This is my face.

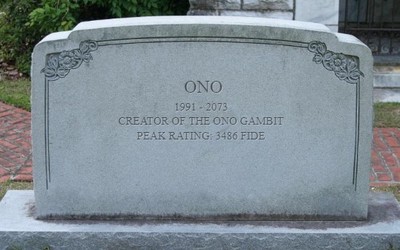

I Don't Speak Chess

I caused mass confusion in my local farm shop by attempting to order 400 metres of butter.What I was actually trying to order was 400 metres of water piping.

I think I’m putting in a world-class irrigation system, and the farm shop guy thinks I’m trying to bake the world's largest cake. Embarrassing.

But what does a Scottish man mixing up the words 'mantequilla' and 'manguera' in his first few months in Spain have to do with chess?

Well, when I first moved to the Asturian mountains in Northern Spain, I thought learning Spanish might be a good idea.

I started out by hearing Spanish words (those were pretty easy to come by because I was in Spain). My brain would then hear these Spanish words and translate them in my head into English. Then my brain thought of a reply in English, translated that back into Spanish and then my mouth tried to pronounce the words with varying degrees of success.

This is not a very efficient way to communicate.

But I also feel like as adults this is how we play and learn chess to begin with.

(Are you also learning chess and would you like support? As a chess coach specialing in Adult Improvers, I offer a free 60-minute trial lesson which you can book here.)

There was a language barrier between me and my Spanish friends just as there was between me and my titled chess friends (or chess authors I believed were my friends).

Sometimes, the meaning of whatever I and my Spanish friends were trying to say to each other was simply lost and we’d just have to shrug, laugh and move on.

I never blamed my Spanish friends for this. I took responsibility for the language barrier myself, and I tried to get better at speaking Spanish to resolve the problem.

Oddly, I did blame chess authors for the exact same issue.

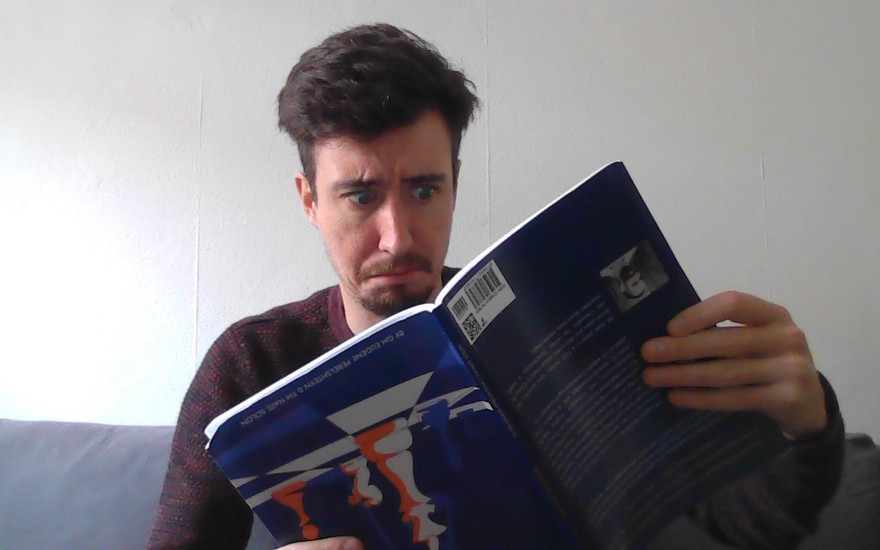

Man Reviews All Chess Books - 1.5/5

When I first tried to read a chess book I was furious.

I was so annoyed at these Grandmasters and their hieroglyphic-looking tombs, all letters and numbers, making no sense.

I felt like I was trying to find out what time it was, and when I asked the author they smirked and handed me a sundial.

I don’t want to have to go through all these variations and work out what you mean, just tell me, I thought. Tell me in words. Is that too much to ask? Just say it’s two o’clock in the afternoon, and keep your medieval time contraption, you weirdo.

Except, that is not entirely fair to the titled chess authors of this world.

