena's 1497 book

Around 1200, the rules of shatranj started to be modified in Europe, culminating, several major changes later, in the emergence of modern chess practically as it is known today.[64] A major change was the modern piece movement rules, which began to appear in intellectual circles in Valencia, Spain, around 1475,[note 4] which established the foundations and brought it very close to current Chess. These new rules then were quickly adopted in Italy and Southern France before diffusing into the rest of Europe.[67][68] Pawns gained the ability to advance two squares on their first move, while bishops and queens acquired their modern movement powers. The queen replaced the earlier vizier chess piece toward the end of the 10th century and by the 15th century had become the most powerful piece;[69] in light of that, modern chess was often referred to at the time as "Queen's Chess" or "Mad Queen Chess".[70] Castling, derived from the "king's leap", usually in combination with a pawn or rook move to bring the king to safety, was introduced. These new rules quickly spread throughout Western Europe.

Writings about chess theory began to appear in the late 15th century. An anonymous treatise on chess of 1490 with the first part containing some openings and the second 30 endgames is deposited in the library of the University of Göttingen.[71] The book El Libro dels jochs partitis dels schachs en nombre de 100 was written by Francesc Vicent in Segorbe in 1495, but no copy of this work has survived.[71] The Repetición de Amores y Arte de Ajedrez (Repetition of Love and the Art of Playing Chess) by Spanish churchman Luis Ramírez de Lucena was published in Salamanca in 1497.[68] Lucena and later masters like Portuguese Pedro Damiano, Italians Giovanni Leonardo Di Bona, Giulio Cesare Polerio and Gioachino Greco, and Spanish bishop Ruy López de Segura developed elements of opening theory and started to analyze simple endgames.

1700–1873: Romantic era

The "Immortal Game", Anderssen vs. Kieseritzky, 1851

In the 18th century, the center of European chess life moved from Southern Europe to mainland France. The two most important French masters were François-André Danican Philidor, a musician by profession, who discovered the importance of pawns for chess strategy, and later Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais, who won a famous series of matches against Irish master Alexander McDonnell in 1834.[72] Centers of chess activity in this period were coffee houses in major European cities like Café de la Régence in Paris and Simpson's Divan in London.[73][74]

At the same time, the intellectual movement of romanticism had had a far-reaching impact on chess, with aesthetics and tactical beauty being held in higher regard than objective soundness and strategic planning. As a result, virtually all games began with the Open Game, and it was considered unsportsmanlike to decline gambits that invited tactical play such as the King's Gambit and the Evans Gambit.[75] This chess philosophy is known as Romantic chess, and a sharp, tactical style consistent with the principles of chess romanticism was predominant until the late 19th century.[76]

The rules concerning stalemate were finalized in the early 19th century. Also in the 19th century, the convention that White moves first was established (formerly either White or Black could move first). Finally, the rules around castling and en passant captures were standardized – variations in these rules persisted in Italy until the late 19th century. The resulting standard game is sometimes referred to as Western chess[77] or international chess,[78] particularly in Asia where other games of the chess family such as xiangqi are prevalent. Since the 19th century, the only rule changes, such as the establishment of the correct procedure for claiming a draw by repetition, have been technical in nature.

Chess in the Netherlands (1864)

As the 19th century progressed, chess organization developed quickly. Many chess clubs, chess books, and chess journals appeared. There were correspondence matches between cities; for example, the London Chess Club played against the Edinburgh Chess Club in 1824.[79] Chess problems became a regular part of 19th-century newspapers; Bernhard Horwitz, Josef Kling, and Samuel Loyd composed some of the most influential problems. In 1843, von der Lasa published his and Bilguer's Handbuch des Schachspiels (Handbook of Chess), the first comprehensive manual of chess theory.

