The Science of Chess Patterns

Explore the Science of Chess UnderstandingPeople improve at chess through learning and understanding patterns.

Examples of Patterns:

- French defense pawn structure

- Good knight vs bad bishop

- Backward pawns

- Knight manoeuvers to outposts

- Pawn breaks

- Bxh7 Greek Gift Sacrifice

- Bishop pair is better in open positions

- Knights are better in closed positions

- Exchange sacrifice to control light or dark squares

Learning more chess patterns is what is referred to as 'getting better at chess'. You aim to memorize the patterns implicitly by understanding the concepts. When I say 'memorize' I don't mean trying to remember every time you see a configuration directly (wouldn't be possible as there are so many combinations).

What you should 'memorize' (understand) is the concept. So let's say you have a good knight vs bad bishop:

You might wonder what if your opponent tries to play differently so as to avoid these patterns.

Different non-pattern moves allow you to impose what you know will be beneficial for you as your opponent is not preventing your plans. In the position shown above, it's possible that in the previous moves, the player with the white pieces deliberately traded pieces to reach this winning endgame. If the opponent had ignored the pattern of bad bishop vs good knight, then they would not have opposed this plan, leading to their demise.

If you're a beginning player you will need to focus on avoiding blunders first. Then you can start focusing on tactics training and studying classic annotated games. Tactics training helps develop tactical patterns while annotated games helps develop positional patterns.

The Science

Research on chess thinking has been done over more than a century to assess how chess players utilize their mind to try to find their next move. The psychologist Alfred Binet at the end of the 19th century studied blindfold chess in expert players and concluded that chess knowledge, imagination and memory were the factors involved in blindfold chess. Binet originally thought that superior visual memory was responsible for blindfold chess skill. He discovered that conceptual chess understanding played a larger role. Henri Bergson elaborated on Binet's results, bringing the idea of 'dynamic schemas' into existence. Dynamic schemas refers to the abstract ideas or goals that can be implemented in a chess position.

A drawing done by one of the chess experts in Binet's study. The drawing shows the nature of representation of a chess position in the mind of a blindfold player. It is not a concrete image but a schematic understanding of the force of the pieces. From Thought and Choice in Chess (de Groot, p. 4).

Adriaan de Groot was a psychologist and chess master who wrote about and studied the thought process in chess during the mid 20th century. de Groot described how the character of a position was formed very rapidly by strong players who could retain and discuss how to proceed in a position without seeing the board after having only seen the board previously for less than 20 seconds. de Groot also found that stronger players were able to remember chess positions more accurately compared to weaker players after looking at the position for only a few seconds.

de Groot discussed Binet's work and pointed out that the relation between chess skill and blindfold ability was not investigated. He also stated the Binet was influenced by the understanding of his time, where imageless thought was not yet accepted due to the philosophy of associationism which viewed thoughts as simply a series of associations between words and images with no real abstract thought operation taking place. de Groot felt that Binet did not fully come to terms with how positions in blindfold chess are 'known' conceptually as opposed to 'imagined' visually. Binet also lacked chess knowledge which hampered interpretation of the explanations of the experts he studied. de Groot nevertheless stated that "one can have nothing but admiration for the results he achieved". de Groot investigated chess thinking under the framework of Otto Selz who viewed thinking as a chain of operations performed in order to achieve a goal, in contrast to associationism.

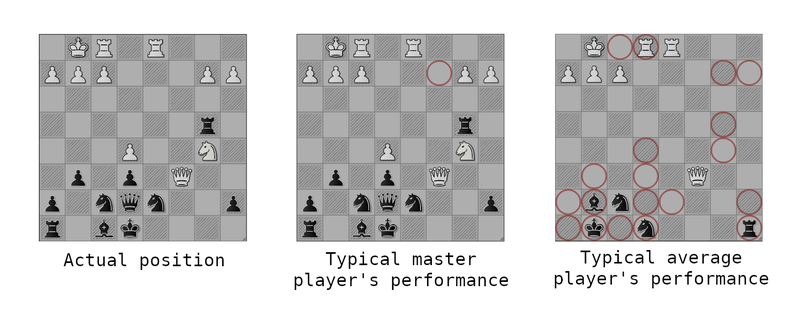

Hearst (1972) had chess players reconstruct positions after only looking at them for 5 seconds. Errors are shown in red.

In 1973, Chase and Simon studied three players (an expert, a Class A player and a beginner) to see how they recalled chess positions. Their results showed that the ability to remember chess positions increased with chess skill. Also, the ability to remember chess positions with randomly placed pieces was not correlated with skill. This study only had three participants, but the results were replicated in later studies. This demonstrates that superior memory in chess is a product of chess knowledge as opposed to superior visual memory in general.