That was kind of like getting annoyed at my Spanish friends for not ‘just’ speaking English, simply because I didn’t speak Spanish (yet).

Fairly unreasonable.

The great chess authors of this world weren’t being deliberately vague. They were just speaking a different language to me.

One that I didn’t understand, yet. And it was perhaps (fine, it was definitely) my own sense of entitlement that made me believe all chess books should be specifically written for me - a non-native speaker.

I now realise that many authors weren’t failing to speak my language - they weren’t trying to.

Many chess books are written by native speakers for native speakers.

And that’s okay. An example:

Take a look at this theoretical endgame position.

A chess author might write and after:

Ra8+ Kd7, Ra7+ Kd6, Ra6+ Kc7, Rc7+ Kd8, draw.

I needed words here. I needed to translate the chess into English.

I needed someone to explain why it was a draw. I needed to have this explained to me in words, a lot of words. I need this explained to me like I was six years old. I needed someone to say:

There are three squares of separation between the rook and the pawn (this is called effective checking distance) therefore, the black rook can check the white king endlessly on the a-file BECAUSE if the white king tries to approach the rook via c7 and attack it, they will lose the pawn to a skewer.

If the king tries to approach the rook via c8 or c6, we just give a check on the a-file and then either the king goes back or (after Kb7 trying to attack the rook again) we go either in front of or behind the pawn and pick it up next turn.

The white king can’t run away from the checks because there are only two squares the white king can hide on the entire board - g1 and h1 and if it goes over there, then black's rook and king will collect the pawn with approximately a million turns to spare, because white's rook is one defender and black will have two attackers - the rook and the king.

Ahhh, but what if the white rook checks my king after I go behind or in front of the pawn, I hear you ask? No need to panic, just shuffle back and forth between g7 and f7 forever singing the Cha Cha Cha song from this year's Eurovision song contest final.

So it is a draw because the white king cannot escape the checks from the black rook, and if it does escape them, white will lose their pawn.

Now, the endgame author who wrote the variation followed by the word “draw”, might read my lengthy English explanation and then look at their variation and think: but I just said that! Why on earth would I need to write the same thing twice?

And that would be a fair point.

Adult Improver Chess Coaching | Free Trial Lesson | Support the Blog on Patreon

Developing Partial Fluency

The issue for me, to begin with, was that I needed to translate chess into English.

Variations into words. And then words back into chess.

And I still do for the most part. I guess if you picked the game up as a kid or can play this game at a really high level, there is no need to translate chess into English or whatever language you speak.

And I hope that as I get better at chess, I won’t need to translate things at all. Maybe I’ll still need to read it very slowly, maybe I’ll stumble over a word or two.

But hopefully, no one will think I’m the mental guy walking around the village with a 'pear' tied to a bit of string.

That’s right Josefina, I took my 'dog' for a walk. I’m not a lunatic. And I’m baffled that you didn’t understand that from context.

Who takes a pear for a walk?

“Ahhh, es perrrrrro. No es pero.”

Close enough Josefina, give me a break. I’m still learning.

Abandoning Chess Books

The process of translation slows me down a lot when it comes to studying chess books.

It's one of the reasons I prefer to learn from videos.

There, the authors have little choice but to translate the chess into words for us mere mortals anyway.

But I confess, I do love a chess book and a nice hot cup of tea on a rainy Sunday afternoon.

So I have compiled a list for you to download here of my favourite chess books that contain nice Adult-Improver-friendly, wordy and variation-lite explanations of chess concepts.

Because after some thorough searching, I have found some gems - books I really felt I could understand. And if you’re an Adult Improver like me, I think this book recommendation list could be really useful for you, too.

Reading Above Your Level

I want to talk about how I have been able to extract value from the types of chess books that weren’t written “in my language” (or at my level).

Because I don’t think I use all chess books in the way they were intended to be used.

Take IM Jeremy Silman’s How to Reassess Your Chess. Great book. Handy to have around if you're short of a weapon in a zombie apocalypse too. It’s a hefty tomb.