The first modern chess tournament was organized by Howard Staunton, a leading English chess player, and was held in London in 1851. It was won by the German Adolf Anderssen, who was hailed as the leading chess master. His brilliant, energetic attacking style was typical for the time.[80][81] Sparkling games like Anderssen's Immortal Game and Evergreen Game or Morphy's "Opera Game" were regarded as the highest possible summit of the art of chess.[82]

Deeper insight into the nature of chess came with the American Paul Morphy, an extraordinary chess prodigy. Morphy won against all important competitors (except Staunton, who refused to play), including Anderssen, during his short chess career between 1857 and 1863. Morphy's success stemmed from a combination of brilliant attacks and sound strategy; he intuitively knew how to prepare attacks.[83]

1873–1945: Birth of a sport

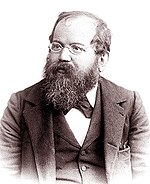

Wilhelm Steinitz, the first official World Chess Champion, from 1886 to 1894

Prague-born Wilhelm Steinitz laid the foundations for a scientific approach to the game, the art of breaking a position down into components[84] and preparing correct plans.[85] In addition to his theoretical achievements, Steinitz founded an important tradition: his triumph over the leading German master Johannes Zukertort in 1886 is regarded as the first official World Chess Championship. This win marked a stylistic transition at the highest levels of chess from an attacking, tactical style predominant in the Romantic era to a more positional, strategic style introduced to the chess world by Steinitz. Steinitz lost his crown in 1894 to a much younger player, the German mathematician Emanuel Lasker, who maintained this title for 27 years, the longest tenure of any world champion.[86]

After the end of the 19th century, the number of master tournaments and matches held annually quickly grew. The first Olympiad was held in Paris in 1924, and FIDE was founded initially for the purpose of organizing that event. In 1927, the Women's World Chess Championship was established; the first to hold the title was Czech-English master Vera Menchik.[87]

A prodigy from Cuba, José Raúl Capablanca, known for his skill in endgames, won the World Championship from Lasker in 1921. Capablanca was undefeated in tournament play for eight years, from 1916 to 1924. His successor (1927) was the Russian-French Alexander Alekhine, a strong attacking player who died as the world champion in 1946. Alekhine briefly lost the title to Dutch player Max Euwe in 1935 and regained it two years later.[88]

In the interwar period, chess was revolutionized by the new theoretical school of so-called hypermodernists like Aron Nimzowitsch and Richard Réti. They advocated controlling the center of the board with distant pieces rather than with pawns, thus inviting opponents to occupy the center with pawns, which become objects of attack.[89]

1945–1990: Post-World War II era

Bobby Fischer, World Champion from 1972 to 1975

After the death of Alekhine, a new World Champion was sought. FIDE, which has controlled the title since then, ran a tournament of elite players. The winner of the 1948 tournament was Russian Mikhail Botvinnik. In 1950 FIDE established a system of titles, conferring the titles of Grandmaster and International Master on 27 players. (Some sources state that in 1914 the title of chess Grandmaster was first formally conferred by Tsar Nicholas II of Russia to Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch, and Marshall, but this is a disputed claim.[note 5])

Mikhail Botvinnik, the first post-war World Champion

Botvinnik started an era of Soviet dominance in the chess world, which mainly through the Soviet government's politically inspired efforts to demonstrate intellectual superiority over the West[90][91] stood almost uninterrupted for more than a half-century. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there was only one non-Soviet champion, American Bobby Fischer (champion 1972–1975).[92] Botvinnik also revolutionized opening theory. Previously, Black strove for equality, attempting to neutralize White's first-move advantage. As Black, Botvinnik strove for the initiative from the beginning.[93] In the previous informal system of World Championships, the current champion decided which challenger he would play for the title and the challenger was forced to seek sponsors for the match. FIDE set up a new system of qualifying tournaments and matches. The world's strongest players were seeded into Interzonal tournaments, where they were joined by players who had qualified from Zonal tournaments. The leading finishers in these Interzonals would go through the "Candidates" stage, which was initially a tournament, and later a series of knockout matches. The winner of the Candidates would then play the reigning champion for the title. A champion defeated in a match had a right to play a rematch a year later. This system operated on a three-year cycle. Botvinnik participated in championship matches over a period of fifteen years. He won the world championship tournament in 1948 and retained the title in tied matches in 1951 and 1954. In 1957, he lost to Vasily Smyslov, but regained the title in a rematch in 1958. In 1960, he lost the title to the 23-year-old Latvian prodigy Mikhail Tal, an accomplished tactician and attacking player who is widely regarded as one of the most creative players ever,[94] hence his nickname "the magician from Riga". Botvinnik again regained the title in a rematch in 1961.