Chase and Simon proposed a model of 'chunking' where chunks were collections of pieces (a fianchettoed kingside castle could be a chunk). Stronger players could remember the positions much more accurately because previously seen chunks were stored in long term memory and stronger players had a larger 'database' of chunks to work with. This implied that the ability to remember chess positions would be dependent on short term memory which would hold the chunks temporarily.

Gobet and Simon (1996, a&b) discussed criticisms of the chunking model, pointing out that contextual information such as what moves came previously helped to improve memory performance which implies that chunks are not the only relevant factor. A focus on chunks in short term memory also didn't mesh with the fact that blindfold players could remember many boards at a time. Gobet and Simon proposed instead a 'template' model. A template is a larger collection of pieces stored in long term memory. For example the King's Indian Defense pawn structure is a basic example of a template. The templates also have 'slots' where the chunks can fit in. The stronger the player the more templates they know. This increases the role of long term memory in chess understanding which explains the fact that their study (1996b) found that stronger players remembered more pieces across multiple boards than the chunking model would predict.

Connors (2011) discussed how the depth of calculation between Grandmasters and masters/strong club players was not significantly different, demonstrating how pattern recognition plays a larger role in chess strength compared to the amount of calculation. More patterns allows more possibility of finding good moves. As it is impossible to calculate every variation this means that using pattern recognition to come up with good candidate moves are what allows a greater level of chess ability.

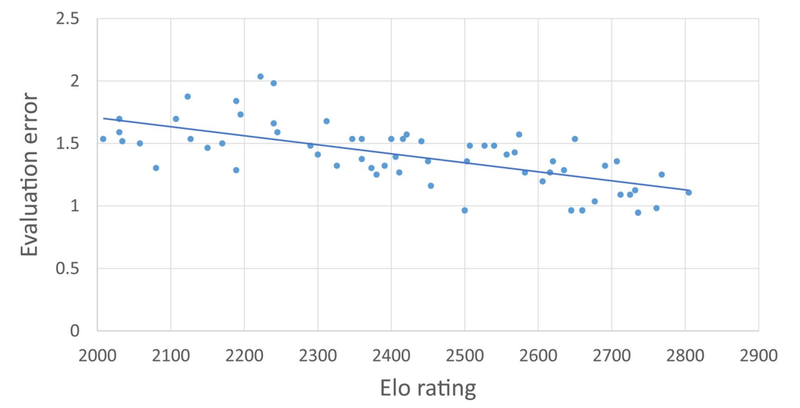

Chassy et al. (2023) got a range of players to evaluate a position after looking at it for only 5 seconds. The results show that the evaluations got more accurate as skill increased. This shows how pattern recognition plays a large role in chess strength as the players did not have time to engage in calculations and had to rely on intuition.

In the final analysis, we can say that if you want to improve your chess you need to understand more patterns.

This explains why computer analysis in the void never really helped anyone get better. You don't really learn new patterns. The computer can tell you the best move, but you need to understand the underlying pattern behind it (in human terms). That is why studying classic games is necessary. Classic games are simpler which can help show the patterns more clearly. You should study annotated games collections by masters of the past. The more games you study, the more patterns you learn. Doing tactic puzzles will also help you recognize more tactical patterns.

Clearly learning patterns is what separates the wheat from the chaff, the amateurs from the masters.

If you want real chess improvement then learning new patterns is the way.

Sources

- Hearst, E. 1972. Psychology across the chessboard. In Readings in Psychology Today, 2nd ed. Albany, N.Y..: Delmar Publishers, CRM Books.

- Perception in Chess, Chase and Simon (1973)

- Thought and Choice in Chess 2nd. Ed (1978), de Groot

- Expert Chess Memory: Revisiting the Chunking Hypothesis, Gobet and Simon (1996a)

- Templates in Chess Memory: A Mechanism for Recalling Several Boards, Gobet and Simon (1996b)

- Expertise in Complex Decision Making: The Role of Search in Chess 70 Years After de Groot, Connors, Burns, and Campitelli (2011)

- Intuition in chess: a study with world‐class players, Chassy, Lahaye, Didierjean and Gobet (2023)

You may also like

RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000Daniel Naroditsky: The Legend

Remembering one of the icons of the modern era. RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000Fischer vs Spassky: The Rivalry (Part 3: 1973-2008)

Explore one of the Greatest Rivalries in the History of Chess CM HGabor

CM HGaborEffective training methods - doing tactics

My previous post was about chess training in general. We will dive into the details now. So, what yo… thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. FM MattyDPerrine

FM MattyDPerrineWhy Masters Crush Lower-Rated Players (and You Struggle)

Hint: The secret isn’t a high ceiling HollowLeaf

HollowLeaf