So have I read it? Sort of. The author, IM Jeremy Silman would probably say I haven’t.

The thing is, as an Adult Improver I didn’t know what any of the imbalances were. Rather than spending a couple of decades going through every game and variation in the book, instead, I read the introduction to each chapter.

In those introductions, Silman told me what each imbalance was and a little bit about it. That was enough for me to start experimenting with these imbalances in my games.

I didn’t need to play through every example of how to open a closed position with the bishops. In a game, if I had the bishops, I just played at trying to open the position and experimented until the concept started to make a bit more sense to me.

I think as adults who are new to chess we can underestimate the value of these guiding bits of information. And for me, it is better to gather as many bits as I can, rather than only a few bits with many examples.

I mean, if someone tells you rooks belong on open files - that is useful. If they tell you to try and avoid moving the same piece twice in the opening because you will fall behind in development - useful. Don’t put your knights on the edge of the board because they control less squares - useful.

These are all bits of advice you can follow without actually yet understanding them. Comprehension will come later through experimentation with these guiding bits of information.

Even if you don’t know why yet, the information in itself is useful and the why will come by playing with these concepts.

As Adult Improvers who are (relatively) new to chess, we are often not reading these books to deepen our understanding of concepts - we are reading about these concepts for the first time.

I think many of the chess books we Adult Improvers read, were originally written to deepen the native chess speakers' understanding of concepts - and not to introduce these concepts as new ideas. And a lot of the time all we need is knowledge that the idea itself exists to get started.

I Chess Speak Now

It was more effective for me to have a larger vocabulary and be able to communicate more in Spanish than it was to be able to speak a few phrases grammatically perfectly. And I think the same is true of chess.

First, collect many vocabularies and then work hard to found the good tense and order words to make sense.

In the beginning, it’ll sound odd to native speakers, but at least you can talk.

And once you can communicate (even poorly), you can start to practise and slowly improve.

Until the day that you not only can get your point across, but can do it with decent grammar, too.

First though, you have to get over your embarrassment and gracefully stumble through this phase.

You’ll still be understood, and that is better than not being able to speak at all.

So start somewhere, anywhere (like my 10 favourite books for Adult Improvers) and practise your heart out.

Even if you pick up just one thing from each book, you've learnt ten new things that will make you a better chess player.

And I'm sure you and I agree, that's what it's all about in the end.

Thanks to Patrons of TheOnoZone: Ben Johnson, Michael Shpizner, Dawn Lawson, Mikey W, Alan M, Dan Bock, Jose C, Marcus Buffet, Andrew M, Ché Martin, Stefan K, Ross W, Bowie, Gregory C, Karen W, Michael G, and NoSir100.

Enjoying my chess content? Please consider supporting me and my writing + get access to exclusive perks and live Zoom events with special chess guests by becoming a Patron.

You can receive news about my future blog posts and my other chess stuff by subscribing to my newsletter. You can also grab your free Chess Study Plan Template here and here you can download the Wordy Chess Book List that I created for this blog post.

And if you're an Adult Improver looking for someone to help translate chess into English for you (and get continuous support on your chess journey), you're welcome to book a free trial lesson with me.

In 60 minutes, I’ll give you specific pointers on the next steps for your chess improvement, based on 3 of your actual games. I don’t do one-size-fits-all approaches, you’ll get a personalised chess lesson prepared just for you, for no cost at all.

You can also read more about my chess coaching for Adult Improvers rated <1100 FIDE (<1600 Lichess rapid/classical, <1300 chess.com rapid).

Finally, if you want to get in touch with me, please do so on your medium of choice:

I have a contact form on my website www.theonozone.com, you can hit me up on Twitter, send me an email at info@theonozone.com, or message me right here on Lichess.

More blog posts by TheOnoZone

Adult Chess Clock

I used to say that nobody doesn’t have the time for something, they just don’t want to prioritise it.

The Ono Gambit

I am getting older.

Losing Consciousness

It was game over.