Following the 1961 event, FIDE abolished the automatic right of a deposed champion to a rematch, and the next champion, Armenian Tigran Petrosian, a player renowned for his defensive and positional skills, held the title for two cycles, 1963–1969. His successor, Boris Spassky from Russia (champion 1969–1972), won games in both positional and sharp tactical style.[95] The next championship, the so-called Match of the Century, saw the first non-Soviet challenger since World War II, American Bobby Fischer. Fischer defeated his opponents in the Candidates matches by unheard-of margins, and convincingly defeated Spassky for the world championship. The match was followed closely by news media of the day, leading to a surge in popularity for chess; it also held significant political importance at the height of the Cold War, with the match being seen by both sides as a microcosm of the conflict between East and West.[96] In 1975, however, Fischer refused to defend his title against Soviet Anatoly Karpov when he was unable to reach agreement on conditions with FIDE, and Karpov obtained the title by default.[97] Fischer modernized many aspects of chess, especially by extensively preparing openings.[98]

Karpov defended his title twice against Viktor Korchnoi and dominated the 1970s and early 1980s with a string of tournament successes.[99] In the 1984 World Chess Championship, Karpov faced his toughest challenge to date, the young Garry Kasparov from Baku, Soviet Azerbaijan. The match was aborted in controversial circumstances after 5 months and 48 games with Karpov leading by 5 wins to 3, but evidently exhausted; many commentators believed Kasparov, who had won the last two games, would have won the match had it continued. Kasparov won the 1985 rematch. Kasparov and Karpov contested three further closely fought matches in 1986, 1987 and 1990, Kasparov winning them all.[100] Kasparov became the dominant figure of world chess from the mid 1980s until his retirement from competition in 2005.

Beginnings of chess technology

Chess-playing computer programs (later known as chess engines) began to appear in the 1960s. In 1970, the first major computer chess tournament, the North American Computer Chess Championship, was held, followed in 1974 by the first World Computer Chess Championship. In the late 1970s, dedicated home chess computers such as Fidelity Electronics' Chess Challenger became commercially available, as well as software to run on home computers. However, the overall standard of computer chess was low until the 1990s.

The first endgame tablebases, which provided perfect play for relatively simple endgames such as king and rook versus king and bishop, appeared in the late 1970s. This set a precedent to the complete six- and seven-piece tablebases that became available in the 2000s and 2010s respectively.[101]

The first commercial chess database, a collection of chess games searchable by move and position, was introduced by the German company ChessBase in 1987. Databases containing millions of chess games have since had a profound effect on opening theory and other areas of chess research.

Digital chess clocks were invented in 1973, though they did not become commonplace until the 1990s. Digital clocks allow for time controls involving increments and delays.

1990–present: Rise of computers and online chess

Technology

The Internet enabled online chess as a new medium of playing, with chess servers allowing users to play other people from different parts of the world in real time. The first such server, known as Internet Chess Server or ICS, was developed at the University of Utah in 1992. ICS formed the basis for the first commercial chess server, the Internet Chess Club, which was launched in 1995, and for other early chess servers such as FICS (Free Internet Chess Server). Since then, many other platforms have appeared, and online chess began to rival over-the-board chess in popularity.[102][103] During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the isolation ensuing from quarantines imposed in many places around the world, combined with the success of the popular Netflix show The Queen's Gambit and other factors such as the popularity of online tournaments (notably PogChamps) and chess Twitch streamers, resulted in a surge of popularity not only for online chess, but for the game of chess in general; this phenomenon has been referred to in the media as the 2020 online chess boom.[104][105]

Computer chess has also seen major advances. By the 1990s, chess engines could consistently defeat most amateurs, and in 1997 Deep Blue defeated World Champion Garry Kasparov in a six-game match, starting an era of computer dominance at the highest level of chess. In the 2010s, engines of superhuman strength became accessible for free on a number of PC and mobile platforms, and free engine analysis became a commonplace feature on internet chess servers. An adverse effect of the easy availability of engine analysis on hand-held devices and personal computers has been the rise of computer cheating, which has grown to be a major concern in both over-the-board and online chess.[106] In 2017, AlphaZero – a neural network also capable of playing shogi and Go – was introduced. Since then, many chess engines based on neural network evaluation have been written, the best of which have surpassed the traditional "brute-force" engines. AlphaZero also introduced many novel ideas and ways of playing the game, which affected the style of play at the top level.[107]

As endgame tablebases developed, they began to provide perfect play in endgame positions in which the game-theoretical outcome was previously unknown, such as positions with king, queen and pawn against king and queen. In 1991, Lewis Stiller published a tablebase for select six-piece endgames,[108][109] and by 2005, following the publication of Nalimov tablebases, all six-piece endgame positions were solved. In 2012, Lomonosov tablebases were published which solved all seven-piece endgame positions.[110] Use of tablebases enhances the performance of chess engines by providing definitive results in some branches of analysis.

Technological progress made in the 1990s and the 21st century has influenced the way that chess is studied at all levels, as well as the state of chess as a spectator sport.

Previously, preparation at the professional level required an extensive chess library and several subscriptions to publications such as Chess Informant to keep up with opening developments and study opponents' games. Today, preparation at the professional level involves the use of databases containing millions of games, and engines to analyze different opening variations and prepare novelties.[111] A number of online learning resources are also available for players of all levels, such as online courses, tactics trainers, and video lessons.[112]

Since the late 1990s, it has been possible to follow major international chess events online, the players' moves being relayed in real time. Sensory boards have been developed to enable automatic transmission of moves. Chess players will frequently run engines while watching these games, allowing them to quickly identify mistakes by the players and spot tactical opportunities. While in the past the moves have been relayed live, today chess organizers will often impose a half-hour delay as an anti-cheating measure. In the mid-to-late 2010s – and especially following the 2020 online boom – it became commonplace for supergrandmasters, such as Hikaru Nakamura and Magnus Carlsen, to livestream chess content on platforms such as Twitch.[113][114] Also following the boom, online chess started being viewed as an e-sport, with e-sport teams signing chess players for the first time in 2020.[115]

Growth

Organized chess even for young children has become common. FIDE holds world championships for age levels down to 8 years old. The largest tournaments, in number of players, are those held for children.[116]

The number of grandmasters and other chess professionals has also grown in the modern era. Kenneth Regan and Guy Haworth conducted research involving comparison of move choices by players of different levels and from different periods with the analysis of strong chess engines; they concluded that the increase in the number of grandmasters and higher Elo ratings of the top players reflect an actual increase in the average standard of play, rather than "rating inflation" or "title inflation".[117]

Professional chess

In 1993, Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short broke ties with FIDE to organize their own match for the title and formed a competing Professional Chess Association (PCA). From then until 2006, there were two simultaneous World Championships and respective World Champions: the PCA or "classical" champions extending the Steinitzian tradition in which the current champion plays a challenger in a series of games, and the other following FIDE's new format of many players competing in a large knockout tournament to determine the champion. Kasparov lost his PCA title in 2000 to Vladimir Kramnik of Russia.[118] Due to the complicated state of world chess politics and difficulties obtaining commercial sponsorships, Kasparov was never able to challenge for the title again. Despite this, he continued to dominate in top level tournaments and remained the world's highest rated player until his retirement from competitive chess in 2005.

The World Chess Championship 2006, in which Kramnik beat the FIDE World Champion Veselin Topalov, reunified the titles and made Kramnik the undisputed World Chess Champion.[119] In September 2007, he lost the title to Viswanathan Anand of India, who won the championship tournament in Mexico City. Anand defended his title in the revenge match of 2008,[120] 2010 and 2012. In 2013, Magnus Carlsen of Norway beat Anand in the 2013 World Chess Championship.[121] He defended his title 4 times since then and is the reigning world champion.